Norval White

A former leader of the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York discusses his and the group's efforts to save Pennsylvania Station from demolition in the 1960s.

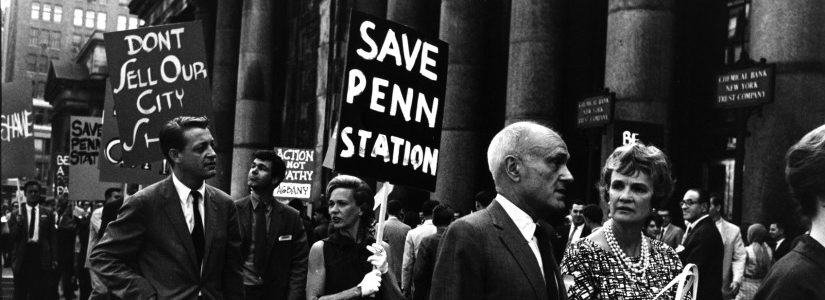

Architect and writer Norval White was a leader of the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York [AGBANY], which organized protests and lobbying on behalf of Pennsylvania Station when it was facing destruction in 1962 and 1963. In this 2006 interview, White recounts his role as chairman of AGBANY and the roles of many of the prominent individuals involved in AGBANY’s activities. White also addresses his activism in the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects [AIA] vis-à-vis the controversy over Penn Station and other threats to historic buildings. He then discusses the public hearings leading up to Penn Station’s demolition and the possibility of a conflict of interest between James Felt, the then-chair of the New York City Planning Commission, and his brother Irving Felt, the developer of Madison Square Garden. Near the end of the interview, White discusses his work with Elliott Willensky as co-author of the AIA Guide to New York City and comments on works of modern architecture that have, in his view, fit appropriately into the context of historic neighborhoods in the city.

Norval White, Session 1

Q: First, let’s start with your name and a little background. You were a practicing architect

at the time of the Penn [Pennsylvania] Station fight. Can you talk about your work in this period?

White: While I was still a graduate student at Princeton [University], we had a visiting faculty member, a partner in the Italian, Milanese architectural firm of BBPR—I love to say the name—Banfi, Belgiojoso, Peressutti & Rogers. The [Ernesto Nathan] Rogers in question was the uncle of the current English Rogers, Sir Richard [G.] Rogers who’s been bedecking London with high-tech structures.

But BBPR was very interesting, in the early post-war, in the 1950s, doing quite radical modern

architecture, but frequently within the context [interiors] of historic buildings. Then there was [Carlo] Scarpa among other Italian architects of that time who relished the bare—you can’t say bones—carcass of their medieval and Renaissance buildings and loved to outfit them with very hi-tech glass, lighting exhibits, etcetera in a kind of dialogue between the old and the new.

Our teacher at Princeton was [Enrico] Peressutti, the P of BBPR. While here he designed a rather wonderful showroom for the Olivetti Typewriter Company [1954, see page 873 AIA Guide to New York City 3rd Edition] on Fifth Avenue. Speaking of preservation, there was a modern interior that should have been preserved. It was quite radical, and quite wonderful, and quite sensuous, with great stands for the Olivetti typewriters, rising in marble; sculptural bases for the typewriters, including one out on the street, that the passing pedestrian could type on it—something which is inconceivable today, with vandalism and whatever. It was a striking, expressionist store, and of course it was destroyed. It had a very short life. A very rich but short life.

I shared offices for my architectural practice with Charlie Hughes [Charles Evans Hughes III] and his minions, with rooms at the front for Jan Rowan and myself—on the parlor floor of a brownstone at 33 East Sixty-First Street, a front room with a bay window, a rear room with a courtyard view and an extension with a small conference room for us both. It was in these rooms and in the conference room way in the rear that we held the meetings to create AGBANY [Action Group for Better Architecture in New York], and to start the organization to picket and make noise about the demolition of Pennsylvania Station.

Q: Can you take us back to spring, 1962, and explain how you became involved with the Penn Station fight? How did you first become aware of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company’s plans, and what were your initial reactions?

