Herbert Broderick

Herbert Broderick encountered the unique challenges of preserving religious buildings while fighting to save the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew.

Art historian and Upper West Side resident Herbert Broderick is a veteran of the 1980s battle to preserve the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew on West End Avenue. When the church sought to replace its eclectic 1890s building with a residential tower, Herbert Broderick and his wife, architectural historian Mosette Broderick, helped organize their neighbors to save the structure by agitating for landmark designation, which was granted in 1987. In this 2010 interview conducted by Pratt graduate student Zack Lemie, Broderick provides his perspective on the events surrounding the fight over St. Paul and St. Andrew and the challenges involved in securing the preservation of historic religious structures.

Herbert Broderick, Session 1

Q: Um…all right I suppose we could start by: can you tell me a little about yourself, where you’re from, what brought you to the Upper West Side?

Broderick: Well let’s see: I was born in Maryland and I grew up on Long Island [Q: like myself], I went to Columbia College, and that sort of started my career as a Manhattanite, Managed to get back to graduate school – finally completing a Ph.D. – after Vietnam, although I wasn’t there. I was teaching art in upper New York State instead. So my wife and I met at Columbia as graduate students in Art History. We were fortunate enough to get an apartment in the early ‘70s on the Upper West Side and we’re still there [Q: So you just kind of…] and we just kind of kept on going.

Q: What got you into teaching?

Broderick: Well, I was always interested in art. My grandfather was an architect (with Sloan & Robertson in New York in the 1920s) and a sculptor. I took an Art History class in high school, which is an unusual thing to be offered in a public school. That was sort of the hook. I am presently an Associate Professor of Art History at Lehman College/CUNY where I have taught for the past 32 years. My specialty is medieval manuscripts and iconography. Recently I was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, affectionately known as “The Ants.”

Q: What part of Long Island are you from?

Broderick: Well, I grew up in Huntington and Halesite, which is where Nathan Hale (a school teacher & patriot) was supposed to have been captured by the British.

Q: I’m familiar, I’m from Westbury.

Broderick: Oh yeah, well, it’s on the route.

Q: North Shore.

Broderick: Yeah, terrific.

Q: When you got to the Upper West Side, what was the atmosphere like?

Broderick: Well, that was before it became the gilded ghetto of sorts. It was a little rough. We’re on West End and West 86th Street and we moved there in 1971. They called it an “emerging neighborhood” at that point. Right now it’s at the top of the heap.

Q: What were your neighbors, I guess, the business district, and your neighbors – was it a community at that point?

Broderick: You know, it was this multifaceted thing that the Upper West Side still is: academics, therapists [Q: So a nice crust.], editors, you know that kind of emphasis on the brain groups. But there were these really interesting things that just don’t exist any more. The thing that stands out in my mind there was this Daitch Dairy shop on Broadway between 85th and 86th that the clerks still added up the figures on a brown paper bag with a pencil. [Q: One of those.] And a great two-foot square slab of butter, so if you wanted a pound they cut it off and wrapped it in paper. So it sounds like we’re talking about 1886.

Q: So, it was still hold over from the previous…

Broderick: No, it was in transition.

Q: How would you compare it to other neighborhoods, let’s say downtown?

Broderick: Well, it was really a residential neighborhood and it had convenient things: grocery stores…

Q: Stable…I mean…

Broderick: Very stable, it sort of was a kind of families area, even in the wild ‘70s.

Q: Was it crowded?

Broderick: No, not really, it was a very pleasant place to be, still is. [Q: I’m sure it still is.] Riverside Park, not far away, so it had many attractions.

Q: I know you live across from the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew.

Broderick: Yes, that’s always been kind of an issue, but I guess one might say if you can’t rise to the defense of something that’s right in front of you, well, what else can you do?

Q: Well, what were your initial thoughts, I’m sure you noticed it right when you moved in?

