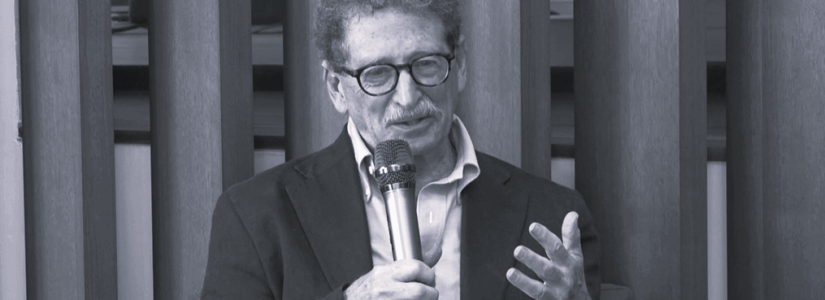

Q: Thank you and welcome to everyone, and thank you especially to the J.M. Kaplan Fund for hosting us here tonight—and I’ll thank them—graciously hosted us in the past as well. For the record and for probably the few of you in the room who don’t know me—since I believe I recognize everyone here—my name is Emily Kahn. I’m executive director of the New York Preservation Archive Project. I am also a former student and advisee of Andrew Dolkart, whom I am proud to call my mentor and also one of my favorite people in preservation and beyond. We actually have conducted an oral history with Andrew in the past as part of our Roots of LGBTQ activism series. It’s two hours long, and it’s very interactive and engaging. It’s really one of my favorite oral histories in the series as well. But we noticed that that focused a lot on his LGBTQ activism work, and we wanted to make sure we had a more general picture of Andrew Dolkart’s great accomplishments in New York City preservation over many years, so we’re very excited to have Andrew here tonight for this oral history. Andrew, would you like to start by introducing yourself—who you are, and a bit of your background of how you became involved in New York’s preservation?

Dolkart: I’m Andrew Dolkart. When people ask me what I do, I tell them I’m an architectural historian and preservationist. My background is that I grew up in Brooklyn in a progressive household, in Brooklyn. I always wanted to do something that had an impact on people. I think that in addition to all the things that Lisa [00:01:57] [Ackerman] said that I’m interested in, it’s not only the buildings and the city but it’s the people there. I always say that buildings have lives. I was one of those people that graduated from college—we both actually went to Colgate University [audience laughs]—I graduated from college, and I had no idea what I wanted to do with myself, but I had gotten interested in architecture. I was trying to figure out what to do, and I thought, well, I’ll go and get a PhD in art history. I lasted a year.

And I had this really interesting experience where I was sitting around with three colleagues at lunch, and we were talking about the difference between the beautiful, the picturesque, and the sublime. [audience laughs] Which is actually a topic that I find very interesting, but it occurred to me at some point during this that the only people that cared about this were the four of us who were sitting there and 25 other people [audience laughs] and that that was—I needed to do something else. Then somebody told me about the preservation program at Columbia. I came down and I met with Jim Fitch, and I never looked back. I was able to develop a career that combined my love of architectural history with preservation. So I went to Columbia, finished at Columbia, worked at the Landmarks Commission. By a fluke, I got a job at the Landmarks Commission the summer before I came to Columbia. By a coincidence. Then I worked for Landmarks, and then I had my own consulting business, and I was an adjunct teacher at Columbia. Then a job opened and I became a full-time professor, and here I am.

Q: It’s well known that you’re a native New Yorker—you’re from Brooklyn—but you discussed in your previous oral history with the Archive Project that you traveled extensively as a child. Did you always know you wanted to stay in New York City?

Dolkart: I did. I loved traveling, and we would go cross country every summer. It was always exciting to see places. At 11 years old, I was the one that wanted to stop at house museums. [audience laughs] I knew there was something there. [audience laughs] And I grew up in a household where going away to college was what you—what you were going to do. So, I wanted to do that—I wanted to go away—but I wanted to come back. I really fell in love—growing up, I fell in love with New York. I was of a generation where there was no such thing as a playdate; you just went out. [audience laughs] Since I grew up in the city, and after a certain age I was able to take the bus or the subway by myself, and I got out in the city. But I think that one of the key things was in college I used to shelve books in the library to make a little extra money, and one day I was shelving books and I discovered the AIA Guide, the first edition, the blue one. [audience laughs] [00:05:00] That really changed me. Because on vacations, then, I would use the AIA Guide and really started discovering New York.

