Robert Low

Also known as Bob Low

Robert Low was a New York City Councilman who, along with Seymour Boyers and Richard S. Aldrich, introduced the landmarks preservation bill which would become the New York City Landmarks Law.

Robert Low, a New York lawyer, politician, and supporter of preservation, was born in 1918. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Stanford University, and received his law degree from George Washington University. At the age of 25, he became one of the youngest lieutenant commanders ever to serve in the Navy. As a veteran, he received nine battle stars in recognition of his Navy career. He and his wife Frances resided in Manhattan’s “Silk Stockings District,” at 527 East 84th Street.1

Low began his work in the arena of politics when he served as executive assistant to Henry M. Jackson of the House of Representatives. He also handled Congressional Relations for the State Department. Subsequently, he served as a legislative assistant to Senator Lehman, and later as assistant to Mayor Wagner. Low began his own political career when he became a New York City Councilman.

As a city councilman, he headed the Committee on Buildings, and did a great deal of work in the housing field. He also served as chairman of a special committee responsible for investigating air pollution. Low’s district covered the Upper East Side of Manhattan and included East Harlem, a part of Central Harlem, and the eastern half of Yorkville down to 59th Street.2

In 1964 he turned down the Democratic Party’s offer as nominee for Representative in the 17th Congressional District, noting that he would “decline because of the importance of the work to be done in the City Council.” The Democratic Party thought Low represented their best chance at defeating John V. Lindsay, a Republican, who was a “potent vote getter.”3 However, in December of 1965, when Lindsay announced that he would vacate his office on January 1 to assume position as Mayor, Low experienced a change of heart, and opted to enter the race. His platform boasted his “unique combination of experience in Washington and New York, that would enable him to serve effectively as Congressman from the moment I take the oath of office.”4

As a public leader, Low was known to “masquerade in various roles to learn firsthand about job and living conditions,” in New York. For instance, in 1967, he moonlighted as a taxi driver in order to learn some of the problems of the cab industry.5 Then, Low disguised himself as a struggling writer and moved into a slum in East Harlem for one week, in order to truly experience the conditions, in the hope of instituting real improvements.6

New York City Councilman, 1961

Chairman, Special Committee Investigating Air Pollution

Chairman, Committee on Buildings

Throughout his political career, Robert Low presented himself as an important ally to preservation interests in New York City. In 1960, the Greenwich Village community expressed their desire to "bottle up the Village" against indiscriminate construction. Arnold Bergier, a sculptor, who represented the interests of the Greenwich Village community, proposed implementing the Bard Act in the Village. He posited that the new law should be appended to the city zoning code, in order to make it applicable to specific neighborhoods. While working as assistant to Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Robert Low acted as an influential liaison between Bergier and Mayor Wagner regarding this matter.7

Low confirmed his status as a friend to preservation interests when he opposed Robert Moses. In 1964, the City Council voted to permit the World’s Fair Corporation, under the leadership of developer Robert Moses, to extend its lease of the fairgrounds for two years after the fair ended. Moses proposed a plan to use the profits from the fair to build parks on the fairgrounds. Under Moses's plan, Flushing Meadow Park would be developed with a connection to Little Neck Bay, creating a seven-mile long stretch of parkland. Low insisted that "a man who is not a city official," meaning Robert Moses, "should not be given the authority to build parks." Low predicted that the proposed park would be done "without public bidding" and that the park would cost citizens more than $23 million. Several Queens Councilmen, including Joseph Modugno, Edward L. Sadowsky, and Seymour Boyers, however, disagreed with Low’s position.8

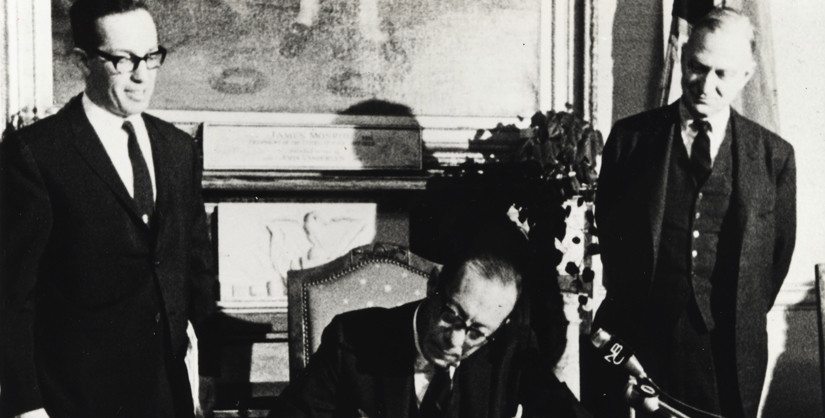

Low made perhaps his greatest contribution to preservation on December 3, 1964, when he, along with Seymour Boyers and Richard S. Aldrich, introduced the bipartisan Landmarks Legislation Bill at a public hearing before the City Council. This important legislation eventually came through the Committee and was passed into law.9

- Oral Histories with Robert Low and Seymour Boyers

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Clayton Knowles, “Low Enters Race for Lindsay’s Seat in Congress,” The New York Times, 6 December 1965.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thomas P. Ronan, “Low Won’t Enter Race for House,” The New York Times, 21 March 1964.

- Val Adams, “Councilman Low is Moonlighting as Taxi Driver,” The New York Times, 18 September 1967.

- “Robert A. Low: Obituary,” The New York Times, 23 February 2014.

- ”Bottle Up the Village,” Villager, 4 August 1960.

- ”Council Supports Fair’s Park Plan,” The New York Times, 25 March 1964.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 338.