Spanish Camp

Also known as Dorothy Day Cottages

Despite efforts to preserve this unique collection of bungalows, one of which was lived in by noted social reformer Dorothy Day, Spanish Camp was demolished in 2001.

The Spanish Camp bungalows were built in 1929 by the Spanish Naturopath Society on the western tip of Staten Island, overlooking the Raritan Bay.1 The camp served as a summer respite for Spanish immigrant workers in New York City who emphasized a communal, naturalistic lifestyle. The cottages originated as temporary canvas tents with a central communal area containing a meeting hall, kitchen, latrines, and showers. Many events took place in the central hall including musical performances, Labor Day festivals, and flamenco dancing exhibitions.

In the 1940s the cottages transformed into more permanent bungalows as individuals began to live there year round.2 Over the next 70 years the camp became a haven for Spanish workers and immigrants. Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, moved to a cottage close by the Spanish Camp in the spring of 1924.3 Prior to her move, she had lived a Bohemian lifestyle in Greenwich Village as a socialist journalist. The cottage and serenity of the Spanish Camp area provided the environment for Dorothy’s religious conversion to Catholicism in the 1920s, despite the admonition of her socialist compatriots who felt religion served as “an opiate of the people.”4

Her conversion motivated Dorothy to return back to Manhattan in order to pursue a mission that synthesized both the Catholic and Labor movements. In 1933, she founded the Catholic Worker Movement with French philosopher, Peter Maurin.5 Dorothy and Peter dedicated years to promoting better treatment of the poor by setting up camps, homeless shelters, and distributing food to the needy. Peter Maurin encouraged Dorothy to start The Catholic Worker, a newspaper focused on the social teachings of the movement that was distributed in Union Square. The headquarters for the paper was located in a tenement house in the Lower East Side. The house soon became a shelter for the poor and homeless.

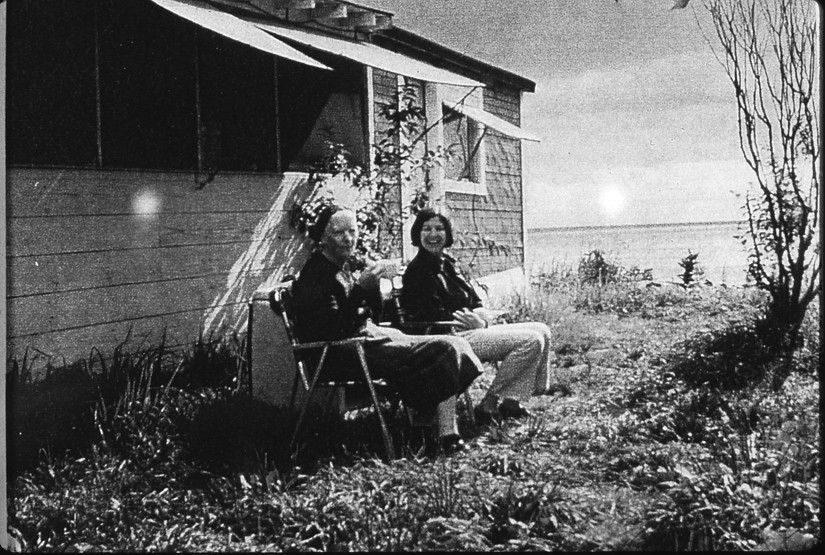

In 1972, weary from her relentless battles, Dorothy once again sought the solitude of the Raritan Bay and returned to Staten Island in order to reflect on her life’s journey. The Catholic Worker purchased three cottages from the Spanish Naturopath Society.6 Dorothy spent the last eight years of her life in the peaceful serene setting and communal air that the Spanish Camp had inculcated over the years. She died in 1980 at the age of 83. The Vatican is now reviewing her candidacy for Sainthood.7

In 1997, John DiScala purchased the property from the Spanish Camp and the Catholic Worker Society and proposed to build 37 new homes.8 Preservationists quickly worked to save the camp by proposing a historic district to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC).9 Furthermore, a not-for-profit organization, Friends of the Dorothy Day Cottages, was founded in order to maintain the history and physical fabric of the cottages. The LPC reached a non-binding agreement with the developer to preserve a handful of the cottages, however they were not quick enough to designate the buildings.10 In a highly tense battle between the developer and preservation groups, the LPC failed to act quickly enough: DiScala had obtained a permit to demolish the Dorothy Day Cottages. After a City investigation, it was discovered that the demolition permit had been forged. After the company paid a $2,500 fine, the proposed development was put to a halt.11 Today the only vestiges that remain of the Dorothy Day Cottages and the Spanish Camp bungalows is a vacant, overgrown lot.12

The Spanish Camp area and the Dorothy Day Cottages were never designated New York City Landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and were demolished.

