Capturing Pandemic-Era Preservation – Archive Your 2020/21 Activities

December 5, 2021

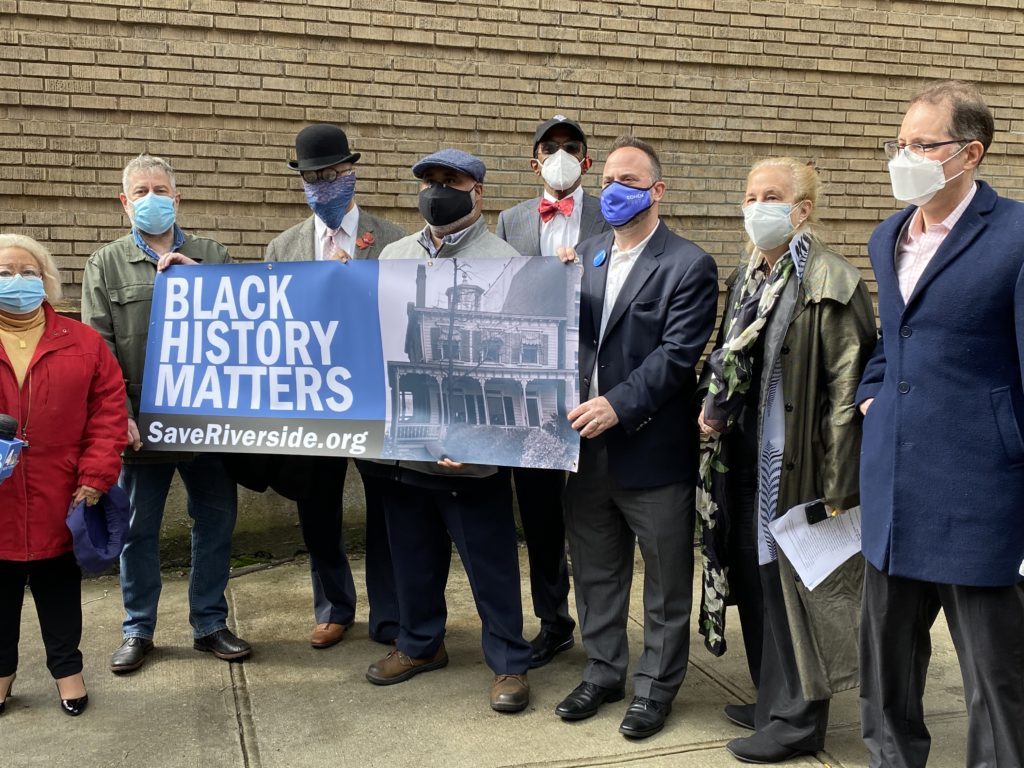

operative. (l-r) Maria Luna, Mitch Mondello, Michael Henry Adams, Corey Ortega, Assembly Member Al Taylor, Dan Cohen, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer,

Manhattan Borough President-elect Mark Levine | Courtesy of Nora Fritsch/Upper Riverside Residents Alliance/Save Riverside

By Brad Vogel, Executive Director

Did you fight for a historic building at risk during the past year and a half? Did you don a mask and take to the streets to oppose senseless demolitions? Did you shift your programming to Zoom to maintain momentum?

If you have taken any action during the global pandemic to protect historic resources, it is time to take the next step: create an archival record of your efforts! Doing so can seem like a major lift amidst the many challenges thrown at beleaguered New Yorkers each day, but it is of utmost importance, as the Archive Project knows full well. Ensuring that a record of preservation activities—even those that did not succeed—exists for the future helps to generate the full story of New York City. Gotham is a place of dynamism, yes, but its greatness also derives from the efforts of those who love and fight like hell for the special, the rare, the classic, and the livable aspects of the city. Someone once called them preservationists.

A good preservationist, of course, is also an archivist. For organizations and individuals engaged in historic preservation, the all too ephemeral advocacy blitzes that emerge on an ad hoc basis in the face of crisis are wont to disappear. So make it a habit to place those printouts, pins, and posters in a titled folder. Or get to know someone who can do that task for you. Save labeled electronic documents, copies of social media posts, and e-blasts in an external hard drive and the cloud, including one or more places where someone might look in a pinch if you are no longer around. Send photos to people who appear in them for their own records.

Those, really, are the baby steps. Here are some additional thoughts on how to take stock of what just happened across the pandemic and make sure the record of your personal or group preservation advocacy work is not lost in the fray. Remember, people in the future will likely be especially intrigued to know what people were doing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Take Stock: Conduct a mini-assessment. Time warped weirdly during the pandemic, so take a moment to build a timeline of your preservation activities during the past two years. Then, use that timeline to locate and review any physical or electronic reminders of those activities.

2. Organize: Get it together! Build a system, no matter how simple, to categorize and make logical what might be a maelstrom of images, emails, and banners. Label things; people and places depicted in a photograph might be obvious to you, but will that hold true for a third party viewer in the future? Err on the side of recording more explanatory information. If you have the need and the means, consider hiring an archival consultant to assist with this step.

3. Safety & Redundancy: Once you have coalesced your own collection, think about how you will keep it from disappearing in the immediate future. Are the papers currently in a room where moisture is a problem? Is your laptop where the protest photos are stored…a decade old and getting shaky? Make copies. Send a duplicate external hard drive to your cousin’s house. Take steps to make sure that your collection is not in immediate danger.

4. Share: Do not hide your story if it is worth sharing. Tell the world! One of the best ways to ensure that preservation stories are not lost is to circulate them widely and let a reassuring redundancy grow in their retelling. If you are part of an organization, consider both internal and external audiences. Employ Creative Commons or other use guidelines as needed. Tag us in your photo on Instagram: @nypap_org.

5. A Long Term Home: Think long term about the collection that represents you and your work as a preservationist during the pandemic. What will happen to it when you are gone? Consider inquiring with a collecting institution (a museum, historical society, archive, or library) about whether it might want to acquire your collection today or at a point in the future. In 2020, multiple pandemic-specific collecting efforts emerged seeking items that helped to tell the story of the pandemic in New York City. Here are just a few of those efforts you may want to consider, as they remain ongoing:

History Responds, New-York Historical Society:

www.nyhistory.org/history-responds

The Great Pandemics Archive:

www.jamiecourville.com/pandemics-timecapsule

Neighborhood Stories — NYC Department of Records & Information Services:

www.archives.nyc/neighborhoodstories

The fact that the pandemic is not yet over is quite apparent as I conclude this piece; I write it while home after a breakthrough case of COVID-19. Thankfully the symptoms have not been severe. But the time in quarantine has made me glance over at a pile of handmade signs, posters, and folders from 2020 that sits near my weatherworn waterfall armoire. The pile, generated in my free time, remains stuck at phase three in the steps I laid out above. I think it may be time to stop typing and go push the pile to phase five so posterity might know what this strange time has been about.