Juliet Bartlett

Also known as Juliet M. Bartlett

Juliet Bartlett was one of the original commissioners of the Landmarks Preservation Commission and was involved with the agency’s first designations.

Juliet Bartlett was born in 1898. She joined the Women’s City Club of New York (WCC) in 1933 and was elected club president first in 1940 and later in 1954. In 1941, during Bartlett’s first term, First Lady and former WCC member Eleanor Roosevelt delivered the club’s 25th anniversary address.

Bartlett was tirelessly devoted to New York City. Throughout her life she served on multiple mayor’s committees ranging in foci from courts to juvenile delinquency to zoning. The Women’s City Club of New York held her as an “expert on zoning.”1 In 1954, she wrote “Futurama of New York City,” a brochure for the layman, which outlines and discusses the need for better zoning and long range planning for the city.2

In 1965, Bartlett was appointed by Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. At the time of her induction to the Commission, Bartlett was serving on the board of directors for the Women’s City Club of New York. Apart from her civic career, she was a professional artist and painter. She died in March 1979 at the age of 81.3

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

Commissioner

Women’s City Club of New York

President: 1940-1942 and 1954-1957

Juliet Bartlett had a stored career as a commissioner of the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). Before being appointed to the LPC, she possessed a strong record of civic involvement, particularly in the area of city planning issues. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s she served on various New York City committees and commissions. She was part of the Traffic Action Committee, the Citizens' Conference on City Planning, and the Mayor's Committee for Better Housing.4 Her involvement and passion for New York City led to her appointment as part of the advisory Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1962.5 In June 1965, after the New York City Landmarks Law was passed, Juliet Bartlett was inducted as a member of the new Landmarks Preservation Commission.6 Of the 11 members, she was the only female appointee. As one of 11 members of the Landmark Preservation Commission in 1965, Juliet Bartlett helped determine "what structures merit being designated landmarks because of historical or architectural distinction" and was "empowered to halt the demolition of a designated landmark for up to a year to devise a plan for the building’s preservation.”7

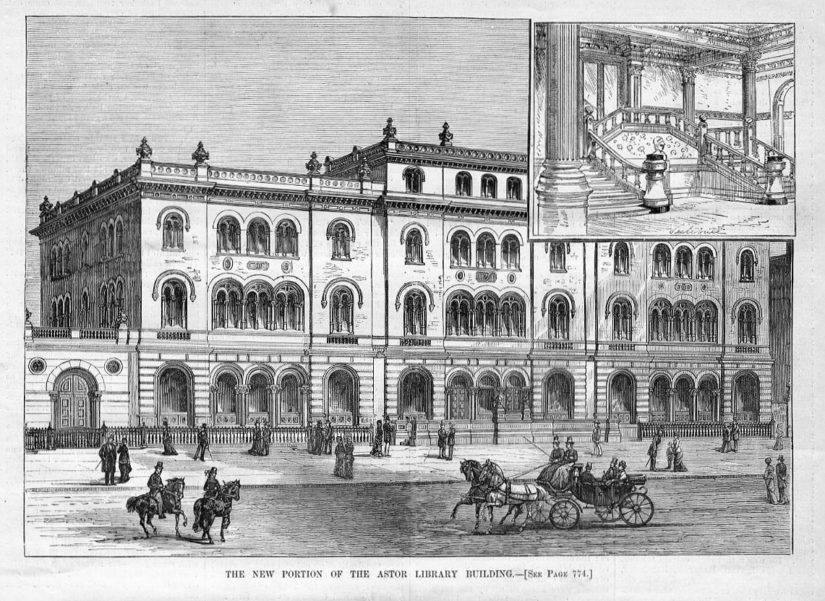

The Landmarks Commission held its first public hearing on September 21, 1965 at 10 a.m. The old Astor Library on Lafayette Street was among the first sites proposed for designation.8 "This 19th-century building, based on the design of a Venetian palazzo, was the city's first major public library.”9 In 1965 the building had been sold to a developer who planned to demolish it. The Landmarks Commission arranged for Joseph Papp, producer of the New York Shakespeare Festival, to buy the building for $560,000 as an indoor complex to add to his existing success with outdoor performances of Shakespeare in Central Park. The architecture critic for the The New York Times, Ada Louise Huxtable, called it "the miracle on Lafayette Street.”10 The salvation of the Library stood as the Landmarks Preservation Commission's first major victory.

In addition, proposals to save 28 buildings including the Metropolitan Opera House and the old J.P Morgan Mansion were up for public scrutiny at the first hearing. The 28 stood out because “their future is now in doubt for one reason or the other.”11 The United States Custom House on Bowling Green, the old Naval Hospital in Brooklyn, the Bronx Borough Hall in Crotona Park, six structures at Sailors' Snug Harbor on Staten Island, and the Kingsland Homestead in Flushing, Queens, were among the buildings they sought to preserve.12

- The Records of the Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. 1915 – 2011

Hunter College Special Archives

695 Park Avenue East 222A

New York, NY 10065

Tel: (212) 772-4149

Finding Aid: 3rd Revised Edition (October 2013)

- Oral History with Frank Gilbert

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Tel: (212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org

- The Records of the Women’s City Club of New York, Inc. 1916 – 2004, Hunter College Special Archives.

- Ibid.

- ”Juilet Bartlett Obituary,” The New York Times, 15 March 1979.

- ”To Head Women’s Club,” The New York Times, 19 May 1954; “New Group Begins Action on Traffic,” The New York Times, 18 November 1947.

- Charles G. Bennett, “City Acts to Save Historical Sites,” The New York Times, 22 April 1962.

- “Mayor Inducts 11 Members Of Landmark Commission,” The New York Times, 30 June 1965.

- Ibid.

- Frank B. Gilbert, “Papp Proved That Landmarks Law Works,” The New York Times, 13 November 1991.

- Ibid.

- Christopher Gray, “The Old Astor Library, Now the Joseph Papp Public Theater; Once It Held Many Pages; Now It Has Many Stages,” The New York Times, 10 February 2002.

- “Landmark Drive to Open Sept. 21,” The New York Times, 7 September 1965.

- Ibid.