Elizabeth Ashby

A tireless advocate for preserving the Upper East Side, Elizabeth Ashby has worked to expand the Upper East Side historic districts and is the co-founder of Defenders of the Historic Upper East Side.

Elizabeth Ashby has been an activist for preservation on the Upper East Side for decades. She was named president of Carnegie Hill Neighbors in 1983, and began being much more active in local preservation and zoning politics. She advocated for the Sliver Law, a zoning code that regulates the height of narrow residential buildings and helped to expand the Carnegie Hill Historic District. Under her leadership, the Carnegie Hill Neighbors published the Carnegie Hill Architectural Guide. She also co-founded the Defenders of the Historic Upper East with Teri Slater in 2003, participating in the fight against Renzo Piano’s expansion of The Whitney Museum of American Art. She speaks about how critical it is to educate the community about what landmarking is and how it applies to people’s properties, and the importance of enforcing the rules within districts to preserving the history of an area.

Elizabeth Ashby, Session 1

Q: All right. So we’re going to try this. My name is Owen Doherty and I am interviewing Elizabeth Ashby for the New York Preservation Archive Project. And it is March 29th, 2012. I was curious because in doing research on all the work that you’ve done I didn’t find a lot about you yourself. I was wondering how long you have lived in the neighborhood.

Ashby: I’ve lived here since 1979.

Q: Oh, okay. So were you part of the initial founding of Carnegie [Hill] Neighbors?

Ashby: No. I took it over—I was the third president. I think it had been very active under someone called Fred Papert who moved away I think in—before I moved here in ’78 or something like that. Then it had a very quiet caretaker period. It had a very good program plotting the Park Avenue malls, but wasn’t doing anything else between that time. And then I took it over in 1983.

Q: And what motivated you to move to this neighborhood? Were you already familiar with its history or—?

Ashby: No. No. No, not at all.

Q: Were you just drawn to the architecture?

Ashby: I had lived in London for twenty-four years so I had never lived in my own country as an adult. My brother and sister lived around here so I thought I’d start out here and see how I liked it. And, I don’t know, one thing led to another and I bought the apartment, because I thought I’d rent one, but there really wasn’t much to rent, so I bought one. Thirty odd years later here I am [laughs].

Q: So you said that when you became president of Neighbors that there were in a sort of caretaker period.

Ashby: Yeah.

Q: Was that most of what they were doing was the quality of life?

Ashby: Just the malls.

Q: Just the malls.

Ashby: Yes.

Q: So they weren’t involved yet.

Ashby: They weren’t active. They had been under Papert, but except for the malls, which is a big program. That was run by someone called Jerry Anderson. They weren’t active. I didn’t know how inactive they were until I became president and then, you know, we got going.

Q: Did you have any involvement with their projects before you became president?

Ashby: No. When I moved in here, the Stanley Isaacs house—which is a little house between the Livingston house [John B. Trevor House] and the old apartment building on the corner—was bought and they were building a sliver, which was then legal. I thought, coming from London that’s not possible, you can’t do that. Well they could. So I went to the Community Board—

Q: And for people who might not know a sliver is a very tall residential tower.

Ashby: It’s a tall building on a narrow site. So I went to the Community Board, talked to some people, and said, “Why isn’t there a law against that?” So the Community Board said, “Well, propose one.” So I did. We finally got that and that was why I think they asked me to take over Carnegie Hill Neighbors.

Q: So you were able to get change in the zoning for the area to prevent the slivers from being built there.

Ashby: Yeah, it’s called the Sliver—I mean, it’s not really called the Sliver Law [New York City Zoning Code section 23-692], but it’s known as the Sliver Law. Yes.

Q: And they just asked you to become the next president.

Ashby: Yes. I mean it was dormant enough that there wasn’t anybody to vote for it. There were only three people involved.

Q: And now there is much more neighborhood support for it.

Ashby: Oh, yes. We started—we did a lot with preservation. Before I became president, I was involved with the block association, which—I was just sitting there and they said, can you be the vice-president of the block association? To protect what we had because that building, the [Lucy Drexel] Dahlgren House, was not protected, although it should have been an individual landmark. The other one was, which is virtually its pair. With somebody called Harriet Bachman over on 95th Street, we started working on getting the tiny, little historic district enlarged. And then when I became president of Carnegie Hill Neighbors we continued that.

