Carol Greitzer

Former New York City Council member Carol Greitzer speaks about her time as a community advocate in Greenwich Village, both as a volunteer and city councilwoman, from the 1950s to the 1990s.

Carol Greitzer moved to Greenwich Village in the 1950s where she quickly became involved in local issues including converting the Jefferson Market Courthouse to a public library and closing Washington Square Park to traffic. She was involved with the Village Independent Democrats before running for the New York City Council in 1969. Some of the issues she speaks about are advocating for a unified Greenwich Village Historic District, lobbying to amend the Multiple Dwelling Law to include artist housing in M1-zones, and fighting against the Lower Manhattan Expressway. As an advocate, she often testified before the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and shares the citizen’s perspective on the commission. She also sheds light into the changes in city government in response to the New York City Board of Estimate being dissolved during her tenure as a city councilwoman.

Carol Greitzer Oral History, Session 1

Q: Today is Wednesday, February 22, 2017. My name is Susan Devries, and this is an oral history recording for the New York Preservation Archive Project, and I’m speaking with Carol Greitzer. So before we kind of delve into the tales of your work in local politics and preservation, I’d love to know a little bit more about your childhood, what kind of led to your interests, and the community, and the built environment. And normally, I would ask people what brought them to New York City, but you actually grew up in New York City, correct?

Greitzer: Right.

Q: Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Greitzer: Well, I was born in Manhattan on Fifteenth Street in a hospital that’s no longer there. I grew up in the Bronx, the north Bronx. My father, who is a native New Yorker, was interested in the history of New York and he took me around to a lot of places. Also we had—my mother had a lot of—my mother grew up largely in Milwaukee, and she had a lot of relatives and friends who came to visit us, and my father would then conduct a little historical tour with them. So I got to see the Statue of Liberty several times and other places. I think that’s probably what started it.

Then I—we lived a few blocks from Poe Park and I used to play in Poe Cottage as a child. I would run through it every time we went to the park. I couldn’t imagine two adults sleeping on that bed, that Virginia Poe [Virginia E. Clemm Poe] died in apparently.

Then I found out that the cottage had been moved. Its original site was across the street on Kingsbridge Road. When I was still in elementary school, I did a composition on that and I know I went by myself, I rang the doorbell on this house, and told the woman I was going to write an essay, or whatever I called it. She took me into her dining room and she said, “This is approximately where the cottage stood.” And I wrote something about it. I not only had an interest in historical buildings but I had an interest in [Edgar Allan] Poe [laughs].

Q: And you pursued that to write the paper. Do you remember how you did on your paper?

Greitzer: I have no recollection what it was about or anything about it. I can just recollect standing there. And I’m surprised now, because I was a very shy child, and the fact that I went and did this was sort of remarkable to me [laughs].

Q: And did your love of Poe continue?

Greitzer: Yes, I was interested in Poe. I did, you know, readings on him and his literary criticism and other stuff.

Q: And how did you end up in Greenwich Village then, growing up in northern Bronx?

Greitzer: Oh, I think a lot of people want to go to Greenwich Village. Well, I was living in Washington with my first husband and we had one week when we knew we were coming back to New York. We had a weekend to try to find an apartment and we found one here. We got the advanced sections of The [New York] Times. We got the real estate section the day before it was distributed really. I found somebody was subletting an apartment a few blocks from here on Abingdon Square in the West Village. And when I was having a baby, the landlord, which was Bing & Bing, a famous New York landlord, got me this apartment where I am—where we are today. This is the two-bedroom rather than the one-bedroom.

Q: I think it’s great.

Greitzer: So I’ve been here for a long time [laughs].

Q: Now you had gone to NYU [New York University], correct, for school, did you?

Greitzer: I went through public schools. I went to Hunter [College] High School and Hunter College. I went to NYU—I got my graduate degree at NYU.

Q: Okay. And while you were in school, either at Hunter or NYU, were you continuing this kind of interest in New York City history and the built environment?

Greitzer: No. I don’t think did. I didn’t do much until I came back and lived in the Village. I mean I wasn’t involved. I wasn’t involved in politics. I wasn’t involved in preservation. I couldn’t [laughs] say that I was, you know.

Q: So you moved to the Village. Would this be in the mid 1950s about?

Greitzer: Yes. Right.

Q: And do you remember—I mean you—at the time, in the 1950s and the 1960s, the Village is kind of this hot bed of activity, right. There is so much activism going on.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Do you remember what particular cause first drew you in or was it a particular person that you got to know within the Village?

Greitzer: Well, we wanted to become active in the Village and we went to meetings of the Greenwich Village Association, which was a big thing in those days. It doesn’t exist anymore. But we found that there was a tight group that kind of controlled the organization.