Q: We discussed your childhood home in the previous oral history but what never came up was actually your current home. You talk about how preservation is about everyday buildings and everyday people, so I want to talk a bit about your every-day. Can you tell us about your current home neighborhood, please?

Dolkart: Well, I’m very lucky. I live in the most beautiful apartment complex in New York, which I can say because I’ve been on almost every block in New York. I live in this complex called Hudson View Gardens, which is this little Tudor village that overlooks the Hudson and has gardens. I live down a private drive, with beautiful gardens. I come home at night, and you inhale, and it’s just incredibly beautiful. I’m in the city but it’s so bucolic. In fact, I have a little house where I go to write in Columbia County, and I had to get used to traffic noise in the country [audience laughs] because my apartment is so quiet. But it’s in a really interesting neighborhood, a neighborhood that a lot of people who don’t live there don’t really know. Historically it’s called Fort Washington, which is the name I still use for it. The real estate industry has renamed it Hudson Heights, a name I find really offensive. [audience laughs] It’s a neighborhood of apartment houses from the 1920s and 1930s.

The speculative apartment house of the early decades of the 20th century is a building type that preservationists and historians have skipped. We’re interested in rowhouses, we’re interested in luxury apartments, and then we’re interested in modernism. And this whole kind of traditional—especially the traditional-looking ones. The deco ones, people are interested in, but the colonial ones, and the Tudor ones, and the Mediterranean ones, we’ve forgotten about. And so, it’s a really beautiful neighborhood. I call it the last of the old New York neighborhoods. Because there are no chain stores, and the shopkeepers know who you are, and it’s just a great place to live. And there is now just beginning a group that’s going to be seeking historic district designation for the area.

Q: We know that speculative housing development is one of your academic interests that you’ve researched quite extensively. Which came first, your decision to move into Washington Heights—a neighborhood with a lot of that housing type—or your decision to study speculative housing?

Dolkart: The reason that I moved into Hudson View Gardens has to do with my working as a consultant. I was hired by the people that wanted Tudor City to be a landmark district. I wrote a report on Tudor City; I did a lot of research on Tudor City. The question that I always ask—I like to ask—is I always want to know why. I wanted to know why the Tudor, and I got really interested in researching Tudor and all the social meanings of Tudor in the 1920s. I found an article about Hudson View Gardens, and I—I believe in—I still do this—I Xerox every article or print out every article that I see that might be of interest in the future. And I had it. Then when we decided we were going to buy a coop somewhere, I said, “Oh, I know this really—this place looks really interesting. It was built in 1924. It’s always been a coop.” We went up, and then the next day we bought an apartment. So, I was already interested in the kind of vernaculars of the 1920’s architecture, and that sent me up there!

Q: How would you say your academic experience as a student in Columbia’s preservation program changed your perception of your home city?

Dolkart: One of the great things about Columbia when I was there was that there was a lot of freedom in deciding what you wanted to do. There were required courses, but I was able to really focus on New York. I started giving walking tours at that time. I was able to do a thesis on—my thesis was on Protestant church architecture in Brooklyn. I was working at the Landmarks Commission as a student at that time, too, and we were working on a survey, so I spent time surveying in the Bronx. This was the time when the Bronx was at its low point. It was, to this day, the most depressing thing I’ve done in my life, was being part of that Bronx survey. But it did get me out to see the places in New York that I did not know. I knew Brooklyn really well and I knew Manhattan, but I was learning about other places, too. [00:10:03] That was really important.

Q: Can you talk a bit more about how your interest in sacred places developed?

Dolkart: I got interested in sacred places because to me, they tell us something about who the people were by the time they were built, and then if you trace sacred spaces you can see how neighborhoods change. I see sacred places as the anchors of helping to understand a neighborhood. I think there were really great examples. If you look at Harlem—look at Lenox Avenue south of 125th Street, which is lined with these really grand religious institutions—there are like four churches and a synagogue. They tell us something about the first generation of people that lived there. There are Protestant churches that were built in the 1880s and early [18]90s, and then a German Jewish synagogue comes in. And then, to trace how they changed, how those congregations changed from Dutch Reformed Church to Seventh-day Adventist Church, tells us about what’s happening in the neighborhood. It’s such a good way to understand neighborhood change and neighborhood evolution.