Q: And how did you, I guess—because I did read that you had volunteers who helped you do the research—

Ashby: Yes. As we sort of asked around and got people involved and so on. People did all the research. We did a survey, took all the photographs, had Andrew [S.] Dolkart make a report, and kept lobbying. Finally they got round to designating it, I think around December ’93. So that was twelve and a half years.

Q: Yeah. Did you yourself reach out to Andrew Dolkart to work on the report? What motivated you to work with him? Aside from the fact that he’s—

Ashby: Well, we knew about him and I think he’s excellent. Are you in his program—no, he’s up at Columbia [University].

Q: He’s up at Columbia. I’m at Pratt [Institute]. I’ve read the many a report authored by Mr. Dolkart.

Ashby: Yes. So that was how we did it. We got a lot of volunteer photographers, and volunteer researchers, and then we made the first Carnegie Hill Architectural Guide and published that. Tried to protect what we had.

Q: Do you know if—in 1990 they did change some of the rules for the [New York City] Landmarks Preservation Commission. Do you have any influence to making it easier or harder to get your district expanded?

Ashby: No, I don’t think so. It’s always hard. Because when—oh, like about 1990, I proposed the Hardenberg/Rhinelander [Historic District] and that took very little time because there were only six buildings and they were all by the same architect for the same developer. So that was quite easy.

Q: Are there any factors that you’ve found make it easier to get a designation or an expansion? Something like particularly a famous architect or—?

Ashby: Yes.

Q: Is it easier to get an individual designation, in your experience, than it is to get a district?

Ashby: Probably to get an individual because it’s obviously much less work for everybody.

Q: Was there anything that was lost or altered in the neighborhood while you were trying to get the designation?

Ashby: Yes, I think the worst alterations are the window changes on the apartment buildings. The pre-war buildings get so much of their texture from the multi-pane double-hung windows. That building across the street, those are all replacement windows and I think that’s a superb job. But most of them—I mean, we’re lucky if they go to one over one, and usually those miserable single pane tilt and turn, which were totally inappropriate. So that was the loss. I don’t know that we lost many buildings of value or any. I mean, we lost the Stanley Isaacs House for that sliver building, but that was before the Sliver Law and before the designation.

Q: Were you able to maintain support over that long period of time with the businesses and residents [crosstalk]—

Ashby: Yes, I think people were—

Q: —before the expansion [unclear]?

Ashby: Yes. We restarted the newsletter and we always had something about historic preservation in it.

Q: It’s sort of rare, it seems like Carnegie Hill Neighbors does some functions that in other neighborhoods are done by a sort of business improvement districts or smaller neighborhood associations, a combination of preservation and a sort of quality of life issues that you address, is less common.

Ashby: Yes.

Q: Was that intentional from the beginning or is that a combination you solidified in the 1980s?

Ashby: When I took it over, I said, “What is it supposed to do?” And they said, “It’s what you make of it.” We continued what I was doing of course with historic preservation and zoning. Let’s see, I forget how it started, but we started the tree pruning program and so on, and then the beginnings of a street cleaning program. Then in the early ‘90s when crime was so terrible, we started the patrol car program.

Q: And is that still going on today?

Ashby: Yes. I’m pretty sure it is.

Q: And that’s private security?

Ashby: Yes. We had patrol cars going around the neighborhood in the evening and overnight.

Q: And you also have a graffiti removal—?

Ashby: Excuse me?

Q: A graffiti removal program that was started?

Ashby: Yes, that was started—that’s an excellent idea. That was started after I left and we tried—when I was there, we tried to encourage building owners to get it off because except for stone which is very difficult, you can get it off a mailbox or a lamp post quite easily. You get it off with acetone, which is nothing more than nail polish remover.

Q: When did you join the Landmarks Commission? Do you want to answer your phone?

Ashby: Yeah, I think I better check.