White: We had first become aware—we meaning the eventual group of AGBANY. We had first become aware of the railroad’s plans through the general information in The New York Times and other publications. But we were inspired to band together and take some action by a young woman at the time, Diana Kirsch, who as I remember was a South African by birth. She had gone, I think, to the University of Witwatersrand, and interestingly enough, was a classmate, of Denise Scott Brown, who eventually married Robert [C.] Venturi [Jr.] and is a name in her own right in modern architecture.

Diana Kirsch at the time was employed by Herbert Oppenheimer. As I remember, she was the designer for the bank at the north end of Times Square where there is now a very sleek later modern building—but it was a two-story bank, in a Miesian style [Ludwig Mies van der Rohe]. She did it within the office of Herb Oppenheimer. Herb Oppenheimer, of course, is still around and you can ask him about it. But I think the firm was then called Oppenheimer, Brady & Lehrecke. It’s now Oppenheimer [Brady] & Vogelstein.

I didn’t know Diana but she knew others, probably Jordan [L.] Gruzen and Peter Samton. Elliot Willensky was also involved, we had worked together earlier in the office of Lathrop Douglass [Architects]. He later became, of course, my partner in doing the original AIA Guide to New York City. One of the key people who moved away, afterwards, was Jim [James] Burns, who had been on the staff of the staff of Jan Rowan’s at Progressive Architecture, and it was he who invented the name AGBANY, Action Group for Better Architecture in New York. It was a name that the New York State Education Department didn’t like, because when we applied to become a non-profit, educational institution, they said, “You can’t use the word action, because that implies you’re a lobbying organization.” So the actual papers, when they were made, said, “A Group for Better Architecture in New York.”

Q: Can you talk about how AGBANY was organized? How did you become chairman, and what were your duties as chairman?

White: There was a charter. The names of the people involved were on it. That document has apparently been lost. It was, for a while, in the hands of Elliot Willensky; unfortunately Elliot died in 1990. Before that he had looked for it, as I remember, and he couldn’t find it. But if the State of New York issues a charter, there must be some record of it in the coffers of the Education Department, and one might find it there.

One of the reasons I became chairman at the beginning, was the fact that I was older than most of the really active members of the group. The people who were running around and doing the leg work, were people like Jordan, and Peter, and Diana, and so forth. At that time, in 1962, how old was I? I must have been thirty-six years old, and some of them were only twenty-four. The other issue is the Charles de Gaulle syndrome. People tend to elect tall people to be chairmen.

My duty as chairman was to be spokesman, and the person to organize special

events that might support the activities of AGBANY. I should say that, almost from the beginning, we were receiving the moral, and to some extent financial support of the [JM] Kaplan Fund. Ray [Raymond S.] Rubinow, who was the executive director of the Kaplan Fund, was very interested in our project, as a kind of moral crusade for architecture. He introduced us—particularly me—to Jack [Jacob] Kaplan, who was the man who gave the money for the fund. Jack’s fortune was based largely on the purchase of Welch’s Grape Juice, turning it into a cooperative a cooperative outlet for concord grape growers.

Jack was an interesting guy. He is succeeded in his family history by his daughter and son, his daughter, Joan Davidson—Joan Kaplan Davidson—who was at one point chairman of the New York State Council on the Arts; and his son, Richard [D.] Kaplan, who is an architect, and is interested in many good works. I think at the present time Richard is chairman of the Kaplan Fund.

Going back to initial reactions, and why we did what we did, why we were concerned, is the fact that some of us had been trained to have a great sense of historic context. My own experience had been at Princeton with the great French design critic, Jean Labatut, who had steered such leading lights as Robert Venturi and Hugh Hardy on their way, well founded in the interplay of historic architecture with modern design.

[Sound of church bells] By the way, that’s the town bell of my village of Roques, tolling the six o’clock hour—6:00 P.M.—and I’m sitting in my garden terrace overlooking the landscape up to the Pyrenees. I can’t see many buildings in the distance, although I can see a great distance, probably twenty miles—but I can’t see as many buildings as there are one block in Brooklyn Heights. Brooklyn Heights, where I lived for thirty years before I first moved first to Connecticut after I retired from teaching at City College, and then to France.