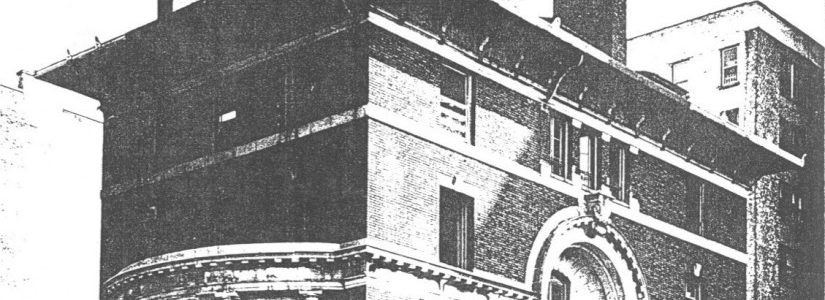

Broderick: Yes, my wife and I, in the Art History racket, sort of had an eye for things like that. [Q: Certainly unusual.] You look out the window even today you think you’re in Italy or somewhere in Europe. In fact, parts of the building are modeled on Sant’Andrea, Mantua.

Q: So you were, I’m sure, happy when it was designated a landmark?

Broderick: Oh definitely, you know, we really worked at making it happen.

Q: Had it been threatened before?

Broderick: Well, to be frank, we weren’t entirely aware of the circumstances over there. Not being Methodists we never availed ourselves of the place. But I guess for a lot of people in our neighborhood, the wake up call was the loss of the Church of All Angels on West End and West 81st street.

Q: So it was a time when…

Broderick: Suddenly this church was torn down and people were just really shocked. It’s still tragic to think that you go to the Metropolitan Museum, the American wing, to see the pulpit by Carl Bitter that was in that church and the church itself is gone [Q: That’s unfortunate], replaced by some undistinguished looking high rise building.

Q: What was the feeling toward preservation in the neighborhood? Was it something that was flourishing?

Broderick: Well, I wouldn’t say flourishing. You had a group of people who were predisposed to ideas history about art. Not a totally rare commodity. And there were a couple of things then that sort of happened shortly thereafter: the battle for the Rice Mansion on Riverside Drive, that kind of galvanized people. There were these sorts of wake up calls happening.

Q: Is that what got you involved with landmarking?

Broderick: Well, we were sort of aware of these issues and the Rice Mansion. I guess I should say my wife kind of got pulled me in there first because she’s technically the architectural historian.

Q: I’m not familiar with the Rice Mansion.

Broderick: Rice Mansion, yeah, it was a private house, belonged to Isaac Rice on Riverside Drive and, I guess it’s about West 89th or so, right on Riverside. I think the distinction was the only freestanding private house still left there on Riverside. It had been bought, I think, in the 1950s by a yeshiva so it was called Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim – it’s now called the Yeshiva Ketana School. And the yeshiva wanted to tear it down and build an apartment building and have a school at the bottom and raise some money, the usual kind of story.

Q: But it survived?

Broderick: Yeah, after a very long and very unhappy battle, it’s a designated landmark.

Q: So it’s still the only freestanding… [Broderick: I think so yeah.] It’s owned by a Columbia Profess…

Broderick: Well, no it’s still the Yeshiva.

Q: So I am thinking of something else.

Broderick: It was a very unhappy experience because there was a lot of bitterness and unpleasant conflict [Q: I’m sure.] which unfortunately has characterized this whole angle of religious architecture and preservation

Q: As a preservation student that’s one thing that we a…

Broderick: It’s a hot potato [Q: Exactly.], it doesn’t get any better.

Q: So what got you specifically, your involvement in Landmark West?

Broderick: Well, Landmark West didn’t really exist yet. The thing is that it was these kinds of events that sort of gave people the idea that something had to happen here; they needed some kind of organization. Because you see then Central Park West; things were happening and I think Landmark West really emerged first out of, well the efforts of Arlene Simon, and a number of people on Central Park West dealing with the Fourth Universalist Church over there, and the

Church of Christ Scientist [Q: A lot of church related…], and Shearith Israel so there were a lot of really tricky things happening over there so that sort of got started and then people over on the West End Riverside angle sort of got together with it.

Q: So what, when you saw what was happening with the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew they wanted to obviously building a tower there, what were your thoughts on what was happening on the other end?

Broderick: Well, it was just shocking to think that this was happening, so there were about 3 or 4 of us who got together in April of 1980. This is really ancient history.