Q: This was Tony [Anthony] Dapolito. Would he have been—?

Greitzer: I don’t know that he was.

Q: He was—okay.

Greitzer: He was on the community board.

Q: Okay.

Greitzer: I can’t recall who was in the GVA [Greenwich Village Association] specifically. But then 1956 came and there was a Stevenson [Adlai Ewing Stevenson II] campaign. When I was in Washington I had done some work there in the Speakers Bureau during the campaign. Then here, someone I was working with here told me she had a friend who was in the process of forming a Village Stevenson group. So that’s how I got involved with the Village—what became—after that campaign became the Village Independent Democrats, [pause], in December of 1956.

Q: And what kind of—so in 1956, you’re starting to get active—

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: —in the Village Independent Democrats. What kind of activities were they taking part in?

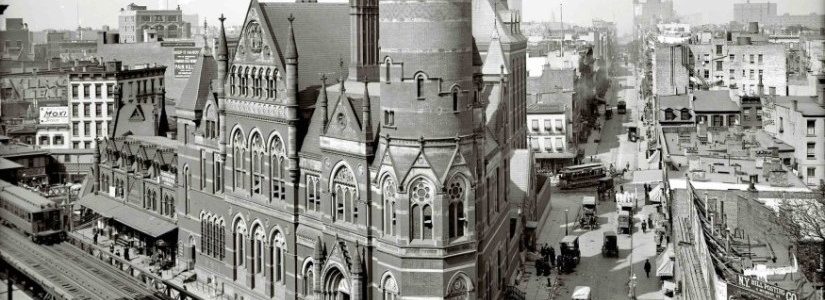

Greitzer: Well, political. But then I got involved in what was going on in the Village in terms of the preservation stuff, and that was, at that time, Washington Square Park was active, and saving the [Jefferson Market] Courthouse, as I said, in December Christmastime in 1957. No, not—oh, gee, was that, um, I don’t know. I’m trying to think which year it was. I’ll have to refer to my notes [laughter].

Q: That’s all right.

Greitzer: I know it was Christmas. I organized a children’s treasure hunt.

Q: Oh, right. I think that was 1959.

Greitzer: Yes. Yes. Yes.

Q: I think that was 1959. Yes.

Greitzer: Probably ’59. Yes. Soon as said ’57, it didn’t sound right. I—oh, I knew the editor of Q Magazine at the time and he gave us a lot of publicity on it. So we had a very nice turnout of kids for this treasure hunt, which culminated, as far as the treasure aspect of it went [laughs], with them going to look at the courthouse building, and we asked the question of whether they thought it would make a nice library. It was a very leading question and they all said yes—[laughter]—so that we could report that to the press, and then we gave them hot chocolate and cake or something up at the clubhouse. That was one campaign that I was involved in.

Then, as far as I’m concerned, the highlight for me was the day that we went down to see James Felt who was the chair of the [New York] City Planning Commission at the time. Everybody—that must have been in 1960, because I was president of VID [Village Independent Democrats] in 1960, and I went down as president of the club, and then the leaders of every other organization went down there. There were really a lot of people. I would say about—my recollection now is that there were forty or fifty people in that huge room that he had. Everybody went around the room talking about what a library would mean to them, and what the building meant to them, and everything.

Then I came—Tony Dapolito drove some of us home back to the Village in his bakery truck and Ruth [E.] Wittenberg, E.E. [Edward Estlin] Cummings, and I, were his passengers. So I had this opportunity to chat with E.E. Cummings, so that was fun.

Q: That’s fairly marvelous.

Greitzer: Yes. Yes. Anyhow, we did get the library. That was a big, successful ride.

Q: Do you remember how—so the scavenger hunt that you did for the Village Independent Democrats, you’re already at that point—this is December ’59—

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: —already knew that you want—that was an idea for that building to become a library. Where did that kind of thought emerge, that goal, that vision of it becoming a library, was that with the Village Independent Democrats?

Greitzer: No, no, no. No, that was—

Q: The community?

Greitzer: That was a community thing and then Philip Wittenberg and Margot Gayle co-chaired that activity and organized people, you know, to work to save it. That was really a relatively easy campaign. I think there must have been people in the city government who were in favor of it to begin with. It worked out all right.

Q: It did happen fairly quickly compared to other campaigns—

Greitzer: Yes. Yes.

Q: —I’m sure that you were involved with. Now about the same time, you were also involved—there was so much going on in Washington Square Park as well.

Greitzer: Yes. Yes. Right. Right.

Q: And how—again, was that—was your way into that work through the Village Independent Democrats as well?

Greitzer: Not really. I think I was the one who was active in it. It was—that started earlier because it started by—Shirley [Z.] Hayes was the main force in that. She doesn’t really get enough credit today. So I, you know, try to point it out whenever [laughs] I can—

Q: Absolutely.

