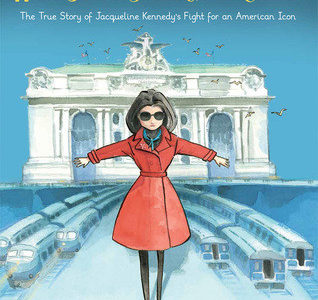

Book Review of “When Jackie Saved Grand Central: The True Story of Jacqueline Kennedy’s Fight for an American Icon”

June 6, 2019 | Dina Posner, former Jeffe Fellow

Book written by Natasha Wing | Illustrated by Alexandra Boiger

Before one even reaches the title page of the new children’s book When Jackie Saved Grand Central, one is greeted by a background of the very same cerulean blue that graces the grand vaulted ceiling of Grand Central Terminal’s Main Concourse. The burst of this iconic color is just the start of the rich imagery used to illustrate the story of how Grand Central Terminal was saved with the help of a certain “Jackie O.”

The fight to save Grand Central Terminal is one of the most significant chapters in New York City’s historic preservation story. The Beaux-Arts Terminal, completed in 1913, quickly became the monumental gateway into “the city that never sleeps.” However, as train traffic diminished over the years, the terminal silently fell into disrepair. By the mid-20th century, the landmark structure was at risk of being lost, as architects proposed massive skyscrapers for its site. The New York Times ran a front-page story lamenting the imminent loss of “one of the most influential pieces of urban design of the twentieth century.” Former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, a native New Yorker, read this story and immediately sprang into action to save the terminal from the same fate that had befallen the magnificent Pennsylvania Station just years before. The rest, as they say, is history. When Jackie Saved Grand Central covers the legal battle that ensued, with Jackie helping to lead the charge all the way to the United States Supreme Court to stave off development and restore Grand Central Terminal to its former glory.

For a children’s book, the history used as the basis for this story is somewhat obscure for younger audiences. The book makes direct reference to the court process that Jackie and other supporters progressed through, reaching all the way to the United States Supreme Court. Though the complexity of the message might only be fully understood by older children who have already started learning about American history or the American political system, the book finds creative ways to draw in diverse age groups.

The story starts by describing Jackie as a person who simply loved history, diving headfirst into treasure hunts to find long-lost relics of the past. She is also clearly depicted as a person who loved New York City. Growing up in the Big Apple, Jackie had embarked on trains leaving from Grand Central Terminal many times. Saving the edifice, as well as disseminating its rich history, was clearly important to her on personal and professional levels alike.

The book’s illustrations, by Alexandra Boiger, also visually demonstrate the passion that Jackie had for Grand Central. At the beginning of the story, as author Wing is describing Kennedy’s time as First Lady, Jackie appears composed and courtly in black frocks and overcoats. However, just as protests ramp up to save the building, Jackie suddenly appears in a radiant red coat with stylish shades to match. Adults, who know of Jackie for her iconic and innovative style, will appreciate this imagery. Children, who may not know much about “Jackie O,” can still appreciate the sudden vibrancy that exudes from the page as Jackie jumps into the mission at hand.

The illustrations convincingly capture both the grandeur of Grand Central’s architecture and the zeal with which protestors fought for its preservation. The third spread in the book takes readers into the Main Concourse, the heart of the vast terminal complex. This illustration captures the awe-inspiring scale and majesty of the space. From the cerulean mural on the ceiling depicting the constellations to the massive golden chandeliers, it immediately becomes clear why this building was worth fighting for. Another spread shows the famous Landmark Express, which carried Jackie and fellow preservationists to the nation’s capital from Manhattan, garnering support along the way. This train exemplifies how this fight extended well beyond New York City, and served as a portent of what the future might hold nationwide as a new preservation ethic emerged.

The story does have some slight inaccuracies, such as implying that the New York City Landmarks Law was enacted as a direct reaction to the outrage surrounding the proposals for skyscrapers atop Grand Central Terminal. Though not a fatal mistake in terms of the larger preservation story, it is indeed factually remiss on this point. However, given the medium of a picture book for young audiences, Wing does a good job of portraying the significant arc of the story. The book moves from Grand Central’s majestic beginnings to its dismal deterioration, and from its narrow escape from the wrecking ball to its painstaking restoration. Wing also successfully conveys the larger lesson to be learned from the story of Grand Central: the world around us contains places, large and small, that are not only important as part of our own memories and experiences, but as part of the histories and experiences of entire communities, cities, and even the world. These are the places that we must fight to protect. And as the trains continue to arrive on time at Grand Central Terminal, so, too, will the preservationists, armed and ready for the next battle.