Q: This was before it was landmarked, right?

Broderick: Oh yeah, in other words: it was this group, the Citizens Committee to Preserve the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew, that worked toward the designation and it took quite a long time.

Q: Who, who else was on the committee?

Broderick: Some of these people have now passed away. The primary people were myself, and Seymour Smallberg who lived in a building next to the church, a woman named Alice Pucknat, and Ruth Smallberg, Seymour’s wife.

Q: I have an article you, a letter actually. One of the things I could ask you now. I noticed it seemed like – I can show it to you. Was there, your tone in the article, or in your letter to the editor, it seemed like perhaps the church had been engaging in a misinformation campaign?

Broderick: Well, if we can be frank, from the beginning this group of people – these three people – we met with the pastor of the church. We asked if we could meet with him. So we went over there to the church parlor and we were immediately introduced to their lawyer, Mr. Klein, from Strook, Strook, and Lavan. And we are kind of going: whoa, we just thought we were going to talk to the minister and see what’s happening, could we help?

Q: So they took a combative position from the get go?

Broderick: Yeah, they said: you know, you people have no business butting in here and get lost, basically. So it started off on a very acrimonious kind of left foot and kept going that way.

Q: Do you think this was because of the other issues relating to churches in the neighborhood they kind of figured that they were…

Broderick: They realized that this was going to be some kind of a battle. The thing that we came to find out not too long thereafter was that the president of the congregation, a Mr. Morris Gurley, I’m not even sure if he’s still alive, but anyway, president of the congregation of the church, but also happened to be Sunny Von Bulow’s trust officer. And so Sunny Von Bulow, I don’t know if you remember her but [Q: I’m familiar with the name.] she was in a coma for some time due to her husband allegedly injecting her with an overdose of insulin – Alan Dershowitz got him liberated (Reversal of Fortune – the movie) – but she’s no longer with us. Anyway, so there was access to some kind of money to pursue this on a legal basis, because they ultimately after this dragged out process of having it landmarked and then challenging it, took it to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Q: And that whole issue was that they had a dwindling congregation and…

Broderick: Well, it’s a church that seats I think twelve to thirteen hundred people and on a good Sunday they might have 75 people there. So the original things that we wanted to discuss with them was multiple use, getting together with other congregations, do something, which to jump a head here, historically, is actually what happened. [Q: I was going to say that’s how they survived.] That’s how it’s still standing in a sense, because they forged a relationship with B’nai Jeshurun and if I’m not mistaken, the synagogue pays them now rent, to use the church. And so for everybody, it’s a win-win situation.

Q: It’s kind of ironic too because that’s what happened in the 30s with the Church of St. Andrew, which merged withthe Church of St. Paul…

Broderick: The Methodist Episcopal Church of St. Andrew, whose building is now actually a synagogue called The West Side Institutional Synagogue. And so the St. Andrew’s congregation merged with St. Paul, St. Paul and St. Andrew. And now the church is used by B’nai Jeshurun, and over the years it’s been used by different congregations as well and unfortunately West-Park Presbyterian Church which is the hot potato of the moment.

Q: Which was just landmarked right?

Broderick: Just landmarked, but still in trouble.

Q: I think they want to put it up for sale now right?

Broderick: There’s a big sign now outside, “Church for Sale”. So anyway, that congregation has moved in with St. Paul and St. Andrew, which is nice in a way but [Q: They’re finding a way, at least.] it’s an ongoing issue. I mean this thing goes back to 1980 and we are still talking about the same problem.

Q: Well if they had, besides for the fact they wanted to build a tower, if they had successfully demolished the church what do you think the impact would have been on the community?

Broderick: Well it would have been devastating. The tragic thing is, is that this set of churches on the Upper West Side from the 1880s and 90s forward, were on these choice corner plots [Q: Certainly a prime location.] and its prime time stuff, real estate wise. So they’re looking at huge potential, before the recession, looking at huge potential for completely, in a sense, unrestricted zoning on the avenue, you name it how high.