Greitzer: —that she was the one who started it and she organized a whole bunch of mothers. I was not a mother at that time so I didn’t go to the playground. I didn’t really know those people at the beginning. She and other mothers started the organization that led to various—there were at least two committees to save Washington Square Park or to close it to traffic. I did get—I got involved in it but I came a little later to the thing.

But then in 1963, I know Ed Koch [Edward I. Koch] was running with me for district leader. I was already a district leader and he was running for the first time, and we did have the experience of close—of pushing, symbolically pushing, the last bus out of the park one night at about midnight or so.

Q: And was that a planned activity or spontaneous [laughs]?

Greitzer: Yes. Yes. Oh, yes. No. We went there. It was a photo-op. Unfortunately I don’t have the photo. I know it appeared in one of the local papers and nobody has ever seen it since. But I know that it exists [laughs] because I have seen it.

Q: I have seen photos of the symbolic car going through the arch. But I have not seen a symbolic photo of the bus. I’ll have to see if I can hunt that down.

Greitzer: Well, the bus went around—it used it as a turnaround.

Q: Right. And some parking as well, correct? There was some temporary bus parking as well.

Greitzer: Maybe if it—yes. Maybe because the driver might have had a—well, yes, they could have parked there and then used the restroom facilities in the park, because that’s what they usually do with bus drivers. They give them a place to park where they can go and use the facilities.

Q: So what if—so you said that was kind of personal?

Greitzer: The bus situation is a very sore point even today, because the buses used to go north on Fifth Avenue, then they made it one-way, and the buses moved over to University Place, which was then a two-way street. The community then agreed to make it one-way so that the bus could turn more readily from Ninth Street into University. And then it went up University, it had to wiggle around a bit, but it ultimately went up Madison Avenue to the Upper East Side.

A few years ago, the city in its infinite wisdom [laughs], or I should say MTA [Metropolitan Transportation Authority] moved it over to the Fourth Avenue, which is—was two avenue blocks east of University Place and three avenue blocks east of the original route on Fifth Avenue so that it is no longer even serving the Village hardly. It’s really sort of the boundary between the Village and what they call the East Village. So we don’t have good bus service, which is—[laughs].

Q: Well, you’ve certainly seen since not only with that project with Washington Square Park but you’ve been involved in the park in different forms over the years. You’ve certainly seen the changes over time and the impact of some of those decisions. But I was wondering—you said that you got involved in the park issue as more of a personal issue rather than through originally the Village Independent Democrats.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Was that just your love of the park? Like what drew you to want to be involved in that particular battle?

Greitzer: Well, I don’t think it was a great philosophical decision [laughter]. It was the case of, you know, if you have a park, it should be a park and not have a bunch of traffic, not only disrupting it, in terms of traffic but also the air quality, the fumes from the buses, and the other traffic were not desirable.

Q: And you—

Greitzer: More recently, I was involved in trying to save the Pavilion in Union Square Park for recreation use. It’s been turned into a restaurant—

Q: Right.

Greitzer: —which we think is illegal, because it used to be an adjunct recreation facility for children, and it should have gone through—it’s an alienation of parkland. It should have been referred to the [New York] State Legislature, which is the only body that can remove something from park use. Of course, this was not a permanent removal. It was a question of it being a lease, if I was to be very technical, and I don’t think you’re interested in that [laughter].

Q: Well, I think it is interesting though these kind of intricate details that you do get involved in when you’re dealing with—in parks, and city land, and you’re getting involved in that level of advocacy. There certainly are a lot of different motivations and methods that preservation groups and people use, and you certainly were—there were so many groups that were active in the Village at the time. You mentioned—was it the Greenwich Village Association?

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Then there is the Village Independent Democrats. There are other groups—

Greitzer: Yes, there was—

Q: —that were working at the time.

Greitzer: Yes, there was the regular club, the democratic club, there was the republican club that was active in the Village at that time, and, you know, things like Kiwanis and—

Q: And I’m curious, did those groups tend to come together around certain issues—

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: —or were they more identifiable through different kind of—?

Greitzer: No. They came together on the—even though a lot of them were very hostile politically; they came together on the issues. And furthermore, in terms of coming together, you had these groups that were active say in one fight and then there would be another thing happening. You didn’t have to stop and reorganize people—the organizations existed. You know, just a couple of phone calls on an issue could get everybody out to testify and to be active again. During the ‘60s, there were so many things going on. There were so many other things. There was the thing that brought Jane Jacobs to sort of prominence in a wider area was fighting the Title 1 designation that Robert Moses wanted to inflict on the far West Village, fourteen blocks I think. So that was a big fight. Then there was the—then she, of course, got involved in the Lower Manhattan Expressway fight. And those were the fights that we all joined in on [laughs].

