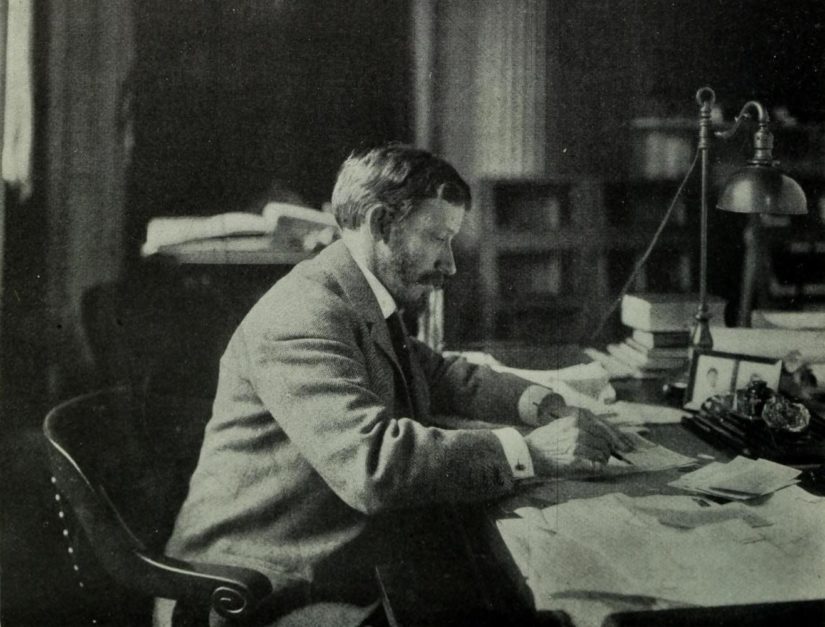

George McAneny

New York’s foremost advocate of planning and preservation in the first half of the 20th century, McAneny helped create the National Trust for Historic Preservation and preserve City Hall, the Battery, and Castle Clinton.

Born in 1869 in Greenville, New Jersey, George McAneny became a journalist after graduating from high school.1 In 1892, he was hired as the secretary of the National Civil Service Reform Association. In 1902 he went to work for the lawyer Edward M. Shepard, who put him to work on the negotiations between New York State and the Pennsylvania Railroad over the plans for New York City’s Pennsylvania Station.2 McAneny became president of the City Club in 1906 at a time when the club uncovered corruption among elected officials and contributed to one of the first city planning conferences.3 He was elected Manhattan Borough President in 1909 and President of the Board of Alderman in 1913; in those roles he introduced modern zoning and planning to New York City. At the end of 1915, he resigned to become a business manager at The New York Times.4 In 1927, he became president of the Municipal Art Society and in 1930 he was named president of the Regional Plan Association.5 His final role in public life was the presidency of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, which he held from 1942 until two years before his death in 1953.6

New York Civil Service Commission

Executive Officer, 1902

City Club of New York

President, 1906-1909

Manhattan Borough President, 1910-1913

Board of Aldermen

President, 1914-1916

New York State Transit Commission

Chairman, 1921-1926

Municipal Art Society

President, 1927-1929

Regional Plan Association

President, 1930-1940

Title Guarantee and Trust Company

President, 1934-1936

World's Fair Corporation

Chairman, 1935-1936

American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society

President

New York Civil Service Reform League

Secretary

As Manhattan Borough President, George McAneny helped secure funding from the philanthropist Olivia Slocum Sage for the restoration of New York’s historic City Hall, built in 1811.7 He also brokered a plan that prevented City Hall from being overshadowed by a massive new courthouse in City Hall Park. Due to McAneny’s efforts, the new building was eventually constructed several blocks north instead.8 In addition to protecting views of City Hall, McAneny’s plan inadvertently saved the now-landmarked Tweed Courthouse, which would have been demolished under the original proposal.

McAneny spearheaded a plan to extend Seventh Avenue south through Greenwich Village and connect it with Varick Street, which would itself be widened. The Seventh Avenue extension alone destroyed over 250 historic buildings in the West Village.9 The Varick Street widening threatened St. John’s Chapel, a beloved city landmark dating to 1822. (Trinity Church, which owned the chapel, had wanted to raze it for years in spite of community opposition, and the widening provided a convenient excuse to do so).10 When preservationists raised an outcry, McAneny tasked his newly formed Committee on the City Plan with negotiating a solution that would allocate city funds to shore up the chapel and turn it over to a community group.11 Unfortunately, McAneny left office before the compromise was executed, and in 1918 Trinity demolished the chapel, which was replaced with a modern post office.12

McAneny was the driving force behind the city’s 1916 comprehensive zoning resolution, which for the first time provided residential neighborhoods with the possibility of legal protection against land-use change. He supported the Fifth Avenue Association, a business group that advocated for zoning to stabilize land values, and created the committees of the Board of Estimate that would develop the resolution.13 Edward M. Bassett, who served on one of McAneny’s committees and later became one of the nation’s foremost zoning experts, called McAneny the “father of zoning in this country.”14 The zoning resolution helped protect Greenwich Village from large-scale development after the Seventh Avenue extension was built.15

In 1939, McAneny helped convince the Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, to designate Federal Hall, an 1830s neoclassical building that stood on the site where George Washington had been inaugurated as president in 1789, as a national historic shrine. It was the first historic building in a major city to be so designated under the 1935 Historic Sites Act.16 On the sesquicentennial of the Washington inaugural, McAneny personally announced the designation from the steps of Federal Hall.17 He then became chairman of the Federal Hall Memorial Associates, a group that operated a historical museum in the building.