Q: Explain to me the dynamics of AGBANY. What were the organizational politics? According to Herbert Oppenheimer, with whom we conducted an interview, Philip Johnson and Ada Louise Huxtable were often making announcements for the group, and you and Elliot Willensky and Charles Hughes were sort of pulling the strings. Then you had others involved. Can you talk about this working structure?

White: There may be some confusion in Herb Oppenheimer’s mind. Philip Johnson was speaking on behalf of our group, but not Ada Louise Huxtable. The woman was Aline Loucheim, who had become, by that time, Aline [B.] Saarinen. Aline was an art critic for The New York Times; then when she married Eero Saarinen she re-oriented herself toward architecture. This period, of course, was after Saarinen’s death. But at the time of the actual picketing of Penn Station, we organized a press conference across the street in the then Hotel Pennsylvania or Hotel Statler, whichever of the many names it had in August of 1962. We had the two spokesmen mentioned, Philip Johnson and Aline Saarinen, and also John [M.] Johansen, and perhaps somebody else, but those are the three that I remember. We had organized them and briefed them to speak on our behalf, to the press—which they did—and I think they were certainly on the radio, if not television. I did not own a television in 1962.

There must have been a television reportage of some sort, because I can remember going to Jordan Gruzen’s apartment, because he had television—and looking at something, whether it was the actual picketing we were watching, or part of the press conference. I just can’t remember.

But later on, to bring some real intellectual meat into the conversation, Jan Rowan, who knew all of the big names in architecture, gathered together a group of them. I borrowed the Century Association—the Century Club conference room upstairs. My father had been a member, and I persuaded someone to rent us the room. We had the deans of a group of architectural schools; I remember we certainly had [José L.] Sert from Harvard, I remember, among others. Gosh. What’s the name of the guy from the University of Pennsylvania [G. Holmes Perkins], who was there for years? I’ll think of it in a while, and there were several others. Frankly, I just don’t have a list of the people, but those were the heavy-weight names.

Other editors of other magazines were there. I think that at the time there was still the Architectural Forum, and the editor of that was Peter Blach. Interestingly enough, Peter Blake was a person born in Germany Peter Blach, and gravitated, eventually, to the United States, and became editor of an architectural magazine in the same way that Jan Rowan, my partner, came from Poland, and eventually became editor of one of another architectural magazine, Progressive Architecture. It was a bit as if Jan was an incarnation of Joseph Conrad—[unclear] actually wrote in English but he was Polish. Here were two Europeans who came and ran the English-language architectural magazines in New York. The heavyweights wrote despairingly of the eventual loss of the Station, but Madison Square Garden [MSG] went ahead without a stumble. Are there sane people who are now actually trying to preserve it?

Going back to the original question, “You were a practicing architect, can you talk a little about your work in this period?” I had designed two houses, two big houses, in Tenafly, New Jersey, one of which was published in Progressive Architecture: the Seiden House [phonetic]. It was the first significant opportunity I had to publish a house—not that I did a lot of houses thereafter—but the Forum, under Peter Blach, had also published my country club in River Vale, New Jersey—originally the River Vale Country Club—later renamed the Edgewood Country Club—perhaps a year or two before that. The Architectural Forum article about the country club was in an issue about young architects, and a young architect, at that time, was considered to be somebody under forty years old.

Q: How did people join AGBANY? Did you solicit members, or was there already a group of interested architects established?

White: AGBANY wasn’t actually a membership organization. There was a kind of consensual group of people. Anybody who wanted to be on board was on board; it wasn’t a matter of contributing money, necessarily. Of course, we got some seed money from the Kaplan Fund, as I mentioned before, through Ray Rubinow, who was its executive director. I’m bad at remembering all the names involved accurately, with AGBANY. I’ve mentioned Jim Burns, whom I haven’t seen, probably in almost forty years. I think he went to California, and had another life there. But there was Norman Jaffe, who tragically drowned in a swimming accident a few years ago, off Long Island. He was a prolific designer of rather upscale, modern houses. Charlie Hughes, at the time, was doing, I think, if memory registers correctly, sports buildings for the Horace Mann [School] campus in Riverdale—part of the Bronx; unrelated to my country club in River Vale, New Jersey.