Also, of course, they were what people invested money in. And so, they are distinctive, unique buildings in any neighborhood, and I think that they reflect a lot about pride in the neighborhood. In the Mount Morris area, in Harlem, there are beautiful rowhouses but they were almost all built on speculation, so they reflect what developers thought people wanted. Whereas the sacred spaces reflect what they actually wanted. So I find them—they’re a very complex building type that tells us—from which we can learn a lot.

Q: What would you say are some highlights from your time of working for the Landmarks Preservation Commission?

Dolkart: When I worked at the Landmarks Commission, the staff had a lot of input, which is a lot less the case now. We were doing surveys. We did a Bronx survey. We did a Brooklyn survey as well. And the staff could nominate buildings. So I was able to get a lot of religious institutions nominated. I also was very interested in the suburbanization of Flatbush, which was something that I had worked on as a graduate school student. So I was able to persuade the—present to the commission Prospect Park South and Ditmas Park and get them interested in that. And as I was just telling Michael, one of my former students who was here who lives in Clinton Hill—that I was so determined to get Clinton Hill designated as a historic district that when it happened, I said, okay, now I can leave the Landmarks Commission. [audience laughs] Prospect Park South and Clinton Hill were the two things that I really wanted to see.

But I just—sometimes I see something that—a building that I persuaded the Landmarks Commission to designate, or to at least hold the public hearing on, and good things are happening. One of my absolute favorite buildings, a building that I bet very few of you know, is the Edgehill Church at Spuyten Duyvil. It’s this tiny little church in the Southwest Bronx, in Spuyten Duyvil. It’s this sort of arts and crafts Tudor building, very funky design, by Francis Kimball, one of my favorite architects. It had very little—very small congregation when we did it, and then it was vacant for a while, and now the Spuyten Duyvil Historical Society is taking it over and is restoring it. So it’s great to see that this building survives because it’s a landmark, and that maybe I had a small bit in getting it designated. It makes you feel good.

Q: Clearly you’ve had a lot of great preservation successes. I do want to take a moment and talk about, are there examples from your time at the LPC or beyond of buildings or districts that were not designated that have really resonated with you throughout the years?

Dolkart: Oh, that’s a good question. I think there were two projects that I worked on that we lost that I am very disappointed about. One is the Guggenheim addition. To this day I think it’s the worst thing that’s happened to architecture in New York in my life—that the Guggenheim Museum, which used to be this freestanding, dynamic swirling building now has an armature that holds it up, and it completely changes Wright’s vision of what that museum should be. Every time I see it, I—I—I—I hate it. I found there is one spot where you can stand on the west side of Fifth Avenue and not see it. [audience laughs] Where you can still see Wright’s vision. [00:15:02] That, and the other one is an obscure thing that I worked on which was called The Cottages. The Cottages was this two-story complex on—Second Avenue or Third?

Person: Third Avenue.

Person: Third, third.

Dolkart: On Third Avenue, that was built under the El. It was built in the [19]30s, on Third Avenue. It had brick and glass block. And it looked like, you know—it was nice, but it didn’t look like a lot. But in the back, it was this incredible garden complex, of housing, of small apartments that were stepped up on terraces and looked out on this garden. It was so beautiful and so different from everything else in New York. I believe it was heard but rejected. It saddens me that that’s gone. Because it was so—it was unusual. A lot of New York is very predictable. I don’t mean that in a bad way, because I love the vernaculars of New York. That’s what I spend most of my time researching. But sometimes you see something that’s so different and so eccentric that it just makes you smile. And it’s sad that it’s gone.

Q: Yeah, but I think it’s important that we still talk about it, and that means that the story will be remembered. We at the Archive Project I find often talk about quote-unquote “preservation failures” in addition to successes. So, it’s important to hear that this still weighs on you even years later. Transitioning to the vernacular, I know you are a big advocate for cultural heritage and preserving the vernacular. Can you talk about how you have advocated for this type of heritage and why you believe this is important to preserve?