Q: So you would cross paths with people on many different—

Greitzer: Yes. Right.

Q: —kind of fights. One person that I did want to ask you about, you mentioned Shirley Hayes, which I’m glad that you did, that’s important to remember. And then also Ray [Raymond S.] Rubinow who was—he was part of the Joint Emergency Committee, correct?

Greitzer: Yes. Yes.

Q: And so did you work with him on both the Washington Square fight and anything else in other ways?

Greitzer: I didn’t. No, I did—well, I knew Ray Rubinow because he had been active politically in the Stevenson fight and was sort of helpful in organizing us. I really did know him in that context. But the Joint Emergency Committee, as far as I could see, was an effort to remove Shirley Hayes from the leadership in any of this. I think they felt she was too strident and naïve politically maybe, and these political pros were going to come in and save the day.

Q: And you were working altogether with a different group of people.

Greitzer: Well, I don’t say—yes, I don’t say that I was working that much on it. You know, I came to the events that were scheduled that kind of thing.

Q: And you mentioned that you were I think you said running for district leader at the time as well and I’m just curious about your decision to kind of run for office. Like when did that emerge when you decided to both first kind of run for that district leader position and then later [New York] City Council, how those kind of political decisions were made?

Greitzer: Well, it was slow because I—well, my husband ran for district leader first in 1957 against DeSapio [Carmine G. DeSapio] and he did fairly well considering that he was a novice and DeSapio was a very powerful guy, and the club took encouragement from that. I was on the Executive Committee. Then in 1960, I decided to run for vice president. We had three vice presidents and I was not anyone who made a lot of speeches and that kind of thing, so vice president was a big step up for me.

Then Ed Koch who had briefly joined the DeSapio club thinking that he could bore from within, so to speak, [laughter], soon found out that that was not going to happen, and he came back to VID, and he said he was going to run for president. I thought to myself, if he can run for president, I can run for president, because I never did such a stupid thing as leave with the thought of boring from within. I ran for president and I beat Ed Koch and became president. Then the next year, when they needed a candidate for district leader, I was the logical candidate for the—there are two, there’s district leader male and district leader female, those were the official titles. So I ran for the female position [laughs].

Q: And in that role, did you find yourself more immersed in some of the preservation and community kind of issues that were happening at that time?

Greitzer: Well, yes, those were key issues. I mean I had—I was active in several. I did the—I was active in The Cooper Union and the—how can I describe that? It was—I had a deep throat at the Metropolitan Museum who informed me that the Metropolitan was active in a study. I don’t know whether they were doing the study or whether they were a key component in it—a study of what to do with Cooper Union’s collection. I guess Cooper Union was in trouble then, financially, and they wanted to do something with their art. They had a collection, it was—they like had a collection of laces, and had a collection of pottery maybe, and all different kinds of things, and each one of them alone did not have a very high value. But as they combined collections showing the influence of one category over another, it was apparently quite important. The study was trying to break up the collections and my informant thought that the Metropolitan wanted to get certain aspects of the collection and didn’t care about the others. That was the gist of it.

And I made a big fuss about it and I got enormous publicity in The Times and the [New York] Herald Tribune, each did big stories on it, and I was just the president of an insurgent club at the time. Ultimately, it turned out that there was—again, [laughs], there was a high-powered committee that was very annoyed at me because they were doing all of this stuff secretly behind the scenes and I was the one who broke the story. I didn’t know about them at the time. Mrs. Javits [Lily B. Javits] was one of the people involved. She’s one name I can remember from that group. I mean the ultimate thing was that the collection was saved and it became a part of the—

Q: The Cooper Hewitt right?

Greitzer: Yes, right.

Q: Which is an amazing collection.

Greitzer: Yes. Yes. So—oh, and then one day, somewhere in that time period, I’m trying to think of—I can’t think of the dates, I might have them in here—what is now the Papp Theater [The Public Theater], that building is being vacated by HIAS [Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society], which was a Jewish organization. In fact we—well, we went in there with Joseph [H.] Hirshhorn who was looking for a museum to house his collection. I don’t know how I got together with him. I can’t recall what prompted that. But we went in with James [Grote] Van Derpool who was the first director of the [New York City] Landmarks [Preservation] Commission, and I think somebody who worked with Joe Hirshhorn. We went looking through the building. He was very enthusiastic about that building because he was born on the Lower East Side and he felt that the building stood between the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, which was the art center, and it was a romantic idea that he had. I was showing him how we could close off one of the streets that was a kind of redundant street on one side of the building.