Elliot Willensky, I think, was still working for Max Otto Urbahn—and Sandy [Sanford] Malter was involved, Sanford Malter, called Sandy—and many others. I think Philip Johnson got involved through Jan Rowan, then editor of Progressive Architecture. You must remember, this was 1962—that’s forty-four years ago. Johnson must then have been fifty-six. I remember he came to our office—the office I shared with Jan Rowan at 33 East Sixty-First Street—and was fascinated with the models I had been making for a house on Staten Island, for someone who turned out to be a Mafia legman, and the house was never built. But I did some interesting studies for him, as well as some models, and this intrigued Johnson. Unfortunately, he never picked me up in the same way he picked up Peter Eisenman and Robert A.M. Stern, and gave them a big push into the big time. But, tant pis!

The way I thought he was a Mafia guy was on my way back from Staten Island, through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel. He said, “How much do you want as a down-payment?” I said, “A thousand dollars.” And, pulling a roll of money, just like a gangster movie, out of his pocket, with a big rubber band around it, he said, “Take it from there.” So he handed me the roll, I peeled off $1,000 and we went on our way.

But the house never took off. It was on a great site, near Wagner College on Staten Island—on great, high ground overlooking the Narrows and the bridge.

Q: What were the early resolutions of the group? How did you plan to act on them?

White: The early resolutions, if you can call them that, because they weren’t engraved, of the group were to continue this kind of activity countering other threats to the architecture of the city. We thought it was very important to maintain the counterpoint of history, expressed so beautifully at Penn Station between the steel and glass train shed, which was a very modern thing in a sense. It was equivalent to the late Nineteenth Century train sheds of Paris, which, by the way, Napoleon III called les parapluies de Paris, the umbrellas of Paris, which they were. This was in Penn Station’s case attached to a stone monument, a grand space, a simulation of the space, if not the function, of the Baths of Caracalla. This duality gave great vitality to the experience of entering and going through Penn Station. As I remember Aline Saarinen referred to it as a place for “the celebration of arrival.”

Q: According to my research, AGBANY kept minutes of their meetings. Do these still exist?

White: In reference to the possibility there are minutes of the meetings, the answer is no, not formally. If somebody took minutes, I don’t know who it was, and I don’t know where they went. The went the same place the charter we got from the New York State Education Department went—into somebody’s box in somebody’s attic, in a far-off place.

Q: You said in an interview in 1992 that you wanted AGBANY to be the image of modern architects preserving something that wasn’t modern [New York Times, 1992]. You had Philip Johnson, Jordan Gruzen, Costas Machlouzarides and other important architects together. What kind of effect did this have on preservation as an idea, in the architecture community? With the public?

White: Going back to your comment about AGBANY, “You said in an interview in 1992, that you wanted AGBANY to be the image of modern architects preserving something that wasn’t modern.” I think that’s what’s at the root of it all, that point. Up to that point, the almost, then holy war of modern architects, and the fanaticism of some, that swept aside everything in their path. That’s got to be balanced by working in an historical continuum. Sadly enough, today, when you look at architectural magazines, much of what they’re interested in are the star-performers doing star-buildings, free-standing situations unrelated to the cities they serve. We were very interested in the city itself, as a living and growing organism, replacing itself perhaps in the way that cells in one’s body replace themselves over the whole of your life. Modern architecture should be modern, and historic architecture should be preserved, to maintain this continuum.

I think this idea had considerable impact with the architectural profession, which has always been changing. We went from the Ecole des Beaux Arts of the 1930s and ’40s to the Modern architecture, at first largely imported from Europe—except for Frank Lloyd Wright—in the ’40s and ’50s. In recent years we’ve had Post-Modern architecture, which is a flailing about to bring back historic architecture without any real sense of the true history of it, and without a bow to the needs of the more modern building. Obviously, the classic example is the skyscraper. There were no skyscrapers in the Renaissance or medieval times. It’s a new form, and when you start making grand, new skyscrapers in, let’s say, neo-gothic style, it’s a little bit bizarre.

Q: Let’s talk about the picketing for a minute. August 2, 1962, you had a press conference that day; you had the picketing, and you had an ad appear in The New York Times, tying it all together. Talk about this day. Who organized it, and the sequence of events?