Dolkart: When I started in preservation I don’t think I really understood much about the vernacular or about cultural preservation. I was interested in like high-style churches and synagogues. But as I learned more and more, I really came to focus on the fact that what makes a place, what gives a place character, are the everyday buildings that we walk by and maybe we don’t even notice. But they’re the building type of any place. I must have first noticed this when I got involved with the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. I’ve been involved with them as a historian since the day after they discovered the building that they currently occupy at 97 Orchard Street. I was consulting at that time and I got a call from one of the founders, who were explaining that they wanted to establish a tenement museum and they needed somebody to write a history of this building that they had found, and would I come down and take a look at it. So, after I yawned, thinking, wow, that is like the most boring thing I can think of, [audience laughs] I said, “Okay.” Because you know, when you’re doing consulting, you don’t say, “No.” [audience laughs] Unless, you know, they want you to advocate for demolishing the building or something like that.

And so I went down, and the day I walked into the building that is now the Tenement Museum really changed my life. Just to be able to stand in this building that was in ruinous condition and get a feel for the lives that had been lived in this building. My grandparents had lived on the Lower East Side, and suddenly—it was so powerful to be there. Then I undertook the research and then eventually did a book. In fact, I’ve just finished a revised third edition of the book which will be out in a few months. It changed my focus and my understanding of the city. Since then I’ve become interested in speculative apartment houses, garment lofts, all these other kinds of vernacular buildings that are so defining of what New York is. There are similar types of buildings everywhere that you go, that give character. I love London, and London has its own vernaculars. It’s true of every place.

Q: The Tenement Museum is one of my favorite museums in New York City. I grew up going there. I’ve been on your tour of the Tenement Museum. They’re even one of our grantees for the Shelby White & Leon Levy Archival Assistance grants. Oftentimes when I mention this museum, we manage to get back to Andrew Dolkart very quickly. [audience laughs] Can you talk a bit more about your role in establishing this really important place in New York City today?

Dolkart: Yeah, I did all the initial research on the building, and I would say that the building is the Tenement Museum’s most important artifact. I think that for me, what’s so important about the Tenement Museum is how unimportant the Tenement Museum’s building is, in a sense. [00:20:00] It’s an everyday tenement. People—most importantly my Columbia colleague Richard Plunz—had written books about housing, and so the housing laws were known. The big picture was known. But what I think is so important about the Tenement Museum is how it looks at the minutiae, at the little things, at the way people lived and how they lived. And how the building evolved over time, and how the laws impacted—the laws people know about, but how did they impact on new buildings, and how did they impact on forcing changes to be made on previously built buildings.

Q: Research is endless! I think it’s really interesting that you’re one of honestly a few people in this room and plenty of people who went through the Columbia program as a student and is now a professor. How would you say the program has changed or even preservation education has changed?

Dolkart: It has changed a lot, but I think it still has some of the foundations that Jim Fitch established. The notion that preservation was not one thing, and that it wasn’t only for architects. In Europe, most preservation education is for architects. That it was for planners and historians and architects and scientists—I think that that is still very much a part of preservation education in America, the idea of educating students in all these different aspects, so that they can maybe specialize in something but they’re familiar with it.

But it has changed a lot. There is, in preservation education and preservation in general, a lot more interest in cultural issues, not just in bricks and mortar. I think that’s a really significant change that has occurred in my lifetime. There is, of course, a lot more interest in issues of diversity, and this has been an issue where preservation lagged, I think, for a while, but I think is catching up. Now of course there’s a lot of interest in how preservationAlthough all this study is of one building, I think it speaks for a whole building type and the hundreds of thousands of people who lived in these buildings. And I think that the fact that it’s not just the four walls of the building but it’s the thousands of people that moved through 97 Orchard Street over time that make it such a powerful thing. I think one of the things that I argued for very strongly was that they should keep some of the ruined spaces, that they shouldn’t restore every space or turn every space into a museum room. I think that that allows people to come and bring with them any stories that they might have.

I remember a colleague, Donna Gabaccia, who is a historian of Italian history, and who at the time was teaching in New York. She said to me that—“That’s great, but just remember that my grandparents didn’t live like that.” I think that that’s true, to have the balance of seeing the ruin where the building has had lives and then being able to go into the restored apartment that talks about an Italian family and the experience that they had. Also the fact that they interpret the lives of real people, most of whom lived in the building, I think is why, where so many house museums have declining visitation, the Tenement Museum has enormous visitation.

