Singer Building

The Singer Building, razed in 1967, remains the world’s largest structure to be intentionally demolished.

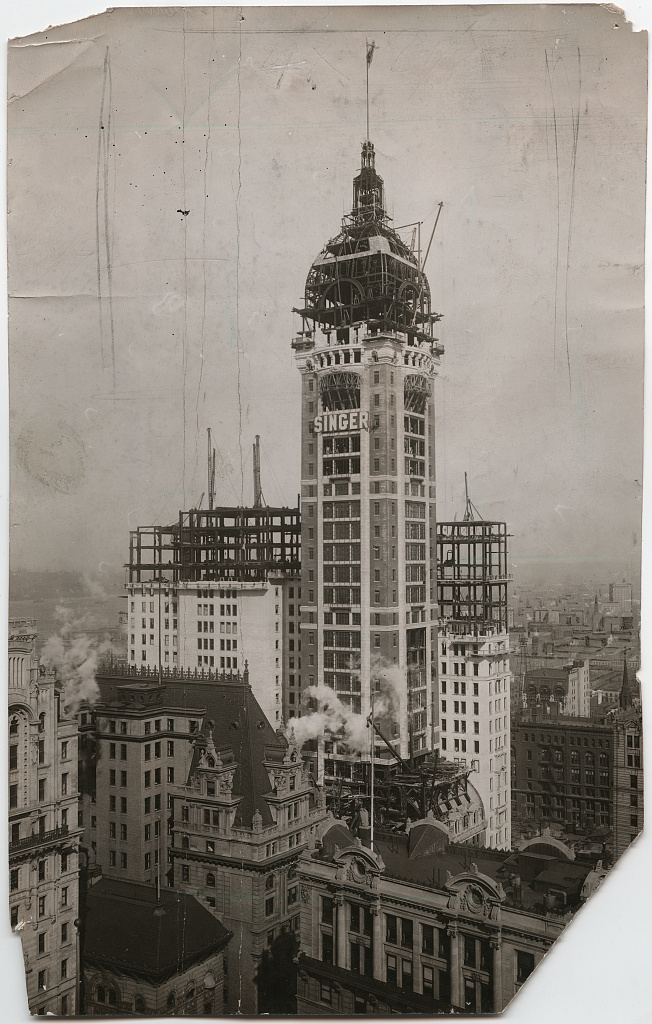

Located at Broadway and Liberty Street, the Singer Building was originally constructed in 1896 by Ernest Flagg for Frederick Bourne, the then-president of the Singer Sewing Machine Corporation. The original structure was red brick and stone with a mansard roof. In 1906, seven years after the completion of the first building, work began on a new building, which was to incorporate the old structure while becoming the “tallest building in the world.”1 The new building was considered to be an engineering feat, towering over the city. The only structure taller in the world was the Eiffel Tower.2 Visitors could pay a fee of 50 cents to enjoy the view from the 40th floor observation deck.3

In addition to the original structure, the new Singer Building included a 612-foot shaft, in the Beaux-Arts style with a bulbous mansard roof and lantern at the peak. The lobby of the building featured marble columns with bronze trim and medallions monogrammed with the Singer name and a needle and thread. The columns rose to meet small, delicately plastered domes. In addition, the lobby was described as having a “celestial radiance,” in the vein of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition architecture of the time.4

The Singer Building was never designated a New York City Landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and was demolished.

1961: The Singer Building is sold to Webb & Knapp

1963: Alan Burnham classifies the Singer Building along with the Metropolitan Life Building and the Woolworth Building as important

1964: United States Steel buys the Singer Building from Webb & Knapp

1967: The Singer Building is demolished in order for a new structure to be constructed for United States Steel

In 1961, Singer Sewing Machine Corporation decided to move uptown and out of the building because it had become "obsolete."5 The property was bought by the development firm of Webb & Knapp.6 Webb & Knapp also purchased the City Investing Building, the only other building on the block, in hopes of relocating the New York Stock Exchange to the site.7

Meanwhile, future executive director of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) Alan Burnham classified the Singer Building as having historical significance in his 1963 inventory of “New York Landmarks.”8 However, it was recognized by Burnham that it would be virtually impossible for the LPC to save the building. According to Burnham, “if the building were made a landmark, we would have to find a buyer for it or the city would have to acquire it. The city is not wealthy and the commission doesn’t have a big enough staff to be a real-estate broker for a skyscraper.”9

United States Steel purchased the site in 1964 after the attempts to relocate the New York Stock Exchange failed. United States Steel intended to build a new 54-story building in place of the Singer Building and the City Investing Building, which later became known as One Liberty Plaza.10

Finally, in 1967, the Singer Building was demolished, making it the largest building ever to be demolished. While the Singer Building was quickly surpassed as being the world’s tallest building, it remains the world’s largest structure to be intentionally demolished.11 When it became clear that the demolition was inevitable, there were many who then fought to save the lobby of the building. However, the City approved demolition of the entire building regardless. The only piece of the building which remains today are chandeliers from the lobby, which were salvaged and installed in the East Building at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.12 The loss of the structure has been described as the “city’s greatest loss since Penn Station” by the AIA Guide to New York City.13

“What was lost in the demolition of the Singer Tower was not only a vital part of the city’s architectural past but a telling lesson in the humanistic urbanism of the tower-base skyscraper type.”14

A History of the Singer building construction: its progress from foundation to flag pole, O. F. Semsch , Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue , New York, New York 10027 . Also available online at Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Singer Building, 149 Broadway, New York. Longitudinal section of tower. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue , New York, New York 10027

Singer's new iron fire proof factory -- designed and constructed by the architectural iron works [graphic] Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library: Avery Drawings & Archives, Columbia University, 1172 Amsterdam Avenue , New York, New York 10027

- Oral History with Geoffrey Platt

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Phone: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Christopher Gray, “STREETSCAPES/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost,” The New York Times, 2 January 2005.

- ”Already Highest Structure In the World,” The New York Times, 25 August 1907.

- Joseph P. Fried, “End of Skyscraper: Daring in ’08, Obscure in ’68,” The New York Times, 27 March 1968.

- Christopher Gray, “STREETSCAPES/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost,” The New York Times, 2 January 2005.

- Joseph P. Fried, “Landmark on Lower Broadway to Go: End Near for Singer Building, A Forerunner of Skyscrapers,” The New York Times, 22 August 1967.

- Christopher Gray, “STREETSCAPES/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost,” The New York Times, 2 January 2005.

- “Presented by The Skyscraper Museum,” The Skyscraper Museum, 23 February 2016.

- Christopher Gray, “STREETSCAPES/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost,” The New York Times, 2 January 2005.

- Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman, New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism between the Second World War and the Bicentennial (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1997), pages 1126-27.

- “Presented by The Skyscraper Museum,” The Skyscraper Museum, 23 February 2016.

- Christopher Gray, “STREETSCAPES/Singer Building; Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost,” The New York Times, 2 January 2005.

- Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman, New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism between the Second World War and the Bicentennial (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1997), page 1126.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 373.

- Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman, New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism between the Second World War and the Bicentennial (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1997), page 1127.