The Year of the Bard!

May 11, 2017 | by Anthony C. Wood, Founder & Chair

Article from the Spring 2017 Newsletter

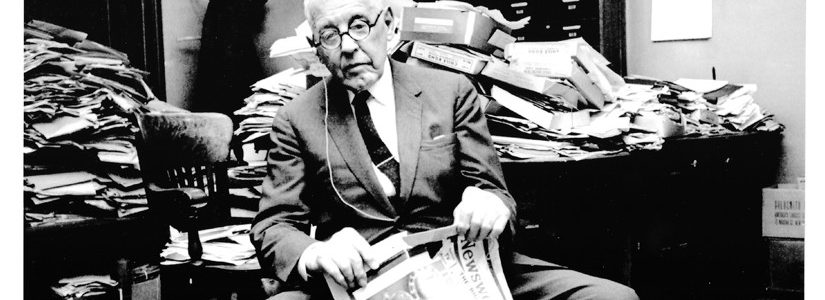

Do not let the absence of a Hallmark greeting card in your mailbox or the failure of the U.S. Postal Service to issue a commemorative stamp in any way dampen your joyous celebration of this special anniversary year. Of course, dear readers, I am referring to the sesquicentennial of the birth of Albert Sprague Bard (December 19, 1866-March 25, 1963), the “grandfather” of New York City’s Landmarks Law. Though Bard’s importance has yet to penetrate the larger national consciousness, his civic achievements are being appreciated by more and more New Yorkers. In fact, with so many other important historic New York City civic figures remaining unappreciated, why do we continue to make such a fuss over Albert Bard?

In a sense, Bard has become the poster child for the ongoing work of the New York Preservation Archive Project. He is the archetype of the virtually forgotten yet hugely important preservationists whose stories the Archive Project seeks to rediscover and share. Bard’s story would not be known if his papers had not been saved. Their loving preservation by the wife of the man Bard regarded as his adopted son, who for months after Bard’s death regularly traveled to New York City from upstate to go through his papers, continues to be a source of inspiration. This example helps to motivate us in our work of raising the awareness of the preservation community of the importance of stewarding the personal papers, organizational documents, and ephemera that can tell the story of preservation in New York City.

Bard and his story make the case for why the Archive Project does what it does. His life and work inform, inspire, and instruct today’s preservationists and those preservationists who follow us. The Archive Project documents, preserves, and celebrates preservation’s history because whether it is the story of Albert Bard, Margot Gayle, Brendan Gill, Joan Maynard, or Dorothy Miner, it is a part of the intellectual capital of the preservation movement. Much can be learned from those who have come before us. Their lives offer us context, continuity, and courage.

Since it is the Year of the Bard, it is fitting to call out some of the lessons to be learned from his life and work. Jim Collins, the business consulting guru, and his co-author, Jerry Porras, coined the term BHAG (Big Hairy Audacious Goal) in their book, Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Bard’s BHAG was his belief that government had the right to regulate private property on aesthetic grounds. When Bard proposed this idea in 1913 it was truly visionary and as history would show, it was years ahead of established thinking. Bard, like a dog with a bone, would not let go of his idea and over the decades would seek every opportunity to advance it. With time, the unconventional can become the conventional. Game changing ideas take years to come to fruition. The willingness to think big and not be limited by conventional wisdom is one of many lessons to be learned from Bard. Like Bard, preservationists need vision.

Having a big idea is not enough if you do not have the staying power to see it through to reality. Bard’s picture should appear in the dictionary under the definition of perseverance. Bard first floated his BHAG in 1913. When he proposed this idea at the 1915 New York State Constitutional Convention it sank like a lead balloon. He tried again in 1938. In the 1940s and into the 1950s he continued to seek a legal basis for regulating private property on aesthetic grounds. In 1954, in response to a threat to Grand Central Terminal, he tried once again, drafting a piece of legislation that when ultimately passed in 1956 would become known as the Bard Act. It gave New York City the authority Bard had been seeking for over 40 years: the power to regulate on aesthetic grounds. But having authority to do something and actually using that authority are two different things. Bard continued to advocate for New York City to use that authority until he died in 1963. If he had held on a little longer, he would have witnessed that authority become a living thing in 1965 with the passage of New York City’s Landmarks Law. Like Bard, preservationists must have perseverance.