Q: I know you mentioned it a few times I think it was something the extent they don’t have a constitutional guarantee to maximum profit and they’re a tax free institution…

Broderick: Well, that’s again this whole knotty issue about not-for-profit, and particularly religious institutions, separation of church and state. Churches and synagogues and other religious bodies may kind of think that they are kind of like the Vatican, a sovereign state, the Vatican City is a separate country, and it’s a sovereign nation. But that is not really how it works. In this country, churches are part of the civil fabric and tax exemption is a way of supporting them in a sense, that they don’t pay taxes.

Q: And they didn’t have a plan they actually didn’t have a…

Broderick: They would never reveal it. You know this is what protracted the whole process. They kept saying they are considering options, they need to look at various things, they have various things, but nothing ever really emerged.

Q: Do you think that was baloney or…

Broderick: It’s hard to say because I think developers, even now, are wary of what to do because if this thing is pending in some sense to be designated could spoil the whole business. At one point there after, well while the designation was pending, Kent Barwick, sent around an architect to kind of look into the issue. While the designation was pending between the hearing in May of 1980 and the actual designation, November 81, Kent Barwick was then chairman of the LPC, recommended to the church the services of an architect, Joseph Wasserman, of the firm Rosan, Sampton, and Steinglass, who prepared a preliminary study, sketch, proposal for a 25 story apartment tower incorporating significant portions of the present historic church building. And at the time we kind of thought that was a little out of order. [ZL. I’m sure.] And there may have been other suggestions brought to them.

Q: Did the church get more angry as this played out over a span of years?

Broderick: They were angry all the time. It started out angry. At the moment under the current pastor their attitude seems to be different. And this partnership with B’nai Jeshurun is kind of, I think, given them some sense of viability in the building. But the previous three ministers, they went through three of them in the process here, were not happy people. At one point we were told, and I’m not sure if this is true, that in the Methodist hierarchy of things, that pastors retirement funds are sort of pegged to the finances of the individual church, their retirement was linked to that particular place. So there are always issues with money.

Q: And that seems like that was the major, I mean they were in a position where they felt they didn’t have, I remember one of them was quoted as saying: “they want us to preserve this museum.”

Broderick: Well, one frankly can see that there are enormous issues, a gigantic building seating twelve hundred people needing to be heated and repaired, but the attitude was never: let’s try to find some solution, it was just: let’s get rid of this white elephant, and garner a lot of money in the process.

Q: Do you think they would have legitimately rebuilt a church at the bottom of the tower, or do you think they would have just gotten out?

Broderick: Well they might have gotten out all together or they might have, what sort of in that black humor expression emerged, “Citi-Corped” it. That was another trend setter: St. Peter’s Lutheran Church selling to Citi Corp for Citi Tower and there is a church in there, it’s quite interesting, but not exactly what people had in mind. So they might have “Citi Corped”it, put in a little church space.

Q: I know you had mentioned they had a large dining facility and they had a community service program.

Broderick: Yes, and they still do. It’s a marvelous thing. I mean, it’s a huge building and the entire lower level basement area is this West Side Campaign Against Hunger. It has this food bank and all kinds of facilities for helping people. It’s funded by City of New York. I don’t know what the relationship exactly is, with the church, but they got some enormous grant, not enormous, but they got a very substantial grant and rehabilitated this whole space. It’s very attractive.

Q: How long ago was that?

Broderick: This may be now the grant maybe five, seven years ago but the thing was functioning before the grant. It’s a terrific space.

Q: Had they been successful with demolition, how do you think the absence of that program would have affected…

Broderick: Well, it’s a major thing on the West Side and for senior citizens, for other constituencies to have this food bank and other services, Meals on Wheels coming out of there.

Q: So it would have been significant…

Broderick: It would have been a huge loss and people said that in various ways the doorman of a high priced building is not going to be holding the door open for people to go into these social services. It just didn’t seem like it would be likely.

Q: So it would have been condos, was it a proposed condo?

Broderick: Probably something like that, and ironically, today diagonally across the street on West End and 86th, the south east or south west corner, is this gigantic new building that is just about to be finished by Extel. They are advertising every Sunday in the New York Times magazine, five bedroom, thirty some million dollar apartments, looking out on the church.