Q: You’re a historian, and I think equally importantly you are someone who teaches the next generation of historians and preservationists how to research New York City. Your guide on how to research New York City is still something I consult on a regular basis. You mentioned the thousands of stories of people who lived in the tenements. How would you recommend that people choose which stories are told in places like the Tenement Museum?

Dolkart: Just today I updated my Hints on Researching New York City Buildings [00:23:00] research on New York. I think that a lot depends on what it is and what your ultimate goal is. I love the fact that the Tenement Museum interprets the lives of real people, that they’re not making up stories from whole cloth. Now of course they’re making up some aspects of the stories from research. I think that that’s important, to look for evidence of—first of all, to understand the building. For me, buildings have power. So I think you have to understand the building. I think that that’s crucial. And the neighborhood that the building—and the environment the building is located in. But then to tell real stories about the building. This is why not only at the Tenement Museum but what I think that the LGBT Historic Sites Project does successfully is that we look at extant buildings. Because for me and for I think most of us in this room, and for people that are interested in preservation, buildings have power. I think it’s crucial to get people to understand what that power is. That they might walk by a building every day and not realize why it’s significant. That, oh, it’s just a tenement, or it’s just a rowhouse, or it’s just a garment loft. But what does it tell us about who we are, where we’ve been, where we’re going I think are things that are really, really important.

Q: I’m really thrilled that in this room are people who are professors in Columbia’s program as well as people who were students at the same time that I was at Columbia. At least in my cohort, we played a game [unclear] [00:24:54] the project of, how long does it take to get to Andrew Dolkart when researching New York City buildings? [audience laughs] The answer was never more than five minutes [audience laughs] or three clicks on Wikipedia. [00:25:05] It was really quite astounding how big of an impact you’ve had in your research and your writing. I just want to know, what do you love about researching New York? Why do you continue to research New York so extensively?

Dolkart: Well, because there’s always something to learn here. You can never exhaust the interests and the topics that are out there. Every day I see a new building or I see a building in a different light, or I’m researching and I find something completely new, even though I thought I knew it pretty well. And I think that’s why. I mean, it’s just—New York is just forever fascinating. And I have enough book ideas in my head for multiple lives. [audience laughs]

Q: What is your current research fixation?

Dolkart: Well, no, for way too long I’ve been writing a book on the architecture of the garment industry. I made a little progress this summer. It’s all researched but I haven’t gotten the chunk of time to write it. So I hope to get that done. Because that’s a vernacular building type that—scratch [unclear] [00:26:16] any Native New Yorker and some ancestor had something to do with the garment industry. Whether it was Jewish or Italian or Greek or Puerto Rican or Black garment workers, or the old Knickerbocker families that ran the fabric trades, there’s some story there. But I want to do something on speculative apartment houses of the [19]20s and the ‘30s. I toyed with an idea of maybe not doing a book on speculative apartment houses but doing a book on vernacular housing in the 20th century and just having chapters on the different kinds of apartment houses and other building types. That’s what I’m kind of thinking about now.

Q: In our game of how long does it take to get to Andrew Dolkart, we would come up with countless National Register nominations. I want to know, do you still feel that National Register listing and landmark designations are some of the best tools that we have in preserving the built environment?

Dolkart: Well, I do, in part because we haven’t really come up with too many other successful tools. I do think landmarking is really important because it is a legal mechanism. When something is landmarked, you should be assured that it’s going to be preserved. Now, of course a lot depends on the strength or weakness of the Landmarks Commission, and at the moment I think the Landmarks Commission is not as strong as it has been in the past. I do think that’s important, but I don’t think it’s the only thing. National Register nominations are great, sometimes just because it’s really good PR and you can use it as a really strong argument for preservation. But also tax credits because you’re on the National Register have saved a lot of buildings. Now there are a lot of National Register nominations being done for public housing in New York, and they’re going for tax credits. I think that that’s great. They don’t all have to be landmarks. But I do wish that there were more things.

I do think that public recognition is really important, so that people understand their environment. That’s what the LGBT Sites Project does. We have like almost 500 sites now, but they’re not all landmarkable or National Register eligible. I’m advising—and actually Emily is going to be a reader on a thesis that’s being done now on sites of significance in the history of the fight for abortion rights in New York. Most of these aren’t landmarkable sites, but for the public to know that these everyday, vernacular buildings have a rich history I think is really important. So I think recognition is important. But I don’t want to dismiss the idea of landmarking. I wish we were doing more of it.