White: About the day of August 2, 1962—the organization of the press conference, and distribution of information to the press, was handled by Jim Burns—James T. Burns, Jr. I can’t remember any more about it than that. I appeared at the press conference, where our spokespeople spoke, mostly involved in organizing the hardware and logistics, the tables, the chairs, the microphones, etcetera. And with me there were others. I don’t remember who it was. It may have been Elliot Willensky. Certainly, Jim Burns was there, possibly Jan Rowan was there. Because he had the title of managing editor, and later editor, of Progressive Architecture, he had a certain status that main people recognized, and would accede to his wishes, to an extent. So he was a go-between, Jan. But, of course, he, unfortunately, is also dead.

The foot soldiers had organized the previous week to prepare for the placards that were used in picketing Penn Station. They were on twenty by thirty inch, made of what we used to call Bainbridge board, which were painted. They were made in my office, in our conference room. We had great fun making up different kinds of slogans. Some of them appear in the photograph that was in The New York Times, and perhaps others appeared in other photographs. But we had a great stack of them, and there must have been six or eight people gathered in that conference room, painting them with tempera. Good god! I’m glad it didn’t rain. Then we would’ve had a messy situation of blurred ideas.

We were terribly happy that Johnson himself came to picket, and that he brought somebody of

social prestige. I remember the name as Mrs. [Elizabeth Bliss] Parkinson, and haven’t looked it up, but as I remember she was a member of the board of trustees of the Museum of Modern Art. That was another chink of support for historic New York, as a serious project of modern architects and their lay allies.

Q: How was AGBANY perceived by other architects? Were you an anomaly in the community, in terms of supporting preservation—speaking out about these kinds of issues?

White: AGBANY was a little like the continuous floating crap game in New York in Guys & Dolls. It grew and lessened, depending upon the date and what was going on. People showed up at the crap game of the moment, and another cast were more involved in the Savoy Plaza [Hotel] affair, and the Brokaw mansion.

[INTERRUPTION]

Q: What was the reaction of the public on that day, in your memory?

White: I don’t know what the public’s reaction was on that day. The Times picked it up, and other magazines picked it up. The general public, I think, was not appalled but just surprised that somebody, a group of people dressed in suits and ties and whatever—obviously middle-class or more—were picketing Penn Station was something that was not in their knowledge, their perceived history. I think this, in the long run, was a great public boost for the Landmarks Commission [New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, LPC]. We’ll talk about the Landmarks Commission later, but things move slowly, and the sacrifice of Pennsylvania Station on the altar of future preservation has been, I think, a well-established fact. The sacrifice brought the public to support the idea of a landmarks law.

Q: Let’s talk about what happened after the picketing. On September 10, 1962, a delegation met with Mayor [Robert F.] Wagner, which included you, Frederick [J.] Woodbridge from the AIA [American Institute of Architects], and Morris Ketchum, Jr. from MAS [Municipal Art Society]. Did their presence have a strong effect on the mayor or the [New York] City Planning Commission?

White: As I recall, the delegation to meet with Mayor Wagner was Fritz Woodbridge—Frederick Woodbridge is called Fritz Woodbridge. He was an architect, between two forces; after historicism and before great modernism. Morris Ketchum—he did shopping centers and was very good at it. Fritz Woodbridge represented the AIA. I was a member of the AIA at that point, and I think I was, then, or shortly thereafter, chairman of the Young Architects Committee. And Morris Ketchum from Municipal Art. I became a member of the Municipal Art Society around 1955, so I’ve been a member for more than fifty years. Although they probably don’t remember that.

Q: Apart from this day, what was AGBANY’s relationship with the AIA and MAS? Were they seriously involved in the Penn Station fight?

White: The Municipal Art Society, at that time, was giving awards for good works, but it wasn’t taking any particular stands on any subject. But of course, neither was the AIA. The AIA was, as a group, equivocal. I remember appearing—it wasn’t on behalf of Penn Station, but it was on behalf of a later fight which I’ll talk about another time—the fight to prevent what was called the ABC plan, which involved tearing down a lot of buildings, including the Tweed Courthouse and the Equitable Building across the street, to make a giant, new civic center, including a very tall office building. The ABC team was Abramovitz, Breines, and Cutler—Max Abramovitz from Harris & Abramovitz, Si [Simon] Breines from Pomerantz and Breines, and Robert Cutler, who was then the managing partner of Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill.