Q: What did that building, did that building replace anything?

Broderick: It replaced unfortunately one rather nice 1880s brownstone, but on the corner a messed up 1950s strip down, no loss, I’m sorry to say.

Q: You mentioned the church had the option to sell their air rights to…

Broderick: Yes they did. Again these things, talking about things 30 years ago I’m not exactly sure how to corroborate this, but it was understood at the time that Ian Bruce Eichner, this developer who developed this building on Broadway and 86th St., called the Boulevard, had made offers to buy the air rights, and they would have been worth, at that time, five, six million dollars, but the church didn’t want to play ball with that.

Q: Do you have any idea why the church…

Broderick: My hunch is that they figured they could get a lot more than that. So why give it up? And be still stuck with keeping this building that they didn’t seem to care about.

Q: Well I’m curious about your thoughts; it seems it’s definitely a sticky issue between a church that doesn’t have the funds to maintain itself juxtaposed with a landmark that needs to be maintained. What do you feel?

Broderick: If I had the answers we wouldn’t be probably sitting here because it’s an eternal issue, at least in Manhattan. The specifics of the Manhattan situation where these things are intrinsically valuable, in other words the problems outside Manhattan preserving churches in Buffalo is a different story because nobody is looking to buy these things for huge prices. But I think the continued survival of St. Paul and St. Andrew is an example that it can be done, but it takes a lot of work where you have to put together these pieces, multiple use, grant funding, it takes work. We were trying to be helpful and to help them, but it just didn’t want to seem like they wanted to be involved with the process.

Q: Which is odd because you would think a church would want to be involved in their local community to an extent…

Broderick: Well you would think so, but they just had this fortress mentality, that just we’re just gonna fight this, and we don’t want to look like we are giving in to the opposition in any way.

Q: Would you have been fine if the church left but the building remained intact? I know you mentioned turning the rectory into apartments.

Broderick: Well, this was one would like to see it stay in the function that it’s meant to be. It’s a delicate issue because people say, these elitist preservationists, they’re worshiping bricks and buildings, and we’re a church, and spirituality, and all this sort of thing. If there were other kinds of multiple uses that could happen would be a good thing. The church is huge when you look at the plans and you actually go in there. This was someone else’s idea: that some of that space could be reconfigured for income producing, like doctors’ offices and things like that, that had some kind of charitable community function of a sort, not a bank branch necessarily. But anyway, no, they didn’t want to think about any of that. Sadly, also the commission, landmarks commission did not designate the rectory, there’s this set connected, quite large chunk of property facing West End Avenue. So that’s still a soft developable chunk of real estate there.

Q: And there’s been no attempt at converting it?

Broderick: Not that we know, they seem to be in a, because we have no real inside connection to what their current thinking is but it’s just there.

Q: Are they still combative…I don’t know, they’ve changed.

Broderick: Well the new minister is a very different person and quite frankly, we really haven’t had any kind of interchange with them, so I’m not quite sure what their mood is. I think it just seems to be working, because of the relationship with the synagogue, and for all practical purposes seems to be carrying on, which is nice. [Q: That’s for sure.] And then of course they have the neighbor there, the Episcopal Church of St. Ignatius, that’s right next to them. So these two religious institutions, but it’s night and day. St. Ignatius has had the good fortune to have had all types of benefactions and they recently cleaned the building. It’s just in totally tip top shape. At one of the many, many meetings on the issue at Community Board 7, someone in the audience asked the minister of St. Paul & St. Andrew’s –“what about the church next door – how’re they doing?” And he replied, “Well, what can I say, they’re like more into worship.”

Q: St. Paul and St. Andrew’s, does it need work?

Broderick: Oh, sure, and they have done work. In fact they are just doing work right now repairing the Spanish tile roof. There are ongoing issues: the cast terracotta pieces of it fall off. They did a kind of stop-gap campaign about a year or so ago sort of trussing it up. They wrapped up parts of it and secured it with wires [Q: So just a stabilization, mothballing it for a later…] Stabilized it, well it showed some positive movement there. This stuff this is not cheap, I’m sure [Q: I’m sure.] to do it.

