Everything Old is New Again

October 16, 2015 | by Anthony C. Wood, Founder & Chair

Article from the Fall 2015 Newsletter

In the years before the 1965 passage of New York’s Landmarks Law, engaged and increasingly enraged New Yorkers worked through their civic organizations to employ exhibits, tours, plaques, public programs, and special publications to educate and enlist a constituency to advocate for the preservation of New York City’s threatened landmarks and historic neighborhoods. Even the airwaves were activated in 1961 with the first televised documentary on historic preservation in the City. Now, in the midst of the gala celebration of the 50th anniversary of New York City’s Landmarks Law, I have been struck by the fact that these time honored education and advocacy tools, refined, reimagined and often technologically upgraded, are still being used to educate and enlist generations of New Yorkers to the cause of historic preservation.

Certainly, the 50th anniversary celebration has added some exciting new approaches to engaging the public. Everything from marathons in Central Park to banners being flown across the City, from the illumination of the Empire State Building to the ringing of the NASDAQ bell, from preservation advocates looming large on the Jumbotron screen in Times Square to the “Honor Our Past, Imagine Our Future” billboard on the way to Kennedy airport have been employed to get the message out to as many New Yorkers as possible. However, what has fascinated me the most is not the wonderful new media being utilized but the continued embracing and robust deployment of the very tools that helped propel the passage of the Landmarks Law in the first place.

In the 1950s, several modest exhibits were mounted to help draw attention to New York City’s architectural treasures. The 50th anniversary has been celebrated with no less than ten new exhibits. Currently on view and extended through the end of the year is the blockbuster Saving Place: Fifty Years of New York City Landmarks exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York. A virtual smorgasbord of preservation-themed exhibits preceded it. Organizations ranging from the Alice Austen House and the Society of Illustrators to the New York School of Interior Design to the New York Transit Museum celebrated preservation with exhibitions highlighting scenic landmarks, interior landmarks, landmarks of transportation, landmarks the Scots built, lost landmarks, existing landmarks, potential landmarks; landmarks here, there, and everywhere! Those 1950s pre-law exhibits were only seen by a select crowd of a few hundred, today’s exhibits have reached a broad and vast audience of tens of thousands.

Architectural walking tours, inaugurated in New York City by the Municipal Art Society in 1956, have long been a staple of preservation awareness. Thanks to the 50th anniversary, walking tours and bus tours have reached a new level of intensity. Whether a marathon, all-day five borough bus tour of Art Deco treasures or an endless number of exhilarating romps through historic districts large and small, near and far, New Yorkers have gotten up close and personal to their history. Walk on New York!

The 1950s debuted the “Landmarks of New York” plaque program of the New York Community Trust. Thanks in part to the 50th anniversary, the cultural medallion program of the Historic Landmarks Preservation Center has been in high gear mounting medallions on sites linked to figures ranging from the Archive Project’s own favorite, the preservation great Albert S. Bard (grandfather of our Landmarks Law and subject of an article by yours truly in the latest issue of the Museum of the City of New York’s City Courant) to Bella Abzug, John Lindsay, and Dr. Jonas Salk.

As a young preservationist (yes, that was decades ago) I questioned the value of these old-fashioned preservation activities. Weren’t walking tours and plaques examples of 1950s preservation? Hadn’t we progressed beyond that? Shouldn’t our focus be on hard-edge preservation policy issues and the politics of preservation? Do exhibits, walking tours, documentaries, medallions, and the vast array of public programs that have accompanied them actually save buildings? Do they really help move the needle for the cause of historic preservation?

Today I have to answer that question with a resounding “yes.” Not only is constant vigilance essential for preservation, so too is the constant engagement of the public, one generation after another. These familiar tools are indeed time honored. We keep using them—revised, inspired, and updated by what we’ve learned by new technologies—because they truly engage people. It is that personal engagement that transforms a passive New Yorker into a passionate preservationist.

Another deeply rooted and cherished activity that has served preservation well is the presentation of awards. By recognizing remarkable people whose accomplishments represent their values and missions, preservation and civic organizations put a public spotlight on their own efforts. In the 1940s and 1950s the great preservation figures were routinely honored with medals and awards, usually presented at banquets. In 1951 George McAneny was presented with the Municipal Art Society’s Presidents’ Medal. Among those sitting on the dais was Albert Bard. The banquet featured “Hearts of Celery, Queen Olives, Gumbo Creole, Breast of Rhode Island Duckling stuffed with bread and apples, watercress, asparagus vinaigrette, Baba au Rhum, and demi tasse.” In 1952 the Award was given to Bard.