We wanted to stop that, because they were tearing down some good buildings and inserting a new municipal office tower. A lot of people didn’t think highly of the Tweed courthouse, but it had great space [unclear]. It was kind of a maniacal plan. I remember Si Breines, in that instance, referring to us as gadflies. Of course, I thought gadfly was a term of honor.

In any event, it was shot down. When we discussed it at an open meeting at the AIA, which was the largest meeting I’d ever seen at that time. We were in the old AIA quarters on East Fortieth Street. There was a large dining room where you could take meals if you cared to, and in that dining room we had meetings of the general membership. I made a passionate entreaty to the New York Chapter AIA to take a stand on the ABC plan, or on anything else.

So earlier, in relation to Pennsylvania Station, we had great sympathy but not the political force of the chapter—not that the political force of the chapter would ever count for too much. Because architects don’t have much clout. It’s the people with the money who hire architects who have the clout.

Q: After the picketing, the next big event on the historical record is the January 3, 1963 City Planning Commission hearing. Because the proposal for the new Madison Square Garden involved a sports arena, it needed a City Planning special zoning permit. Since there was no functioning Landmarks Law that became the only opportunity to publicly talk about Penn Station. Do you have any memories of that event?

White: As I recall, I did appear, and I did give testimony. The grounds for the testimony was that in order to construct Pennsylvania Station, the city had given the Pennsylvania Railroad the bed of the street—that would be 32nd Street—because the station is a two-block entity. And when the Pennsylvania Railroad could no longer afford to maintain itself, and said it had to sell its station to a developer, which was the reason for tearing down Penn Station, ostensibly, the railroad should have given the street back to the city. And therefore, there was no two-block—there should be no two-block entity, in perpetuity. It had been granted for a function that was a service to the city, and would be turned over to someone who was just making a commercial profit. I mean, the Felt brothers were, at best, devious.

Q: The Landmarks Commission that existed then had been appointed in April of 1962. At that time, [Geoffrey] Platt, first chair of the LPC, was asked about the planned demolition of Pennsylvania Station, and he said, “He personally regretted that his commission had come into being too late to try to save the terminal.” [New York Times, April 22, 1962]. Did you try to get the LPC to become involved?

White: You say that the Landmarks Commission actually came into existence—in April of 1962? Why do I think it really came into existence a couple of years later? Well, I’ll look it up. But you say Geoffrey Platt, who was, the first chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Personally regretted that the commission had come into being too late to save the terminal.” But that was April, and the picketing that we were concerned with was not until August, so what the hell was he doing? I don’t remember trying to influence him, or we just considered that the Landmarks Commission, at the time, was impotent, or was powerless, or didn’t care, or whatever.

So I went and got a copy of the Guide to New York City Landmarks foreword by Mayor Rudolf Giuliani. This particular copy is 1998, and in the beginning—it is edited by Andrew [S.] Dolkart—there is a statement that, “The Landmarks Preservation Commission was created in 1965, in response to mounting public concern over the destruction of so many of New York’s historic buildings. The Landmarks Preservation Commission was responsible for—” blah, blah, blah, blah.

Now that’s not 1962, that’s 1965, and that’s the way I remember it; that it was at the end of the year, 1965, the end of Robert Wagner’s term. The previous organization must have been a Landmarks Committee, not a Landmarks Commission, so that it would be something with little or no power.

Q: Looking at the historical record, it seems that the steps taken in the formation of the Landmarks Commission, the establishment of the Study Commission, the Mayoral Commission, etcetera, were generally a step behind the developers in having the power needed to save Penn Station. There are those who have speculated that then City Planning Commission Chair, James Felt, whose brother was a key player in the Madison Square Garden redevelopment, might have in some way slowed down the process leading to the law, so as not to interfere with the demolition of Penn Station project. Was there any discussion at that time about James Felt’s possible conflict because of the role of his brother? Can you comment about this?