Q: What do you think recognition could look like beyond landmarking or a National Register listing?

Dolkart: I think websites are really great. I personally do not do social media, because my life is—life is too short. [laughs] I have trouble keeping up with email. But I do understand the value of it. I think that the internet, the web, allows for so much information to be out there to help us understand the city and to recognize places. [00:30:06] I think that these are really positive developments.

Q: You talked about, in our previous oral history, your transition to becoming a professor. Your previous oral history with us was in 2019, so about five years have passed now. I want to know, how do you balance your life as a professor, an active scholar writing books, and as a practitioner still doing work in the field?

Dolkart: Well, it’s hard. [audience laughs] Especially when—in the fall semester I teach a studio, and that’s very time consuming, but in the spring I don’t. I say, oh, this is going to be such an easy semester. I’ll have lots of time to do other things. Then somehow all your time gets filled up with things at school, so you don’t have as much time. But I do feel that at least for me, it’s really important to be involved in preservation. I don’t think preservation is an ivory tower field. I don’t think professors of preservation should only be doing academic work. I mean, preservation is a field where you have to be out there. People are out there in different ways. People are activists in different ways or historians in different ways. But for me, it’s really important that I’m involved with organizations, and I try to find the time for it. If you care enough about it, you’ll find the time for it. That’s why my Garment Center book isn’t written because [audience laughs] there’s other things that get in the way of that.

Q: Do you remember I helped you work on the garment book my first semester?

Dolkart: I remember. And students going back farther! [audience laughs]. I didn’t think it would take so long, and I’ve forgotten the names of the students who helped me [audience laughs], so I’m going to be embarrassed when all the acknowledgements aren’t as complete as they should be.

and climate overlap with one another. That’s not a specialty for me, but it’s a crucial, crucial issue for the future. Just yesterday in American Architecture we were talking about the first half of the 18th century, and I showed a neighborhood in Newport, The Point, which is probably the best concentration of 18th century vernacular houses from the early 18th century. And it’s right at sea level. It’s not going to be there in 30 or 40 years! What do we do with a neighborhood like that? How do we deal with that? So even from the historian’s point of view, the climate issues are really crucial. I think those are some ways we’ve changed. And stayed the same.

Q: A question that I have, and a question that also a couple people submitted, is what’s some advice you have for people who are interested in getting involved with preservation?

Dolkart: Well, it’s getting involved. [audience laughs] You can’t do preservation by just sitting in your house. [00:35:01] You have to get involved. You have to get involved with preservation groups, neighborhood groups. If there isn’t one, help establish one. Just like somebody called me up a few months ago and said, “I’m really interested in a historic district in Fort Washington. We’re interested in getting involved with a community group.” And so I said—yeah, so did Emily; she’s on this committee too. So I think that the most important thing is to get involved. You can get involved in lots of different ways. You can get involved quietly behind the scenes. You can get involved by being a loud New York activist. [audience laughs] You know, all good! But I think that for people—preservation is a community activity, and that’s really important. Even if you’re a research hermit, like I tend to be sometimes, you’re doing it because you’re involved and because what you’re finding and producing is being used for advocating for preservation.

Q: We could talk for hours, but I do want to leave time for something very rare in the oral history world, which is a live Q&A session. I am going to hand the mic over to Tony Wood, founder of the Archive Project.

Anthony C. Wood: Andrew, to the current generation of young preservationists, you’re probably best known for your advocacy on LGBT sites, but for decades you’ve been the go-to person for any effort, any advocacy effort, providing the intellectual capital whether it was City and Suburban, the Lalique windows, all of those great things. You’ve ended up working very closely with some of those advocates, passionate people. I’m just curious any kind of insights you had—what were your favorite? Is there a favorite advocacy battle that you were involved with, and was there one of those wonderful, wild, crazy preservation maniacally focused advocates who has left a pleasant memory with you?