Q: There was a group other churches and synagogues had stood behind St. Paul and St. Andrews at the time. Did that create an awkward feeling in the neighborhood; you had the local citizens versus all the religious institutions?

Broderick: Yeah it’s not pleasant. Again its sort of spill over from the Yeshiva Chofetz Haim thing, the Rice Mansion. There was kind of an air of acrimony, which was not nice. Again this idea of wrapping this cloak of church privilege around the issue; in some kind of sense that these institutions are like the Vatican, sovereign nations. They just didn’t want to interact…

Q: How big did it get as far as New York City was concerned? Was it just an Upper West Side Issue?

Broderick: Well to be frank that was part of the problem because simultaneously you had the St. Bart’s issue. This was really a wild period there. The St. Bart’s issue, which you know there are various opinions, but I’ll just try to give you a sense of the thing. Well this thing was very important and it’s on the East Side, we just have to focus on this. We felt, at the time, a kind of lack of interest in this building on the West Side.

Q: Was that because the Upper East Side was more established…

Broderick: The Upper East Side is the Upper East Side.

Q: The Upper West Side is…

Broderick: The Upper West Side is the Upper West Side. At the time it was a little more different, in a sense. I could see the strategic thing, that St. Bart’s was very important indeed, so what happened there had to be, people had to put a lot of energy into it. And then there was this kind of stylistic prejudice, people didn’t really care about the style of St. Paul and St. Andrew…

Q: That’s so unusual though, because the style is so unusual.

Broderick: Yeah, but it was seen as: if we have to let some thing go, this thing is kind of a mishmash…

Q: Do you credit that to a lack of understanding of church architecture at the time?

Broderick: Yeah, in part, Yeah in part. Then this kind of wild card got in there: Richard Guy Wilson had done this exhibition, the American Renaissance Show, which was quite groundbreaking to talk about end of the century American stuff, but he threw in this idea of calling the style “Scientific Ecclectism”. And this kind of gave the church a kind of red herring to sling around. You know who has ever heard of this, what is this; they’re just making up stuff. From an academic point of view, I understand what he was trying to say: this old fashioned sense of the meaning of scientific, the word, as “knowledgeable”, from the Latin “scientia”, what the Germans call Wissenschaft – Scientific Eclecticism. But it just sounded like a wacky…

Q: Do you think that played negatively…

Broderick: It did because people didn’t have a clear recognizable name for this building.

Q: I’m curious, did the normal Upper West Sider, was preservation or the saving of their neighborhood, was that something that mattered to them?

Broderick: Well, it mattered a lot to some people, didn’t seem to bother other people. There were people who said: “This is terrible, the church has to have its rights, we don’t care what it looks like if it has its social functions.” Every opinion, it is the West Side, very strong opinions. So in soliciting signatures for petitions and so forth, even people living directly across from it would say: “Yeah, I’ll buy some new draperies – I don’t care.” Or this other attitude: “Oh, it will improve the real estate values.” We got every attitude from these people.

Q: But you found support?

Broderick: Oh there was support, but there was this broad range of really amazing opinions. Improve the real-estate values, get rid of that junky old building and the vagrants sleeping on the steps, and this is an issue that keeps popping up, popped up over there with West Park Presbyterian [unclear]. So it’s an issue that’s got every angle that you want.

Q: Was there anyone, specifically, that played a leading role, against the hardship application?

Broderick: Well this group of ours, Citizens Committee, we just kept hanging in there, and by that time Landmark West had really sort of come together as a major group, so they were with us.

Q: And they got involved in this later battle?

Broderick: Yeah, we had a lot of support for that because in those days you had the designation and then it had to go to the Board of Estimate, challenges all along the way.

Q: The whole thing played out over a decade.

Broderick: Oh, indeed and then it lead to this hardship provision, the landmark law, so there. They went for it but they weren’t successful in making the case, and the church took it to the Supreme Court.

Q: And, correct me if I’m wrong. They were denied because they didn’t have a legitimate plan?

Broderick: They really didn’t say what they were going to do because in my opinion, our opinion, they just wanted carte blanche.