White: The possibility of a conflict of interest between James Felt, who was chairman of the City Planning Commission, and his brother, Irving Felt, the head of the organization creating the Madison Square Garden construction, was there. Irving Felt said “Madison Square Garden will be another landmark. We’re replacing the old with the new.” But the problem is that the Madison Square Garden they built was a ninth-rate piece of architecture with no grand spaces, except for the arena itself, not for the non-paying public. It’s a piece of junk, as far as I’m concerned. It’s far lower in status, in present landmark arguments, than the Huntington Hartford Museum [2 Columbus Circle], which at least had a relatively distinguished birth in the hands of Edward Durell Stone, who was a wild romantic, and thought the grill was the be all and end all for his kind of modern architecture.

I knew Ed Stone. He was one of my design critics in graduate school at Princeton. Thinking back on it, I even knew Frank Lloyd Wright, who was a great friend of Ed Stone’s. He had arranged for our class to meet Wright at a restaurant in Manhattan one time, seven of us in an advanced class. With Stone himself and Wright. This was at the time that Wright was building the “Sixty Years of Living Architecture [Exhibition]” Pavilion on Fifth Avenue, on the site of the future [Solomon R.] Guggenheim Museum.

But Stone, although he can be derided for being hopelessly sentimental, was a serious architect. He had built, with Philip [L.] Goodwin the basic box that was the original Museum of Modern Art on Fifty-Third Street. Charles Luckman, the architect for MSG, should have stayed in his old job, as president of Lever Brothers, a soap salesman.

Q: What else was AGBANY involved with? There was a funeral march at Grand Army Plaza for the Savoy Plaza Hotel on October 2, 1964. Also, there were demonstrations for the Percy Pine House, Brokaw House, and the old Metropolitan Opera House. Did AGBANY

have any involvement with these events?

White: AGBANY, proper, wasn’t really involved in anything else. Some of the members of it were, and a lot of them were in that famous funeral march at Grand Army Plaza for the Savoy Plaza Hotel. The Percy Pine House was much later. No, wait a minute—it’s the Brokaw House I’m thinking of—was much later. The Metropolitan Opera House—I wasn’t even involved from a distance, with a ten-foot pole.

But as to the remnants of AGBANY—actually, Ray Rubinow tried to persuade us to become a more permanent organization. He had an idea that I should give up the practice of architecture and perhaps just teach, and do this—do good architectural politics. Of course, I didn’t.

But there was a reprise with the ABC plan that I spoke of before. The Kaplan Fund gave us money to rent offices so that we could pursue a campaign to prevent the ABC plan from wiping out the buildings, and basically to prevent it from being done at all. It’s kind of a maniacal idea on the part of this self-appointed architectural team.

One thing we did regret is that we weren’t active at the time they demolished the great Singer Building by Ernest Flagg, which was a magnificent building. The U.S. Steel Building is on its site now. I had enjoyed an interview with the president of Singer, at one time. He had an office at the very top of that building, in what could have been classified as minor ballroom. It was bulbous at the top and his office was in part of the bulb. He was a friend of my father’s, Milton [C.] Lightner. A lawyer, who had been a lawyer for the company, and then president. I remember being there, and having extraordinary memories of that great space, and of the building as a itself. It was one of the tallest buildings in the world to have been dismantled and destroyed. The economics of that situation must have been staggering—to take such a good building down and produce the U.S Steel Complex.

Now this led, for Elliot Willensky and myself, to the AIA Guide to New York City. It was only in 1965, perhaps two and a half years later, that we proposed to the New York chapter that we be allowed to write such a guide. There were others who made proposals at the same time, but we expressed our seriousness and showed our credentials, whatever they were and we were allowed to make a sample guide, to illustrate what could be done. This was a fifteen to twenty page leaflet—copies of which are very rare, and I still have one. That was then used by the public relations man of the New York Chapter, (his name was Andrew Weil, Andy Weil) to sell advertising.

So the original AIA Guide was published like a magazine. It had eighty advertisements at $1,000 a piece. And that funding, handled through the New York Chapter, through the treasurer—Lathrop Douglass, our old employer—allowed us to not only buy film, rent cameras, pay subway fares, whatever, but also to hire a graphic designer, hire a printer, and actually produce ten thousand copies of the book. It was prepared for the National Convention, honoring the 100th anniversary of the New York Chapter, founded in 1867 as the first chapter of the national organization, which had founded ten years earlier, in 1857 so 1867 to 1967—which we distributed free to people who attended the 1967 convention.