Dolkart: Because I’m a native New Yorker, I can work with all these—crazy New Yorkers. I worked with Arlene Simon and Betty Wallerstein and all these great neighborhood people. Sometimes they can drive you crazy, but ultimately they’re doing great stuff. So that’s good. You asked also something that really—I don’t remember the wording—that made me really proud of what I did. Well, the Lalique windows are the best thing. I don’t know if you—everybody may not know this—on Fifth Avenue, between 54th and 55th on the west side of the street, where Rizzoli Bookstore was once and on the same block with the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, there was a completely rundown, going out of business, rip-off-the-tourists building. It had been purchased by a developer, and the MAS was interested in trying to save Fifth Avenue, and they asked me to research whatever I wanted on Fifth Avenue.

I had always noticed by looking up—because I always look up—that there was these incredibly dirty, grungy windows that looked really interesting. They were three-dimensional. One floor was occupied. I went in, and they were fantastic from the inside. I started researching them and they turned out to be the only Lalique storefront in America. It got leaked to the press, and lo and behold, Landmarks, which had said they were not going to hold a public hearing on these buildings, changed their mind. And they were designated. For a long time, it was the front façade of Bendel’s. Now it’s for rent. Every time I see those it makes me smile, that they’re there because of something I discovered. It makes you feel good!

Q: Andrew also talks about those extensively in our previous oral history, too, with the same level of joy and pride as well. It’s really great to see that that’s carried through.

Raymond Kahn: As a former Wall Street guy, I’m sorry I have to ask this, but you used the term, I believe, “speculative housing.” I’m guessing that—can you define that for me? Because I think it’s probably different than what I define as speculative housing.

Dolkart: Well, most of New York is built up by what I would call speculative housing, which was put up by speculative builders whom I think were no different from speculative builders today; they invested money in building to make a profit. [00:40:03] But speculative housing didn’t mean cheap housing; it meant that you were building housing for what the market would bear. If you were building middle-class rowhouses in Clinton Hill or Bedford-Stuyvesant but you built in the mid 19th century, you built with a brownstone front and a high stoop because that’s what was going to sell. If you were a speculative builder of apartment buildings for the lower middle class, you built five- and six-story buildings with modest apartments but with amenities in them and that would rent to people. But it was always profit-making housing. Or other kinds of buildings.

New York is made up—over 90 percent of New York is speculative buildings: speculative office buildings, speculative housing, speculative garment lofts. And so that’s what I mean. I think speculative builders maybe financed in a way that’s very different today, but ultimately they’re building to make a profit. I think that it’s similar. If you had asked the speculative builder who put up the brownstone rowhouses on South Portland Avenue in Fort Greene whether he thought that 150 years after they were built they would be beloved and a historic district, he would have laughed at you [audience laughs] because that was not his intention. He was intending to build buildings that could sell at a profit for, in that case, an upper middle class market. I think that’s what speculative builders always do. I think we should appreciate that we are a city of speculative building and not denigrate the idea of speculative building.

Matt Dellinger: I’ve got a question in that vein, actually. Oftentimes the enemy of preservation is the new speculative building. So, how do we judge when to choose the moment of preservation, that this is what’s to be preserved, not what came before it and not what’s going to come after it?

Dolkart: I don’t think in the broad brush that the speculative building is the enemy of preservation. It just depends where it is. I’m not opposed to new construction. There are lots of places where new construction is great. But I think that we need to consider more, as we’re doing rezoning or as we’re doing other proposals to change, to look at what is valuable that is there and try to preserve that. Because I think that one thing that we have learned—this was a mantra when I got involved—with Carol Clark here, who was in my class at Columbia—was that the new and the old mix well together, and that that makes for a dynamic city. I think that the most dynamic neighborhoods have that mix of the new and old.

So I’m not opposed to tall buildings; just I’m not in favor of tall buildings everywhere. I’m not opposed to new construction. I think that makes a dynamic city. I love the fact that I can go away for two months and come back and my neighborhood has changed. [audience laughs] We live in a dynamic city, and that’s why we want to live in New York. I go to too many cities that—we’re not Toledo, Ohio, where—I’m on a campaign to visit all the art museums of American [audience laughs]. I did all the industrial towns of Ohio a couple of summers ago, and Toledo was the most depressing place I’ve ever been. We’re not Toledo, and that’s great. I mean, not for Toledo [audience laughs] but we’re dynamic and we’re changing, and people want to invest money here and build. To have the new and the old together is what makes New York an exciting place.

Adrian Untermyer: Andrew, thank you. Emily, thank you. As we look to cement future victories, what do some of the successful preservation campaigns over time have in common?