[INTERRUPTION]

Q: Before you became president of the Carnegie Hill Neighbors, were you involved with any other preservation efforts?

Ashby: Well, except for the block association.

Q: In different parts of the city, were you involved with preservation more broadly or were you really focused on this neighborhood?

Ashby: Well, it really started out here, but only in support of other groups not—you know, I never took any initiative.

Q: I’ve seen you quoted a great deal in support of other people’s efforts, so I was curious how that came about.

Ashby: Oh, yeah. I think we help each other.

Q: And when did you join the Landmarks Committee of [Manhattan] Community Board 8?

Ashby: Oh, I think in the early ‘90s I guess. Somewhere around there.

Q: And I’ve noticed that you have a lot of requests. They seem to come in on a regular basis. Are there more now than there used to be for people to—?

Ashby: No. I think there are less usually now. I think that the one good thing about a recession is that people don’t have the money to do bad things.

Q: That’s true. Are you also finding that now that the district has been designated for a long time that the people who move here are more inclined to respect that designation or do you find that they’re still interested in making a lot of changes?

Ashby: I think that they’ve seen the value of it because over the years, everybody’s neighbor has tried something awful and there is nothing to convert you to historic preservation more strongly than your neighbor wanting to add ten stories or do something of that nature.

Q: And how much success or how many problems have you had with some of the requests like curb cuts that sometimes get overruled and allowed by the city?

Ashby: I think the commission now is fairly accommodating with [unclear]. I think there have been commissions and commissioners who were stronger on preservation and I think there are commissioners and commissions that are much more accommodating, and I think now is a fairly accommodating time.

Q: There have been some controversies in the neighborhood that you’ve commented on I guess in the last decade. What do you feel you’ve had the most success in pushing back against? I guess what would you think recently is your greatest success?

Ashby: Well, we fought that elliptical glass tower that Norman Foster proposed over the Parke-Bernet building and that’s been turned down. They’ve approved something that’s not right, but the developer is still trying to get the zoning changed to allow him to build it so that’s in limbo somewhere.

Q: The one that went from the elliptical tower off to one side to the glass and copper vertical—?

Ashby: Yes. With the venetian blinds all over it.

Q: Yes.

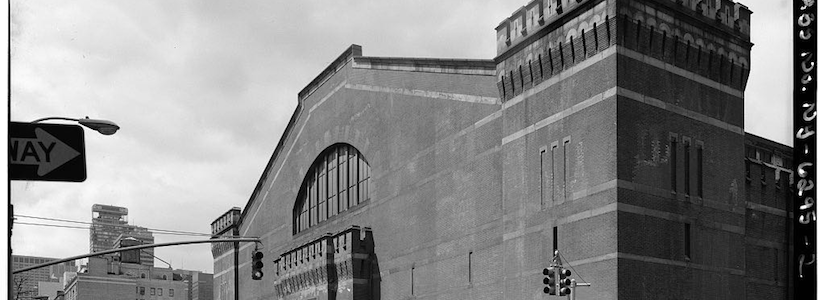

Ashby: And they finally approved something the size of the Parke-Bernet [Galleries] building, so that war is going on. The war to preserve the integrity of the—if you bark—the integrity of the Seventh Regiment Armory, because they want to put—

Q: Oh, the Herzog [and] de Meuron project [dog barking].

Ashby: Is it? What was that?

Q: The Hertzog de Meuron project for the Armory. They’ve been working on the inside but also working on the outside.

Ashby: They had a proposal and that was before Hertzog and de Meuron proposed doing their restoration. And it’s still a part of their plans, they haven’t filed the proposal for it, is to cut doorways on the north and south facades. That’s a sloping site so they have stairways. We’re still trying to make sure that they don’t do that because it’s totally out of character with the Armory, which is such a significant building. I mean armories are supposed to have the keep-out look you know, they’re based on castles and not the here-are-my-stairs-come-through-my-door look. So I’m hoping that that doesn’t come forward. I mean, it’s part of their plans, but it’s not part of their submissions yet.

Q: And what did you think of the work that’s been done so far on the interior? Have you seen it?