1997: Developer John DiScala purchases the land of the Spanish Camp from descendants of the founders of the Spanish Naturopath Society, in addition to the three cottages previously owned by The Catholic Worker

July 31, 1997: Residents of the 70 cottages of the Spanish Camp area receive eviction notices from the developer

August 1997: Fearful that all the cottages of the Spanish Camp would eventually be demolished, Channel Graham, president of the Preservation League of Staten Island, issued a Request for Evaluation to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

January 2000: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) Chairwoman Jennifer Raab sent a memo to the Staten Island Buildings Department warning them that the cottages of the Spanish Camp were awaiting a hearing for designation but the LPC still had yet to calendar the buildings

February 8, 2001: After a meeting on this date between the LPC's counsel and DiScala’s lawyers, it was clear that the destruction of the cottages was imminent

February 9, 2001: The Dorothy Day Cottages are demolished

October 22, 2015: After a public hearing, the LPC removes the Dorothy Day Historic Site from the calendar because it lacked merit

The vernacular cottages inhabited by Dorothy Day and the Spanish Camp were culturally and religiously significant. Founded originally as a temporary camp for the Spanish socialist group, Spanish Naturopath Society, the sense of place embodied in this communal respite encapsulated a divergent lifestyle that proposed development threatened to destroy. Moreover, the Spanish Camp was indicative of a unique type of development - the beach side bungalow community - rarely found in New York City's history. The land-use laws in this case were perplexing. The Spanish Naturopath Society officially bought the 17 acres in 1945, and over the years started selling the cottages to society members while continuing to own the land itself.13 The tenants owned the cottages while the Spanish Camp owned the land. The Catholic Worker bought three of the cottages in 1972. In 1975, the New York City Parks Department designated a portion of the Spanish Camp as open-space land protecting the wetlands.14

Dorothy Day returned to the Raritan Bay, an area where her religious conversion occurred, to focus on reflection, writing, and meditation in the last years of her life. After her death in 1980, the cottage she lived in soon became a shrine to the Catholic community. Historian and friend Jim O’Grady began giving tours of her cottage and the surrounding area.15 In 1997, developer John DiScala purchased the land from descendants of the founders of the Spanish Naturopath Society, in addition to the three cottages previously owned by The Catholic Worker. On July 31, 1997, residents of the 70 cottages received eviction notices from the developer.16 His new development plan included 37 new beach front properties. Before the demolition process started, the residents filed a lawsuit citing a "taking" of property. The residents of the camp lost the court case.17

Fearful that all the cottages would eventually be demolished, Channel Graham, president of the Preservation League of Staten Island, issued a Request for Evaluation to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in August of 1997.18 In the request to then-Chair Jennifer Raab, Graham argued that the cultural significance and the physical integrity of the surrounding area were sufficient for the designation of a Spanish Camp Historic District. At this point, several cottages were still intact. Although the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission did not calendar a hearing for potential landmark designation, they contacted John DiScala in order to reach a negotiation to preserve the remaining cottages. DiScala agreed to donate the cottages to a not-for-profit organization, Friends of Dorothy Day Cottages, and to donate a tidal pond on the property to the New York City Parks Department; however, the agreement was non-binding.19 The Friends of the Dorothy Day Cottages began to assemble a plan to preserve the cottages and possibly reuse them as a museum for the Dorothy Day Catholic Workers Movement. Meanwhile, the Spanish Camp Preservation Coalition served as an umbrella organization that included Friends of the Dorothy Day Cottages, the Preservation League of Staten Island, the Historic Districts Council, and Place Matters. These groups continued to petition the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the buildings over the next four years.20

Still, then-Chair Jennifer Raab did not calendar the buildings. Tensions began to rise between the developer and preservation groups. DiScala frequently complained that the process of designating the buildings was taking too long, further increasing the development costs. Furthermore, he began to doubt that the cottage even belonged to Dorothy Day, issuing statements like “where’s the proof that this woman lived in this cottage?”21 The developer had a record of 17 buildings department violations, and demolished 14 of the camp cottages without a permit.22 Still the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission declined to calendar the buildings for a hearing. In January 2000, Jennifer Raab sent a memo to the Staten Island Buildings Department warning them that the cottages were awaiting a hearing for designation but still had yet to calendar the buildings.23 After a meeting between the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission's counsel and DiScala’s lawyers on February 8, 2001, it was clear that the destruction of the cottages was imminent.24 The LPC finally calendared the buildings. However, it was too late: DiScala had already obtained a permit from the Staten Island Buildings Department to demolish the cottages. On February 9, 2001, the Dorothy Day Cottages were demolished.25