Then he brought Philip [C.] Johnson to look at the thing and Philip Johnson—I was not present but I was told by somebody who was there the day that Philip Johnson came—Philip Johnson jumped up and down on the floor of the building and said that the floor wasn’t strong enough to hold any heavy sculptures that Hirshhorn had in his collection. Of course, Johnson I guess wasn’t interested in remodeling a building. He wanted to build his own building. And then President [Lyndon B.] Johnson wooed Hirshhorn with a site down in Washington and they have the Hirshhorn Museum [and Sculpture Garden] down there and we didn’t get it.

At any rate, then one day, right after all of this happened, Milton Mollen who was then—later he was a judge but at that point he was the head of the one of the housing agencies, and I was there to see him on some matter. I was waiting in his entry room to get in to see him and he came out and he said, “Come on inside, I want you to meet someone.” That someone was Joe [Joseph] Papp, who was looking for an indoor site for a Shakespeare festival. So he asked me about whether the basement of Jefferson Market [Library]—it was in the process of being remodeled and he asked me whether I thought the basement might be available for a theater. They had—I know the Equity Library Theater group had used the library that’s lower down in the Village on Hudson Street, that branch, for dramatic performances. And I told him, well, no, they were going to put the reference room in the basement that had this vaulted ceiling, which might not be too suitable anyway.

It never—it really did not occur to me that anyone who was interested in that small space would be interested in that huge building, and so I did not suggest that building. But I did get credit from people [laughter], because they knew I had been involved with the Hirshhorn thing. So people—a lot of people thought that I helped Joe Papp get that building, and I did not. I can’t take credit for that. But I did sort of become friendly with Papp and he used to invite me to some of the performances, so that was nice.

Q: That’s great. And you mentioned Van Derpool, which kind of leads to a nice segue about kind of the Landmarks Law [New York City Landmarks Law], which is also all—you’re involved with Jefferson Market Courthouse, Washington Square, all of these other things are going on at the same time that the Landmarks Law and the battle for designation in the Village is going on. I just wondered if you had any memories you could share—

Greitzer: Oh, yes.

Q: —about that process, both generally and in the Village?

Greitzer: That was really—originally they were suggesting a huge number of little districts. I think it was something like fourteen, or eighteen, or I’m not sure, it was a number up in the teens, and we wanted one big Village district. So there was a lot of fighting over that. Then there were lots of tours that we scheduled taking people to the old [New York City] Board of Estimate and other people who were likely to be opinion makers on this issue, and we took them on tours. Everybody was very interested in Weehawken Street. I don’t know if you know Weehawken Street.

Q: Yes. Yes, I do. Yes.

Greitzer: Yes, because nobody had ever seen Weehawken Street. So they found that was very quaint and they always had the little framed building there that some people thought was the oldest building in the city. It apparently is not, but it did have that reputation. I remember I took few different—I was present at a few of these tours. I don’t’ remember which city official [laughter] we were trying to influence but I know that I did it a couple of times, taking them.

Q: And when you say, we, are you talking—which group are you talking about that you wanted a larger district?

Greitzer: The other people in these various groups that we mentioned were always available so that it—

Q: It’s people from all different organizations coming together—

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: —around this issue.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Do you remember much about the law itself and the passage of the Landmarks Law itself and any advocacy in the Village surrounding that?

Greitzer: No. That sorted merges—all of those landmarks efforts sort of merged together and I can’t recall whether it was to get the law passed or to, you know, work on the districts. There was a lot of testifying and a big fight over the exclusion of the south Village and the far West Village, the waterfront. I know that we made special efforts on trying to get the waterfront included and the South Village just seemed to be an area that was being provided for NYU, which everybody objected to. We had fights with NYU on a lot of issues, including all the construction of the Law School [New York University School of Law], which killed that row of nice artist studios.

Q: Yes, House of Genius.

Greitzer: Yes. And their acquisition the southern portion of the Title 1 area there.

Q: Oh, with the housing and then where the library is. Is that the area you’re kind of—the Bobst [Elmer Holmes Bobst Library] area and the—?

Greitzer: No, the library—well, the library is up on the—that was one fight. That was definitely a big fight. We didn’t like the idea of the shadows on the park. But there were different spots around the park, from Bleeker to Houston Street had a sponsor who defaulted. When I was president of VID and John [V.] Lindsay was the congressman at the time, and he was a republican but he agreed to come and speak to our club. So one night he arrived. We were waiting for him to come and I saw this taxi pull up, I’m looking out the window, and then I went to the door to greet him. The first thing John Lindsey said to me—I had never met him before but I started to introduce myself—and he said, “I just got off the airplane, where’s the john.” [Laughing].

Q: A memorable first meeting.

Greitzer: Yes, memorable first meeting. Anyhow, he came and he spoke to the club [laughs] and he said that the Title 1 law provided that if a sponsor defaulted that the item had to go back to public bidding and that that was what he was pushing for the site. But the city wanted NYU—

Q: To have it.