Ashby: I think they’ve done a very, very good job. It was an awful mess. I used to play tennis there. And that was the state’s fault because the state controlled it. They certainly let it go to rack and ruin. The state took in a great deal more money from the Armory then they ever put back into it.

Q: How often—[dog barking]

Ashby: Sorry.

Q: You and Teri Slater started the Defenders of the [Historic] Upper East Side?

Ashby: Yes. About ten years ago, yes.

Q: In 2003. And that was prompted by the Citibank development?

Ashby: Well, that was after the Citibank development, but it was after so many little fights that have to start up. We were asked to do it because rather than have to—everybody has to start from scratch—that we were there and it had become part of us. And we’re 501(c)3 [nonprofit] so you can make your contributions—you know, you could start raising money day one and that kind of thing.

Q: Because the people who objected to the Citibank development they formed their own little organization.

Ashby: Yes. They were called Citi Neighbors [Coalition of Carnegie Hill].

Q: And you felt like—?

Ashby: Oh, we were involved with that. Yes.

Q: But you could offer more support for future projects?

Ashby: I mean they wouldn’t have had to start it. I mean, they would have started, but they wouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel every time.

Q: Do Defenders, do they have an office space that they shared with the, with each other?

Ashby: No, we have a secretary who works out of her own home. She keeps the files and stuff like that.

Q: And answers requests.

Ashby: Excuse me?

Q: And fields requests from organizations?

Ashby: Oh, we usually do that. Yeah. Because she doesn’t work for us full-time.

Q: And how often do you find that the Defenders of the Upper East Side disagree with other preservation organizations? Do you try to maybe change the discussion a little bit by taking positions that are a little more strong than other groups might?

Ashby: I think most of the preservation organizations—I don’t think we have all that much in the way of disagreements. I think one thing that we determined that we would do is, we would not be dependent on any generous donors. Because I think once one gets beyond a certain stage and you start having an office, and you start having fixed expenses, then an organization will become timid, because some of their bigger donors want to do something that you don’t want to. Or their friends do or something like that. So we determined that it would not become like that. Our secretary works for us on an hourly basis. There are times when we’re busy and times when we’re not so busy. Things go like that, they don’t happen in a nice, neat way. Every nine months you get a project or something. You probably get four in a week and then nothing for a year. But we didn’t want to be sort of prisoners of our finances.

Q: So do you think the real difference between the Defenders of the Upper East Side and other groups is more your martial tone, not so much your positions?

Ashby: I don’t think—I think that we’re here to have a martial tone when necessary. I don’t think we sit around. And we take positions on a lot of things that have no community involvement at all. I think our purpose, other than advocacy, is to be there to make sure that the battles, when they have to be fought, can be fought more easily, more effectively from the start rather than wasting a lot of time starting yet another organization.

Q: Have you or any of the organizations you’ve worked with been involved with working with the MTA [Metropolitan Transportation Authority] on the construction of the second arm of the subway? I know on the East Side there have been some controversies about it.

Ashby: Not our organization. I think it’s a tragedy for those businesses along there and I think for the people who live there it’s pretty rough. I think you have live another fifty years to see the end of it—

Q: To see any positive results.

Ashby: —and then you only get from 63rd Street.

Q: Are there any new projects in your neighborhood that you’ve found exciting or pleasing from the very beginning or have you always felt like you need to push to get good results—something that’s appropriate for this area?

Ashby: No. Some people have done an excellent job. The Willard [D.] Straight House, that used to be the ICP [International Center of Photography], at 94th [Street] and Fifth [Avenue], beautiful restoration job. The old Vanderbilt house I think it was—no, the Baker House [George F. Baker Houses] on 93rd Street between Madison [Avenue] and Park on the south side. Beautifully restored by Carlton Hobbs who is an antique dealer. Did a beautiful restoration.

Q: I’m curious, what did you think of the expansion of the Jewish Museum?

Ashby: Of the?

Q: Of the Jewish Museum.