Q: So they really were just looking for maximum potential use profit, anything they could…

Broderick: Well again we felt that the sort of Darth Vader in this was this Morris Gurley, who was a banker, Sunny Von Bulow trust officer. So he was looking for maximum bottom line dollar stuff, and taking the church along with him, and telling them what to do and they were unfortunately listening to him thinking that he knows what’s what. [Q: I don’t know how that worked out.] Yeah it’s very peculiar, the Sunny connection, I guess it’s kind of a factoid but in Bonfire of the Vanities, the Tom Wolfe novel, there’s a whole fandango about a minister, a Rev. Bacon I believe, being told my the Mayor that if he didn’t co-operate that he, the Mayor, would tell the Commission to “Landmark the Sucker.” And we kind of had a feeling that this was a reference to St. P & St. A.

Q: When you, I was going to say when you walk by it, but when you look out your window and you see it today, what does it evoke?

Broderick: Well, to me it’s just a wonderful thing that it’s still there, and people enjoy it. I guess the sad part is people pass by and you often see people pointing up at it. Sometimes I’ll talk to people if I see them on the street and tell them something. Just the assumption that these things are great and they’re here, but people don’t understand what it takes to keep them here. And the sense that you really do create a kind of cultural amnesia if these things vanish, religious connection to these monuments in that sense or looking at them as part of the fabric of the environment, it’s a big loss.

Q: Since then, how much has your neighborhood changed?

Broderick: Well, there was this flurry of building, this Boulevard thing, which wrapped around behind the church, and now this Extel project on the corner (advertized as “21st-century Pre-War Apartments”), other than that it has been fairly stable. So the big changes are the conversions of buildings becoming condominiums, but maintaining the fabric of the building. As you know, there is this effort to get large parts of West End Avenue made into a historic district.

Q: I’m sure you’re enthusiastic.

Broderick: Oh yeah, it’s just a terrific thing because fortunately. Well, as you know, poverty is the great preserver, and the recession has done marvelous things for keeping the lid on, because just before the big crash out there in 2008, a number of brownstones were quite vulnerable, still vulnerable. [Q: That must have been unsettling.] Yeah, it’s scary because we can’t just sit back and take it easy, stuff is constantly happening.

Q: So if there were a challenge you think your neighborhood faces it would be susceptible to development if the market were to turn around.

Broderick: Well when it comes back, we’re gonna be in some battles.

Q: How advanced is the Historic District designation?

Broderick: I don’t really know I haven’t been able to follow the details. Now that Landmark West is this very active and large organization that it is, there sort of more involved in the details of what is happening. We get rallied for the various hot potato causes and glad to help, but I’m not entirely sure of the specifics of how things are developing, but as you know the Landmarks Commission moves very slowly.

Q: How do you look at preservation now, from 1981 when it was designated, to 2009? How do you think the city has evolved?

Broderick: Well, I’d like to say that there is some greater awareness, but there’s still this sort of aura of elitism hanging around this stuff, I don’t know if you’re ever going to get rid of that thing. Just in recent hearings about West-Park Church, somebody speaking to the contrary, somebody got up and said, “Well this is all being carried out by an elitist coven.” You know, this is still a problem in preservation that it’s conceived as a kind of class oriented economic thing, which is not for the common man.

Q: Which is odd, if you think about it, because here you’re saving a church and what would go up in its place would be a huge condo where only people who could afford 30 million dollar penthouses… you know it’s kind of odd.

Broderick: Yeah, the thing is full of irony, but somehow it’s very hard to get over this issue. To get people to realize that the quality of their life is tied up with these specific structures and this is generally a very good thing. But the religious angle just adds a sort of fire storm element that is part of the whole complexities of the American experience.

Q: And it seems like even over those 30 years a lot has changed, but also nothing has changed because we are still dealing with the same.

Broderick: Its like “plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose” – “The more it changes, the more it stays the same”. You know Palinites and Teabaggers are, “hands off churches, sacred site, can’t be told what to do.” So I don’t know if we have progressed. I would like to say so, I think so, but there is just a lot of taking things for granted, well that’s nice.