Having a vision and relentlessly pursuing it would come to naught if one were just a lone voice in the wilderness. Part of Bard’s success was the result of his decades-long involvement in a cluster of civic organizations. When Bard became part of an organization, it was for the long haul, and he played the long game. Because Bard was simultaneously involved with the Municipal Art Society, the Citizen’s Union, the City Club, and the Fine Arts Federation, and was a close colleague of such civic mavens as George McAneny, C.C. Burlingham, and Robert Weinberg (to name just a few), he could leverage their combined clout to advance his agenda. Bard was an expert at collaboration and coalition building. Like Bard, preservationists must be consummate networkers.

Bard believed some things were so important one had to fight for them even if the odds were stacked against you. Bard was a key figure in the successful battle against Robert Moses to defeat the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge. In a letter about the struggle to his friend Felix Frankfurter, a then-recently appointed Supreme Court Justice, Bard wrote:

“The whole thing is being railroaded through in an outrageous manner. Information is withheld and inquiries are obstructed. Even hearings have not been fairly conducted…Can feeble little folk like me save the city from a serious blunder? I don’t know. It is certainly uphill work.”

Up against as powerful a foe as Robert Moses, and engaged in a battle where facts, figures, and logic were disregarded, Bard fought on. He and his colleagues were willing to endure the cruel barbs of Robert Moses. Like Bard, preservationists must have courage.

Indeed, it took guts for Bard to battle the likes of Robert Moses and to take on other such powerful foes as the national billboard industry. Bard had the intestinal fortitude and the natural instincts to do battle. At one point he wrote to his much more polite colleague in the war against the billboard industry, Elizabeth (Mrs. Walter) Lawton: “I know that I am inclined to shout where you whisper. Thank you for shushing me from time to time. But I also know that a lot of people are deaf, and that the gladiators did not go to afternoon teas in the coliseum.” Not only did Bard have the right personality to engage in battle, he also had incredible strategic instincts. In the ultimately successful decades-long struggle to save Castle Clinton from Moses, Bard and his colleagues perfected preservation strategies still used today: challenge a project at every step of the process, enlist the press, use visualization tools to demonstrate potential impacts, build broad coalitions, employ law suits to buy the time and space needed to triumph, and never give up as long as the landmark is still standing. Like Bard, preservationists must be sophisticated and strategic fighters.

Bard is just one source of inspiration. Whether one looks to such early civic leaders and preservationists as Andrew Haswell Green and George McAneny, or leaps decades forward to the likes of Shirley Hayes, Ray Rubinow, Henry Hope Reed, and Ruth Wittenberg, or looks to more recent preservationists such as the Ortners, Georgia Delano, Teri Slater, and Fred Papert, there is much to be learned from all their stories. Preservationists today should feel a powerful sense of pride in being part of such a long, empowering, and honorable civic tradition.

Celebrating Bard is in essence a reminder to study, salute, and celebrate all our preservation forebearers. Today, more than ever, preservation needs visionary leaders with the perseverance, networking abilities, courage, and fighting spirit to take on the challenges facing New York City. Learning from the past can only increase preservation’s chances of success in the future.

Isn’t it time you made your plans to celebrate the Year of the Bard? What better way to do so than by capturing the story of your favorite preservationist through an oral history interview, putting in place plans to safeguard your own archives, making sure your favorite preservation organization is stewarding their records, and heading off to the next preservation rally? Another modest suggestion: make another (or your first) donation to the New York Preservation Archive Project. Happy Year of the Bard!