Ashby: I thought that was a very good expansion. There are people who feel that it has to be a different modern style to reflect now. I don’t. I feel that that was sensitive to the existing building, a slight differentiation so that you know that it’s different. That awful little modern pavilion that they had there before certainly didn’t add to anybody’s character. I think they did an excellent job on that. I’m trying to think of other things that have been—I can’t think. Well, we all fought against the proposal by the Russian church at 93rd Street and Park on the northwest corner, the old Baker house. They wanted to fill in the garden and do lord knows what else, dig it all up. I think they finally had enough opposition, including from their parishioners, that they dropped that.

Q: Do you find it more difficult to push back against public institutions like churches and schools when they want to do expansions and make changes than against private interests who are trying to do development?

Ashby: Yes. I think institutions all over the city—they all want to expand. The Spence School had a fairly decent addition. It goes west next to the Cooper Hewitt [Smithsonian Design Museum]—now has bought property on the block that has got a connector that is blocking people out, windows obscuring other people. I think that the institutions come in with a sort of holier than the rest of us approach, and how can you stop us from curing the sick, and teaching the young, and getting down on our knees and praying. But then they all compete with each other, they all advertise. I figure if you’re all that wonderful and all that needed you don’t have to advertise.

Q: And are there any projects like that for these institutions—are there any lessons?

Ashby: Yes. There is a project from Memorial Sloan-Kettering [Cancer Care]. I forget which street it’s on. It’s on 67th [Street], something like that [phone ringing].

Q: And how often do you find yourself I guess answering people’s questions or being involved?

Ashby: You mean in the community?

Q: In the community. In the last couple of years I’ve seen you quoted a lot of places about signs on the Duane Reade, and subway stops and, I don’t know, Lexington Avenue and all different issues having to do with the quality of life or the character of the neighborhood.

Ashby: Well, I guess because I’ve worked at it for so long.

Q: Everybody just knows to turn to you for a—

Ashby: Excuse me?

Q: Everybody just knows to turn to you for a comment?

Ashby: Well, a lot of people think I can. I hope I can answer [laughs]. I try.

Q: Aside from the Landmarks Committee on the Community Board, are you still very involved with other organizations even though you’re not—?

Ashby: No. Just with Defenders. I’m dormant now, because DOT [Department of Transit] is so unhelpful about it, an organization that I started to put in historic streetlights. And we’ve done it on 91st, 92nd, 93rd, 94th Streets. We’ve done it down in the 70s [Streets] in Treadwell Farm [Historic District]. But the DOT used to be more cooperative and install them, but now they won’t install them. We always donated them. We just raised them on the block and donated them to the city, but now they insist that we install them too. And A, it makes it much more expensive and B, we’d be stuck in the middle if the light didn’t work. So until we get a friendlier Department of Transportation, we’ve kind of had to hold off on that. But I liked doing that because I think it makes such a difference. People on this street want it and in a more reasonable environment I will certainly go back to doing that.

Q: Are these similar in style to the, I guess the bishop’s crook?

Ashby: Yes. Well, it—

Q: Are they a little bit different for each neighborhood?

Ashby: Well they go mostly on the side streets. They go on Park and they go on Madison—the narrower avenues. They traditionally go on all cross-town streets, but DOT wants you to put in what’s called [Type] M poles, which are not bishop’s crook. They’re decorative, but they’re not the same. Park Avenue—Fifth Avenue, there’s the Fifth Avenue pole [phonetic], which they want, which is also used on Central Park West.

Q: And were there issues in other neighborhoods that you’ve been involved with? I know that you commented on the changes to the Durell Stone building [2 Columbus Circle].

Ashby: The what?

Q: The Durell Stone building on Columbus Circle. You commented on that as well.

Ashby: Oh, yes, that was a while ago. Yeah.

Q: Yeah, where they changed it. Are there other issues in other neighborhoods that you’ve been involved in?

Ashby: We helped the local—I mean, I sort of gave a little bit of voice to the local organizations and then a synagogue on Central Park West wanted to put a great big building up in the mid-block, and we certainly spoke for them. And we were part of the lawsuit down over at St. Vincent’s [Catholic Medical Center] proposal to take down—a good building and put a huge tower on it. But then that—

Q: The one on 13th Street.