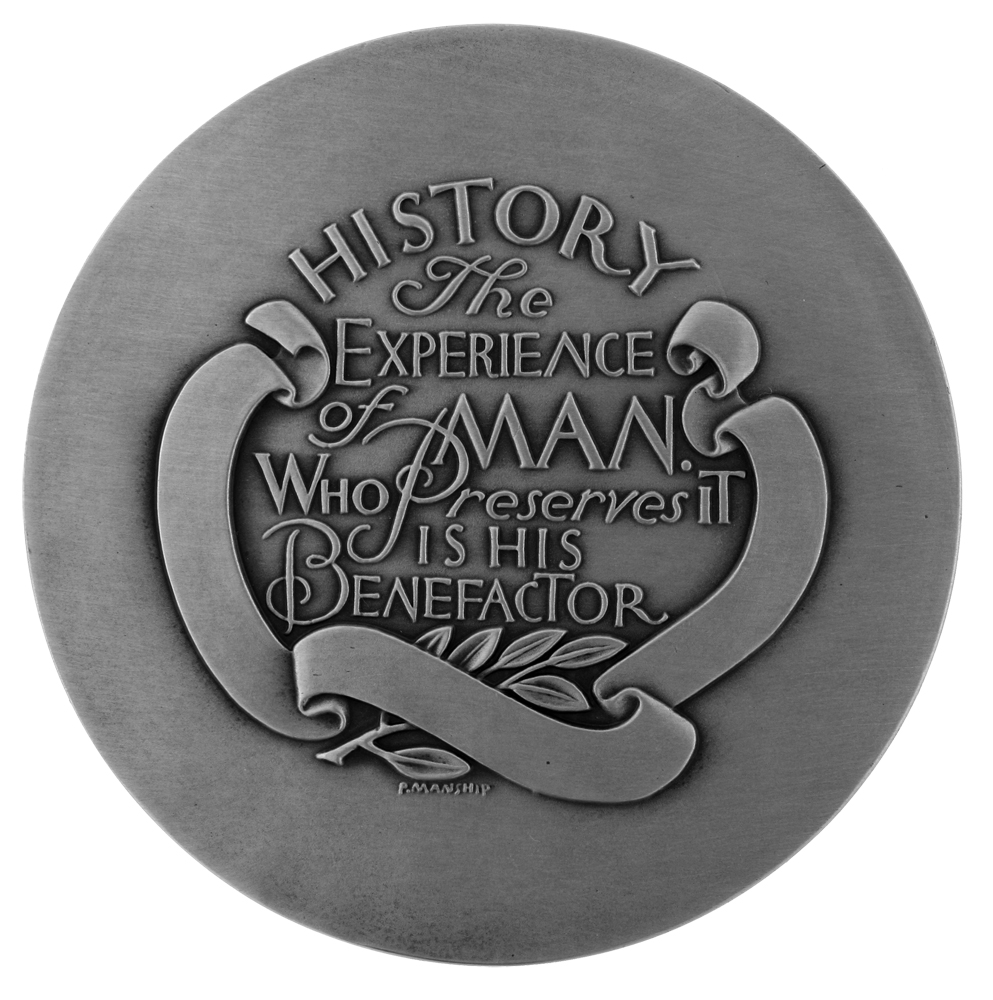

My favorite of all the preservation medals is the stunning George McAneny Medal, established in 1945 and designed by Paul Manship. Awarded for years by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society and named for and made possible by its longtime president, it recognized distinguished service to the cause of preservation. Over the years it went to such nationally prominent preservation figures as Major General Ulysses Simpson Grant, III, Henry Francis du Pont, C.C. Burlingham, H.P. Pell, William Sumner Appleton, and David Finley.

In recent times, sadly but perhaps understandably, awards often seem to be more about elevating an organization’s finances than elevating its mission and values. Yet the power of an award to highlight an organization’s work is as real today as when the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society launched its award in 1945. Inspired by them and the long history of such medals, the New York Preservation Archive Project is having a new preservation medal cast and will be presenting it for the first time this December at our annual Bard Birthday Breakfast Benefit. The Archive Project’s Preservation Award will be presented to individuals whose work exemplifies the preservation, documentation, and celebration of the history of preservation, which is the focus of our work. The award will be given out periodically—when it is truly deserved.

There is no better time than the 50th anniversary of the Landmarks Law to inaugurate this award and no more deserving first recipient than Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel. Over the decades she has played a singular and decisive role in helping preservationists remember and honor their own history. Personally, I remember meeting with her to discuss the planning of the 15th anniversary celebration of the Landmarks Law!

Does preservation need another award? Another exhibit? Another walking tour? Another plaque? Another documentary? Even if the wrecking ball stopped swinging tomorrow, the answer would still be an emphatic “yes.” All these efforts are essential to ensuring that preservation is not taken for granted and that the inspiring, instructive, and inspirational history of how New York City has preserved its landmarks and historic neighborhoods is not lost to future generations. The methods may be old but through reinvention and fresh audiences they are new again. For as musician Peter Allen’s wonderful lyrics sing out:

“… don’t throw the past away

You might need it some other rainy day

Dreams can come true again

When everything old is new again”