Greitzer: —to have it. And NYU got it and there was no public bidding [laughs].

Q: Anything. So you mentioned John Lindsey coming in. I’m wondering were there other—outside of the Village, were there other organizations involved in some of those efforts, either the Municipal Art Society or other kind of city wide organizations that were taking part in some of those efforts?

Greitzer: Well, I was involved with people from the Municipal Art Society. I know I went on walking tours that they sponsored. I met Henry Hope Reed [Jr.] that way and I guess they were supportive. I don’t recall what specific role they had on any of these things.

Q: Was there—I’m trying to remember, and I should, but I can’t recall if once the—so the District was designated in 1969. Was there any kind of Village celebration after all of that work that everyone did to kind of get the district passed?

Greitzer: I can’t remember [laughing].

Q: Okay. I can’t remember. And were you at any of the hearings at the commission—

Greitzer: Oh, yes. Oh, yes.

Q: —about that designation? What were those like? Were they contentious, were there a lot of people testifying?

Greitzer: When we had those things, we always got a lot of people to come down. We organized well to get them to come down.

Q: And were you at any—at the Commission—were there any public meetings at the Commission itself kind of to support the designation and hearings?

Greitzer: Well, that’s what the—

Q: Yes. But you had them. Yes.

Greitzer: You’d go down there when they would have a hearing.

Q: Right. So you would organize people to take with you there.

Greitzer: Yes. But with the—getting us into the one district was more a matter of lobbying and getting them to agree to do that. Finally, I guess they drew it as one district and that was what we went down and testified on. I don’t recall whether there had been actual testimony on those earlier several districts or whether they were just proposals and then we all indicated that we objected [laughs].

Q: That you had objected to it [laughs].

Greitzer: Yes. But I don’t think that we testified on those. You know I can’t remember the details. I testified so frequently, I mean—they were terrible days because you spend hours there, then they’d break for lunch, and you never knew when they were coming back. Then they would go into executive session in the adjacent room where they really decide on things.

In fact, there was one [laughs] person, whose name I won’t mention who became a judge later, but he was—he used to sit for Lindsay or he came in to sit at a Board of Estimate hearing for Lindsay. At one point, I came up to testify with some people on some issue, I don’t remember what it was. And he said to me—he said, “Well, we’re going to vote now and then you can testify later.” And I said, “What?” You know, I mean [laughter], I was appalled at that. The people, his aids, sitting behind him, there must have been two aids, they both leaned forward, you know and whispered in his ear, and then he said, “Alright, we’ll take your testimony now.” But of course they had already voted in the executive session when they were in the other room. That’s how that works. So it was very rare that you could come and testify and get them to maybe lay it over where they go back into the other room and change their vote.

Q: Right. So the, I’m just going to say, hundreds of meetings that you went to, and the testimony that you gave, was some of this part of your decision to kind of further your political involvement. I mean it’s kind of leading into the designation—well, the Landmarks Law is 1965, the designation in the Village is 1969, and then soon thereafter you’re on City Council, correct?

Greitzer: Yes, but I don’t think—I wouldn’t say that—I mean there were a lot of things. I was very active in parks. I had formed a citywide parks group. I was very involved with traffic, buses. I went—I mean I actually got design changes in both the buses and subway cars. I went to Washington—well, maybe that was when I was in City Council, because I know Ted [Theodore S.] Weiss was in Congress.

Ted Weiss and Geraldine [A.] Ferraro arranged for me to meet with one of the transit agencies in Washington, because they were contributing money to our bus purchases here and they ruled that buses had to have closed windows and an air system, you know, air conditioning in the summer, and something else in the winter. And I went down and argued for open-able windows, because I said most of the year you didn’t use the air conditioning in New York. There were other states that were further north that probably rarely, if ever, used air conditioning, you know, maybe a couple of weeks in the summer, and I got them to change their policy and I got design changes in the new subway cars.

So I was really quite involved in other issues other than preservation. Ed Koch, he ran for Council, and then when he ran for Congress, I just ran for the vacancy that he created. It just seemed like a natural move up for me.

Q: This is maybe a complicated question, but I’m curious about this because the Board of Estimate is kind of a complicated thing to try to understand and it doesn’t exist anymore, correct?

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: It was during your time at City Council, is that correct, that that changed from the Board of Estimate—

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: —to our current format. That happened during your time at City Council?

Greitzer: I’m not sure what year that happened.

Q: Let me see if I can find it.

Greitzer: But it happened—but then it might have been the same time that they got rid of the councilmen at large, because that was the same issue.

Q: Okay.

Greitzer: And so—

Q: I think it was.