Ashby: They went bankrupt so that was the end of that. But yes, we were one of the plaintiffs in that suit.

Q: And how often do you work with organizations like CIVITAS that mostly work in neighborhoods north of here on the east side?

Ashby: I was one of the founding board members of CIVITAS, but I haven’t been involved for years.

Q: So then you’re mostly focused on this immediate area—

Ashby: The Upper East Side, yes.

Q: —and south of here?

Ashby: Yeah. That’s our focus, but we would hope for—you know, when we have a problem, we want support from other people. We’re trying to get the rest of Park Avenue designated at the moment. It’s ridiculous that it isn’t all in a historic district. We’ve got it on the National Register [of Historic Places], but the city hasn’t designated it yet. We lost two of the earlier buildings and we have—the earliest buildings are now under threat between 89th [Street] and 90th [Street] on the west side. Those are pre-civil war buildings, little buildings. I mean Park Avenue’s early history is not at all elegant. It was just Fourth Avenue and it had locomotives going up and down the middle and it certainly wasn’t a place to live. But I think to lose its early history is a tragedy. There’s so little of it remaining.

Q: Yeah. It’s been redeveloped so many times.

Ashby: Yeah. Well, once it got—instead of being cinders and soot, once it got covered over and had gardens, then it became the elegant avenue that’s world famous. I mean other avenues are beautiful. Central Park West facing the park is a beautiful avenue and it’s mostly protected, but nobody in France would have ever heard of Central Park West but they would have heard of Park Avenue. And they’ve heard of Fifth Avenue, but only as Saks Fifth Avenue. They haven’t heard of Fifth Avenue as a residential avenue, which it’s famous for. But Park Avenue is world famous for being an elegant residential avenue. And if we can’t keep the early history there, if we can’t keep irresponsible co-op boards from changing the windows, it’s a sad comment on this city.

Q: And there was some discussion about expanding the Carnegie Hill district towards the water into what I guess was called the Hellgate Hill area.

Ashby: Oh, yeah. Well, Hellgate Hill is only between Lex [Lexington Ave] and Third [Avenue]. It’s not over toward the river. And that’s very controversial. I don’t know why. It’s led by a man who did something terrible to his own house, so I guess he wanted all his neighbors to have the right to do it. I think people get frightened of landmark regulations when they really shouldn’t. I had somebody tell me that she was opposed to a historic district because she wanted to get a washing machine. Well, it’s not going to keep you from getting a washing machine. It’s not so historic that you have to go down to the river to do your washing.

Q: How much time in your career have you spent dispelling myths about what’s required by landmark designation?

Ashby: Oh, a tremendous amount of time.

Q: And what have you found is most effective when you’re talking to people to assure them that this is a very—[crosstalk]?

Ashby: There is no sense in saying that it will not provide another layer, but I think it protects property owners from the depredations of their neighbors and in the end, they’re going to end up with a better house. We turned down a man who had a proposal on 92nd Street who had a wooden house. A little about 1860 wooden house. And he had a proposal, among other things, to put in vinyl siding and he got turned down. I talked to him later when somebody in the neighborhood had built the Y [YM-YWHA], the 92nd Street Y had a bad proposal—and when he called me about that, he thanked me for turning him down. He said it was his architect’s idea that it would be much more easy to maintain but that it was absolutely right to have a pre-war, pre-everything built. An almost mid-Nineteenth Century wooden building would not have any vinyl siding.

So I think people learned to appreciate what they have and I think the regulations stop—if people are of the mindset that nobody should ever tell me about what I should do about anything in my life, and I made all this money so I’m going to spend it the way I want to, those you don’t persuade. But I think people as they go along and see the difference that the right windows make and see how much harm stripping ornament does to the look of a building. And some ornament of course is protective. That it is lipped keeps rain off the surface of your building and if you take it away your stonework is more vulnerable.

Q: And going forward, what do you think is the most pressing issue for the preservation of this neighborhood or other neighborhoods?

Ashby: Sorry, what?

Q: What do you think is the most pressing issue for the preservation of neighborhoods in New York City?

Ashby: In the whole city?