Concern arose over whether the permit was fraudulent. In March of 2001, the Department of Investigation demanded all records from the Staten Island Department of Buildings, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and the Department of Planning.26 The investigation discovered that DiScala had doctored a previously issued waiver from the Department of Buildings. The company was fined $2,500, and soon after went bankrupt.27 After the Dorothy Day Cottages were demolished, the Spanish Camp Coalition steadfastly petitioned the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission to hold a hearing for the four remaining cottages to be designated as a historic district. The Spanish Camp Historic District would include the site where Dorothy Day Cottage was located; "Broadway," an unpaved lane leading to the beach and Seguine Pond; and one of the cottages that had belonged to The Catholic Worker and was frequented by Dorothy Day.28 The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission calendared the district for a designation hearing but it did not move forward until the Commission's Backlog 95 initiative, a plan to address the backlog of 95 properties that had been under consideration for designation, but were never designated or acted upon. After a public hearing on October 22, 2015, the LPC removed the Dorothy Day Historic Site from the calendar because it lacked merit (i.e. the site no longer existed).

In 2007, Wagner College held an exhibit of the Spanish Camp History with a panel discussion, "Spanish Camp: Place Matters," concerning landmark designation of culturally significant sites.29 In addition, the Staten Island History Museum held an exhibit, "This was our Paradise: Spanish Camp, 1929 to Today."30 The exhibit featured photographs from Michael Falco, oral histories, and a visual timeline highlighting the history of the camps as it changed throughout the years. The Spanish Camp and Dorothy Day Cottages represents the changing tides of historic preservation. The role that cultural significance played in this rare settlement pattern in New York City resounded stronger than its architectural merit.

- Dorothy Day Papers

Department of Special Collections and University Archives

Raynor Memorial Libraries

1355 W Wisconsin Avenue

P. O. Box 3141

Milwaukee, WI 53201

Phillip M. Runkel, Archivist

Tel: (414) 288-5903

Email: Phil.Runkel@marquette.edu

- Oral History with Barnett Shepherd

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Phone: (212) 988-8379 - Email: info@nypap.org

- “Dorothy Day Cottages Demolished,” Archive.is: webpage capture. Article retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Ibid.

- Dorothy Kent, Dorothy Day: Friend to the Forgotten (Grand Rapids: Eerdeman’s Young Readers, 2004).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Dan Barry, “Inquiry Delves Into Razing of S.I. Cottages in Line for Historic Status,” The New York Times, 12 March 2001.

- Gustav Niebuhr, “Sainthood Process Starts for Dorothy Day,” The New York Times, 17 March 2000.

- Sherri Day, “Staten Island Cottages Used by Dorothy Day Are Demolished,” The New York Times, 10 February 2001.

- Channell Graham, Letter to Jennifer Raab, Chair of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, 12 August 1997.

- Wayne Barrett, “The Story of the Demolition of Spanish Camp, Annadale, Staten Island, NY,” Village Voice, 2-8 May 2001.

- Dan Barry, “Five Years On, an Emptiness That Lingers,” The New York Times, 7 October 2006.

- Ibid.

- Dan Barry, “Historic Bungalow Camp Is Facing the Bulldozers,” The New York Times, 14 August 1998.

- Wayne Barrett, “The Story of the Demolition of Spanish Camp, Annadale, Staten Island, NY,” Village Voice, 2-8 May 2001.

- Dan Barry, “Five Years on, an Emptiness That Lingers,” The New York Times, 7 October 2006.

- Karen Hsu, “Last Stand for Dorothy Day?” The New York Times, 6 July 1997.

- Ibid.

- Channell Graham, Letter to Jennifer Raab, Chair of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, 12 August 1997.

- Wayne Barrett, “The Story of the Demolition of Spanish Camp, Annadale, Staten Island, NY,” Village Voice, 2-8 May 2001.

- “The Spanish Camp Preservation Coalition Nominates The Spanish Camp Historic District for Landmarks Designation,” Archive.is: webpage capture. Article retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Dan Barry, “Inquiry Delves Into Razing of S.I. Cottages in Line for Historic Status,” The New York Times, 12 March 2001.

- Wayne Barrett, “The Story of the Demolition of Spanish Camp, Annadale, Staten Island, NY,” Village Voice, 2-8 May 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sherri Day, “Staten Island Cottages Used by Dorothy Day Are Demolished,” The New York Times, 10 February 2001.

- Dan Barry, “Inquiry Delves Into Razing of S.I. Cottages in Line for Historic Status,” The New York Times, 12 March 2001.

- Dan Barry, “Five Years on, an Emptiness That Lingers,” The New York Times, 7 October 2006.

- “A Remarkable Press Conference at Spanish Camp: Bungalow Brouhaha says The Staten Island Advance,” Archive.is: webpage capture. Article retrieved 16 April 2016.

- “New History Exhibit: ‘This was our Paradise’ Spanish Camp 1929 to Today,” Staten Island Historian, October 2007.

- Ibid.