Greitzer: —we had Henry [J.] Stern and Bobby Wagner [Robert F. Wagner III] were our councilmen at large and also people that we were—many of us were personally friendly with. And then they got ruled illegal. That must have been the same time as the Board of Estimate. So that would have been—

Q: Would you think then it all finally wrapped in the ‘80s, correct? The 1980s by the time it was all fully—

Greitzer: Wrapped up in what?

Q: The 1980s by the time the Board of Estimate got kind of finalized I think.

Greitzer: I would think it was the same time. It was the same issue.

Q: Yes. Yes, I think it was about that.

Greitzer: But I wish we could do that with the federal government with the U.S. Senate, which doesn’t represent [crosstalk].

Q: That was the sticking point with the Board of Estimate, was it? That there was not a fair representation in all of the boroughs?

Greitzer: That’s right, yes. Well, you had boroughs like Brooklyn and Queens were larger than Manhattan, and the Bronx, and Staten Island. While fairly large geographically, had less population. It was the question of one person, one vote, or as we said at that time, one man, one vote. Ah, hello! [Someone entered the room]

[INTERRUPTION]

Q: We’re almost ready to kind of wrap up, too, but—unless—and we’re open to share any stories we haven’t covered I’d be happy to chat with you about.

Greitzer: I think I have covered all the things.

Q: But in general, I wonder you talked about so many different issues that you were involved with and I would love your observations about maybe how community advocacy has changed over time. You have been involved in projects that, for instance, you mentioned some of the Village districts not getting designated, the south Village, and the waterfront.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Those areas are now finally getting designated. So you’ve seen that kind of time and advocacy change over time. Is there anything that you would think of as kind of a change in how we advocate for our city and the built environment?

Greitzer: Well, I could be wrong but I just have a feeling that advocacy was very new when we did it. I mean there were people—there was a mother’s group that fought Robert Moses when he was trying to destroy a playground up in Central Park West in Central Park. You know they just got wind of it and got out at the crack of dawn with their baby carriages, and stopped that demolition, and that got wide press play at the time. Of course, there were more newspapers back then. But I always had the feeling that we were leaders in that effort down here and that now other people have latched onto the idea of protesting [laughs], and organizing, and people are doing it all over the city.

Q: Are there any issues that we haven’t chatted about that you would like to share? I know you were involved with artist housing. You mentioned some of the Title 1 battles.

Greitzer: Yes. Where did you do all this research?

Q: You can find out amazing things about you online. But also I used to work for the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation years ago.

Greitzer: Oh. Oh.

Q: So I’m—fortunately, this is coming back to me. I remember the tales—

Greitzer: Artist housing, yes.

Q: —about a lot of these issues. And that again was early ‘60s, correct?

Greitzer: That was the day that Jack Kennedy [John F. Kennedy] was shot. We had our first meeting with city officials on acquiring two buildings on Greenwich Street, Twelfth [Street] and Greenwich. Greenwich Street that is not Avenue.

Q: Yes.

Greitzer: Yes, I remember that day very vividly because we had this meeting, and it was this gorgeous day in November, and I walked home from the City Hall area. The meeting was on, a few blocks north of City Hall. I don’t remember the exact street. But I walked home, I called up Mary [P.] Nichols who was the investigative reporter on the [Village] Voice. She was staying in one of the local hotels—we had hotels now that have all become NYU dormitories or else condos—because she was working on some special article. She was saying—when I got to her, she said, “Oh, thank goodness you called.” She said, “I can’t get an outside line.” And then she said to me that the president was shot, and that’s how I heard about it. I put on my radio and held the radio near the phone so that she could hear it because she didn’t have a radio in the room, and we stayed on talking until they announced that he was dead. So I remember that day very vividly.

Q: Yes.

Greitzer: That date I can—

Q: Goodness.

Greitzer: —always resurrect. So we did have a committee that got these two buildings that the city turned over for tax liens. We had—and Jack [M.] Kaplan of the [J.M.] Kaplan Fund helped with some of the money that we needed to get the thing going. Unfortunately, he had a lot to say about how we did the project [laughs], but that—

Q: Was it envisioned as kind of a test case, like a little pilot project—

Greitzer: Yes. Yes.

Q: —to see—to show the city that this could work?

Greitzer: Yes. Well, we had to get—yes, we had to get state legislation. So we had to get the legislators, like Jerry [Jerome] Kretchmer in the [New York State] Assembly, and I guess it was MacNeil Mitchell, I think, in the [New York State] Senate who sponsored the legislation. It was an amendment to the Multiple Dwelling code [New York State Multiple Dwelling Law] to allow artists to live in these M zone [M1 District] buildings. So we provided twelve apartments for artists. Then that same legislation made possible in Westbeth [Artists’ Housing] and SoHo, although it was—a lot of the aspects of the law were ignored by the time SoHo came into being. I mean I don’t think everybody who got an apartment in SoHo is an artist, but many of them were.