Q: Or specifically in this neighborhood what do you think? Is it development or is it the slow changes to the character—?

Ashby: I think the threat of losing historic features, historic character, historic fabric—I think that’s a big threat. In this area, and I’m talking about the Upper East Side, I think we’ve got a much better zoning than we had. During the time I was president of Carnegie Hill Neighbors we got the whole area rezoned in one way or another. The side streets became R8B, the height limit came down on Madison Avenue. You lost the bonuses on Park and Fifth, and the wide cross-town streets. I think some of these things grow out of buildings. There is a building that I think is 85th [Street] and Madison that is in the Special Madison Avenue Preservation District, which is a zoning district. When it went up, we thought it was impossible because of the zoning that was in effect then and zoning lot mergers they actually could get a building that was much taller than they ever wanted. And so that was when I was still at Carnegie Hill Neighbors. It was not Carnegie Hill, but I think we would be under the same threat. We proposed a zoning change that limits the height and it could not be built now. The Citibank site could not have been—it wasn’t built and could not have been built to the height that it could have been built prior to that zoning change, which came in I think about—it also came about 1993.

Q: And how often did you find yourself fighting against zoning variances? You succeeded in getting the entire area zoned more appropriately, but how often do you find developers trying to get variances from the city to exceed the zoning that you helped inspire?

Ashby: They do happen. I think the original—I mean, there are a lot of Whitney [Museum of American Art] plans but the Whitney plan by Renzo Piano that needed—the whole thing was variances. I think we were simply lucky because they went downtown. But I think that it’s an institution and they got variances that they were not entitled to. I think that the—I don’t know if you’re familiar with it, but the Cornell decision [Cornell University v. Bagnardi] which seems to be what all these institutions run under that they don’t have to meet the findings really, because if they need it for their programmatic needs—is what they’re talking about—they got a variance for that. But now it’s been bought by a developer and he’s having a bad time down at the Commission that acquiesced to Piano’s plan is just far worse than anything the developer had in mind.

Q: For the two or three brownstones that are just south of the museum?

Ashby: Excuse me?

Q: A developer purchased the two—?

Ashby: He bought all six brownstones and the two townhouses on 74th Street.

Q: In the expectation that he would be able to develop them?

Ashby: To add to the top. Of course he’ll need—whatever he does he’ll need a variance because you have a street wall requirement and he’d have to set it back and he can’t set back at the height of those brownstones. Whatever he does there he’ll need a variance. But Piano needed nothing but variances. I did a drawing—I took a copy of his drawing and I colored in red everything that was a variance and the whole building was in red. We couldn’t see anything that wasn’t.

Q: And how many organizations worked together to object to Piano’s plan for the Whitney?

Ashby: Well, we worked—the local group that founded it, I think they called themselves [Coalition of Concerned] Whitney Neighbors, we worked in partnership with them, and then other organizations came out and protested too.

Q: So Carnegie Hill Neighbors and Friends of the Upper East Side [Historic Districts] and [crosstalk].

Ashby: I think they all did, yeah. I can’t remember who was in and who was out. And I think one thing that institutions and developers have learned is to get a well-known, internationally famous architect and then people are so afraid of looking like the people who dismissed Van Gogh that they’ll accept anything with a big name on it. I mean this was a tower, a windowless tower, clad in steel plates. Now nobody is going to tell me that they can honestly say that’s the appropriate for the Upper East Side Historic District or for Madison Avenue. But people were just afraid to say the emperor has no clothes here.

Q: It doesn’t really sound very appropriate from Marcel Breuer’s original building either [laughs]. Well, I think we’ve gone through all my pre-prepared questions. So I’m not sure—I apologize, I’ve never interviewed anyone.

Ashby: Excuse me?

Q: I apologize. I’ve never interviewed anybody before. I’m not sure how to wrap all of this up [laughs]. But thank you for answering all of my questions.

Ashby: Oh. If you have any more, just give me a call.

Q: I can certainly give you a call. Do you have an e-mail address? I can also e-mail you.

Ashby: Yeah. I’ll wait until you’ve got something to write on.

[END OF INTERVIEW]