McAneny successfully faced down Robert Moses in two related preservation battles. As president of the Regional Plan Association, he forcefully advocated against the construction of one of Moses’s pet projects, a gigantic bridge from the toe of Manhattan to Brooklyn that would have overshadowed Battery Park and blocked views of New York Harbor. Due to the persistence of McAneny and his colleagues, the federal government refused to allow the bridge and an underwater tunnel was built instead. The outcome enraged Moses, who had called McAneny “an extinct volcano” and “an exhumed mummy” in a public hearing on the bridge plan.18

Moses, as Parks Commissioner, then determined to demolish the Battery’s historic fort, which at the time was being used as a public aquarium, supposedly because tunnel construction would undermine its foundations, but more likely simply to take revenge against the preservationists. McAneny, who in 1942 became president of New York’s main preservation society, assembled a group of leading citizens to battle Moses in the courts, in the press, and in federal, state, and local legislative bodies. Although the city government was in thrall to Moses, McAneny’s group took him to court to prevent him from proceeding with the demolition. Meanwhile, drawing on his contacts in the National Park Service, with whom he had worked on Federal Hall, McAneny was able to muster federal support for saving the fort and obtained a commitment of funds from the U.S. Congress. In 1949 the city and state finally agreed to transfer the structure to the federal government, and the fort, now known as Castle Clinton, was preserved and restored as a national historic site.19

During the Castle Clinton campaign, McAneny and his National Park Service contacts began to develop an idea for a new organization that would be able to draw on private resources to preserve historic buildings nationwide. In 1947 McAneny became the chairman of the new group, called the National Council on Historic Sites and Buildings, which, on McAneny’s initiative, organized the National Trust for Historic Preservation.20

In the late 1940s, McAneny spoke out against plans to demolish the historic Federal-style townhouses that lined Washington Square North.21 His activism foretold a shift in the overall focus of the preservation movement, which by the end of the 1950s would be deeply engaged in protecting the character of the city’s historic neighborhoods.

George McAneny's daughter, Ruth McAneny Loud, would carry on the preservation torch after his death. She became involved in the Municipal Art Society and served as its first woman president beginning in 1965.22

- George McAneny Papers

Seely G. Mudd Manuscript Library

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

Finding aid is available online here.

Tel: (609) 258-6345

Fax: (609) 258-3385

George McAneny Papers

Manuscript and Rare Book Library

Columbia University in the City of New York

Catalog record is online here.

George McAneny Papers

New-York Historical Society Library

Finding aid is available online here.

"The Reminisces of George McAneny," a series of interviews held by Professor Allen Nevins and Mr. Dean Albertson, January-February 1949. Under the auspices of the Oral History Research Office of Columbia University. Catalogue record is online here.

-

“George M’Aneny, 83, Dead in Princeton: Zoning and Transit Expert Was City Controller, President of Manhattan Borough,” The New York Times, July 30, 1953.

-

Peter Derrick, Tunneling to the Future: The Story of the Great Subway Expansion That Saved New York (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 119.

-

Derrick, 113, 153; “City Club Asks Ahearn’s Removal,” The New York Times, July 26, 1907.

-

Gregory Gilmartin, Shaping the City: New York and the Municipal Art Society (New York: Clarkson Potter, 1995), 181–202.

-

“McAneny Heads Art Society,” New York Herald Tribune, November 30, 1927; “11th Annual Report” (Regional Plan Association, December 1940); David A. Johnson, Planning the Great Metropolis: The 1929 Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs (London: Routledge, 1996), 178.

-

“McAneny Heads Scenic Society,” The New York Times, October 20, 1942; Alexander Hamilton, March 27, 1951, Box 127, George McAneny Papers, Princeton University.

-

Gilmartin, Shaping the City, 334–35.

-

“Conference To-Day on Court House Site,” The New York Times, October 13, 1911; “Court House Site Is Now Determined,” The New York Times, January 19, 1912; Randall Mason, The Once and Future New York: Historic Preservation and the Modern City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 157–64.

-

“Landmarks Doomed for New Avenue,” The New York Times, October 5, 1913.

-

Mason, The Once and Future New York, 73–101.

-

“Report of the Committee on St. John’s Chapel,” December 15, 1914, I.N. Phelps Stokes Papers, New-York Historical Society; I.N. Phelps Stokes to Joseph H. Hunt, March 17, 1915, I.N. Phelps Stokes Papers, New-York Historical Society.

-

Gilmartin, Shaping the City, 337–38; “Post Office for St. John’s Site,” The New York Times, October 8, 1920.

-

Gilmartin, Shaping the City, 181–202.

-

Edward Bassett to George McAneny, December 30, 1919, Box 54, George McAneny Papers, Princeton University.

-

Gerald W. McFarland, Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001), 215.

-

Charles Bridgham Hosmer, Preservation Comes of Age: From Williamsburg to the National Trust, 1926-1949, vol. 1 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1981), 712–13.

-

“Address of George McAneny at the Celebration of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Establishment of the Government and the Inauguration of George Washington as President,” April 30, 1939, Box 2, Folder 9, Federal Hall Memorial Associates Administrative Records.

-

Robert A Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), 664–76.

-

Charles Bridgham Hosmer, Preservation Comes of Age: From Williamsburg to the National Trust, 1926-1949, vol. 2 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1981), 783–91; Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), 76–82.

-

Hosmer, Preservation Comes of Age, 1981, 2:813–32.

-

Wood, Preserving New York, 86–87.

-

Gilmartin, Shaping the City, 379; “Ruth McAneny Loud, Civic Leader, Dies,” The New York Times, January 2, 1991.