[INTERRUPTION]

MacMillan published a trade edition one year later, in 1968, which is the nominal first edition of the Guide, and the royalties for that were not money but 18,000 copies of the Guide, sent free to every member of the AIA in the United States. That edition was blue. The original edition was black with brown lettering on the cover. The only thing that McMillan did was to use our paste-ups and add an index, a simple index.

Then we went on, in 1978, to a second edition, in 1988 a third edition, and in 2000 I did a fourth edition. We’re now considering—more than considering—working to put it on the Internet, but at the moment we haven’t decided whether it should be free, the whole damn thing, with advertising supporting the cost, or whether it should be done on some kind of a fee-basis, without advertising.

But, in any event, my hope is that it will be the whole guide, and will be interactive; you will be able to click on maps and get entries; or you can click on an architect’s name and see his works, etcetera. So instead of an index, there would be a graphic way of moving around the Guide. We hope to do another edition of the printed book in 2010. Because I’m in France, and New York is there, and I’m not quite as young as I used to be, I would have somebody else take over the bulk of the work, and it would be a work by “Smith and/or Jones” with White and Willensky lurking in the background.

Somewhat intertwined with all these experiences was my relocation to Brooklyn. I bought a house, with my mother’s help, in 1965, at 104 Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn Heights. There I lived in what was the first landmark district, in a sense, a National Landmark district, which had been arranged by a group headed by Otis Pratt Pearsall, one of your directors. There I was immersed in historic architecture over a wide-ranging piece of history. There was a book about it at the time, Old Brooklyn Heights by Clay Lancaster, which had been supported by—financially, I don’t know—but supported by Otis Pratt Pearsall, and that was just of the buildings built prior to the Civil War [unclear]. To the credit of that community, the Brooklyn Heights Association and others supported the construction of the Jehovah’s Witnesses residences on Columbia Heights, in a modern style, as long as it was appropriate and fit into the context of the city. Therefore, the Ulrich [J.] Franzen building, which is there, was something not only accepted but promoted by the historicists of the community that already lived there.

And some other modern architecture came into Brooklyn—it’s a good example of a modest extension of architectural history in a handsome [unclear] community. There are buildings by Joe and Mary Merz on Willow Place—three or four houses are quite delightful. They’ve done similar things in other parts of Brooklyn, as well. But introducing modern architecture with that skill was wonderful.

We did not however—when the Brooklyn Heights district was designated by the Landmarks Commission, be quick enough to include the block on which the present Pierrepont Plaza building sits, the latter one of the great excrescences of Brooklyn. There was another marvelous building there before, a Frank Freeman building, one of my favorite disappearing architects with disappearing architecture. He designed a number of wonderful buildings which have been, by hook or crook, destroyed. Probably one of his best was the Bushwick Democratic Club [House], on Bushwick Avenue, which had a more than suspicious fire that destroyed it. Of course, this building, the Brooklyn Trust Company, on the site of 2 Pierrepont Plaza.

Freeman did a number of other buildings in Brooklyn—the Herman [C.] Baehr House on Pierrepont Street; the present St. Ann’s School building, which was a men’s club, built as a men’s club—many different styles. He was eclectic. He did the eclecticism with great exuberance [unclear].

Continuing in my practice, I was interested in fitting contemporary buildings into an existing context. Two examples are in the Greenwich Village Historic District, one on the site of the old Village Voice Building at Seventh Avenue, south of Christopher Street. It’s a 750-square-foot plot, and it makes the corner whole again, which of course was destroyed. Seventh Avenue South was cut through in the 1940s. A whole series of buildings along it have fulfilled the geometry of the new Seventh Avenue, and this was one of the contributors. It is a building in a stripped neo-Georgian style. Perhaps distilled vernacular might be the appropriate term. The other building is at West Tenth [Street] and Hudson, an apartment house, done with an industrial vocabulary, because that was the nature of Hudson Street.

[END OF INTERVIEW]