Q: And who was working on that initial project on Greenwich with you?

Greitzer: Dan Lion [phonetic], Wally Popavitzio [phonetic] and several of the other people from the West Village group.

Q: Okay. And you mentioned Mary Nichols, who I remember meeting very well. Was she someone that you worked with frequently? I mean she was on the Village Voice and was a reporter, and she reported a lot on obviously what was going on in the Village.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: So did you work closely with her?

Greitzer: You know Mary Nichols was a good friend. I used to say that there were times when she would—there was one occasion when I called her early in the morning to tell her something, and by the evening she called me to tell me the same thing, because she had been talking to so many people during the day she didn’t remember where she had heard this [laughs]. I don’t remember what the story was, but it was some issue.

Q: So it was this pooling of information.

Greitzer: Yes, she was very conspiratorial. But then you sort of have to be if you’re involved in politics or reporting.

Q: Trying to dig out the story or the truth of something. That’s great. Well, we’ve covered—

Greitzer: Yes, I dedicated—this lectures that I did was dedicated to her.

Q: Oh, really! And who was the lecture series for that you did?

Greitzer: It’s Greenwich Village: The Sixties, the Fight for Preservation, compiled in honor of Mary Nichols at New York University, November 12, 1996. You want a picture of that?

Q: That would be lovely. Thank you. It’s good to know that that exists and how lovely that it’s in memory of Mary or in honor of Mary I should say. Are there—did we leave—I’m sure we left some things out. Is there anything else that you would like to chat about that we didn’t—?

Greitzer: Oh, Verrazano Street, I didn’t really mention that. Verrazano Street was a mapped street in the Lower—in Bedford-Downing. There is another street there. It was supposed to be for an extension westward of Houston Street after they—they widened Houston Street from Sixth Avenue East. I don’t know how far east, but east. And they wanted to do an extra block to Seventh Avenue. But at the time that they mapped it, Seventh Avenue was two ways and it would have angled up like this from Sixth Avenue and gone into a northbound street. But by the time we heard about it they still hadn’t done it. Seventh Avenue was now one-way downtown.

So this traffic, which would have gone up like that, would have had to then make an awkward turn to make the left turn to go downtown, and it didn’t make sense anymore and it would have destroyed several buildings. And we found out about it because Edith Evans Asbury, who was a very good Times reporter and a Villager, did a story about it. She found out the city owned all of these little houses on these three streets and that the city was a slumlord. The apartments were in very bad need of repair. So she did a big story in the Times, which is in this booklet. I mean this thing consists—after those three pages, it’s just reprints of stories in the papers that’s what it is with a little bit of commentary maybe.

So we were—that was in 1960. I was the president of the club. Then we went in and painted an apartment and it was like a scene out of the Marx Brothers movie where they take—with the state room scene where they crowd into the state room because the room was a very small room and there must have been a dozen of us in there painting this apartment. But the picture got into the Time, and other papers, and we killed that street ultimately.

Q: So that was your little kind of media splash to show that you were trying to clean up these houses? That the city wasn’t cleaning them up so you were trying to—

Greitzer: Yes, there was that. Plus the fact that we felt that the street was unnecessary.

Q: Right. Right.

Greitzer: It was a stupid one-block extension, which would have killed all of these apartments for all these people. There was one lady I think on Downing Street, I went in, looked at the apartment, and she had a coal burner to heat the apartment. And I said, “Where do you get the coal from?” She took me across the hall to an empty apartment and she had the coal delivered there and this living room of this empty apartment was sky—was ceiling high with coal. That’s where she got her coal from [laughter]. This was in 1960. So along with bathtubs in the kitchen, which still existed at that time, there was coal in the living room.

Q: Right. A whole apartment just for her coal storage.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Oh my goodness. And that project, the Verrazano Street project that’s the 1960s as well?

Greitzer: Well, yes, that was—we—the article—the initial article was in 1960, and then we came and painted the apartment, got the article, and we kept making—oh, we got—Wagner was running in 1961. He was running and the organization was opposing him. He was running for re-election and we got him down there to a rally down there, and he agreed that the roadway didn’t make sense, and he would kill it, and he did eventually. We had to get it de-mapped, which was a procedure. It took awhile.

Q: Well, I want to thank you so much for your time. You’ve shared so much interesting information and I’m sure we could speak for another two hours. But we will stop it here, unless you have other stuff that you would like to share with me, any other stories, or memories. And we can always, if you’re willing, pick up on another conversation if there’s a story that we want to flesh out a little bit more of everything that you have shared. But we’ve covered quite a bit.

Greitzer: Yes.

Q: Thank you.

[END OF INTERVIEW]