Dolkart: That was one that would probably need a little bit more thought, but I would say that it was neighborhood support, this idea of a community fighting for something vocally, is what has been successful. I think that’s really important. Sometimes one person can send in a letter to the Landmarks Commission and say, “Oh, you should designate this,” and they will, but that doesn’t happen very often anymore. [00:45:01] That used to happen—that anybody could just send in a request or a letter, and Landmarks might act on it. But I think that a community working together, and not only the citizens of the community but working with their political officials—I think that’s really, really crucial. This is a place where I think that the preservation community has not been successful. Especially with the city council changing over, members changing over regularly, we haven’t been out there meeting with them all and getting them interested in preservation. I know the Landmarks Conservancy used to do that, but not so much anymore. There are preservationists who are really great at that, at going and sitting down with politicians and talking with them. We need to get that support as well as the everyday—the people of the community to do it. Because otherwise, why is anybody going to listen to us?

Françoise Bollack: I just want to thank you for remembering The Cottages, which was like a real loss, I think. If one is interested in housing—and I hate this term “housing” because it projects such an institutional sort of thing—what was interesting about The Cottages was that it was a really inventive housing form. It was commercial on the avenue and it was this Georgian revival paradise on the back. I think it would be interesting to [unclear] [00:46:43]—this is not going to be a question [audience laughs]. Since you are interested in housing, I think it would be interesting for preservationists to try and make a catalog of the large quantity of really inventive housing forms we have in New York City. I’m thinking, for example, about the Charlotte Brontë houses, which are locked down [unclear] [00:47:09] which are an apartment building that masquerades as a big house. I think that there were a lot of very inventive housing solutions in New York City which I think have gone unrecognized, and I think it would be interesting for the preservation movement to be interested in this in the context of our attempt to create more housing. Because I think we tend to just think about a certain model, and I think that preservationists have something to offer to this problem.

Dolkart: I think that you’re right that there’s a lot of really interesting and creative housing. Amalgamated housing, both on the Lower East Side and in the Bronx, neither one of them has been the subject of much preservation interest. There are a lot of what I call low-income coops, these labor coops that were very much involved with socialist politics, that have not been looked at. But I also think—and I know that you’re particularly interested in this, Françoise—is low-income housing projects and tower-in-the-park projects. It’s time for us to reevaluate—some of the things that many people of my generation got involved in preservation to stop are now maybe more interesting. Last year we did—our studio last fall focused mostly on postwar office buildings in Midtown, and buildings that I’ve always really disliked turned out to be fascinating! [audience laughs] I had not really reevaluated them since the time when they were relatively new, and now it’s the time for us to just start doing that. Not only in housing but in many other kinds of buildings, there’s a lot that’s interesting out there that we haven’t recognized as well as we should.

Michael Devonshire: A very personal question. Andrew Dolkart is doing research on worker housing in the mid 19th century and he comes across a book that has vernacular bank buildings in Staten Island. What keeps you from going down the rabbit hole? [audience laughs]

Dolkart: Well, that’s a problem we might—we all love going down the rabbit hole. I do go down the rabbit hole frequently. That’s why I try to save—

Michael Devonshire: How do you stop it?

Dolkart: I try to just save all these things, so that in case I need to write something about banks in Staten Island, I’ve got some of that information handy. But it’s hard. And I have to say—and I’m sure I’m not the only person that impacted on this—my first major book was Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture and Development. [00:50:05] I basically wrote that over two summers. Because I just sat there with all my Xeroxes and I wrote. There was no internet. There was nothing to get in my way. [audience laughs] Now, you sit down to write and you write one sentence and then you’re looking stuff up on the internet, and like, four hours later, you [audience laughs] haven’t written another word! [audience laughs] Sometimes I think maybe it would be good to shut myself off in a cabin somewhere [audience laughs] with a 60-watt bulb and that’s it. [audience laughs]

Q: Thank you all for joining us for this live oral history with Andrew Dolkart. Thanks again to the J.M. Kaplan Fund for hosting us here tonight and to Coco Nelson, our brand-new administrative coordinator who has been really instrumental in getting this together. As with all of our oral histories, this will be transcribed and uploaded onto our website.

[audience applause]

[END OF INTERVIEW]