Q: How many people do you think appreciate, in your neighborhood, the historic edifices that are in their neighborhood?

Broderick: People appreciate it, but then in the nature of things what are they willing to do about it, is another issue. People are busy, people are strapped. So they may appreciate it, but it’s hard to get some kind of action out of that.

Q: If there was one, one major take away for the whole event between the landmarking, I know that’s kind of a broad question, if you could say there was one thing we really learned from going through this whole process with them, and eventually being successful what do you think that might be?

Broderick: It’s something that’s not easy, that is, stick to it, perseverance, hanging in there. Just keeping on keeping on, because it’s just not subject to easy solutions, it’s a test over a long period of time. Continuing the advocacy and trying to elevate people’s consciousness about these things, but it’s not a quick deal, and again the religious angle just brings in all kinds of other things that are, rough.

Q: Do you think that will ever be straightened out?

Broderick: I don’t think so. In some sense it’s you know, and it’s ironic because the American idea: separation of church and state, I think is generally a very good thing. As you probably know, in Europe, parts of the tax levy are for the artistic patrimony. Whether you’re an atheist or a Buddhist or whatever, you are going to help pay to keep the monuments of Germany and France standing.

Q: We have that debate frequently. Who pays for these things…?

Broderick: It’s un-American to think of doing that. And then I have these sort of fantasy ideas. Fantasy number one is what I call a “View Tax”. In other words, if you’re in the 30 million dollar apartment, and you’re looking out on this picturesque thing, this church with its soaring campanile, tile roof, sculpted angels, etc. maybe you should be contributing somehow to it. It’ll never happen. Who knows? Or, this is fantasy land stuff, developer: yeah you can take this church down, but you’re going to have to reassemble it in Queens where there is this big Korean congregation that’s using some former super market as a church. Let’s have a church that looks like a church.

Q: That’d be great, and as far as Long Island is concerned, we deal with that a lot, and the churches they are building now…

Broderick: Well, as you know, as you go on the Long Island Railroad, past the, what was it, a perfume factory, “Fleuroma” Perfume factory or something like that, a beautiful art deco building that is now this giant, grey, Korean Presbyterian church. Why not have a church that looks like a church?

Q: I share that sentiment.

Broderick: But these are, I don’t know, maybe some bold politician could come up with something. Take it down, reassemble it. I mean, they can do it. Buildings are taken down all the time and put back up – look at the Temple of Dendur in the Metropolitan Museum – all the way from Egypt!

Q: Do you feel that your neighborhood or the Upper West Side in general, is turning over… people wise. You have younger …

Broderick: Yeah, it’s younger more professional and they can be more culturally amnesiac. They’ve got all the iPods plugged in, busy looking at Facebook, I don’t know if they even look out the window anymore. Also, there was a big sea change. We came in there in 1971, we’re now, I think, the oldest people in our building, which is a little bizarre, but, things happen. You know you had editors, musicians, psychiatrists, therapists. Now you have people from finance, big bucks people, bonuses. It’s a big sea change there.

Q: So where do you see it in 10 or 20 years?

Broderick: Well, I guess some of these things depend on this so-called recovery. It just looks like it can only go up, because there is only so much real-estate land, Manhattan is still Manhattan…

Q: So you think that bodes, not well for…

Broderick: Well, I hope it could bode well, but it may take some kind of consciousness raising in the extreme. These people with the affluence to maybe help out. We’ll see, Landmark West—I don’t know if they are plotting this thing [unclear].

Q: Well Landmark West does the, they teach the kids in the schools…

Broderick: Yes, they do and they have done a number of walks. My wife and I have done a number of them trying to raise consciousness, but there still tends to be little gaggles of committed people showing up.

Q: What do you think though, if they are teaching the kids? I was never taught when I was little; an appreciation of buildings is something I developed on my own…

Broderick: I would like to think that this would be good and it’s going to change and bring a generation of people with a real understanding of it [unclear].

Q: I know you have documents, I was going to ask if the archive…

Broderick: You’re collecting these things?

Q: Laura would be the one to talk to about that.

Broderick: I sort of combed out what I thought was important and of potential interest. I was shocked at the amount of it. I still have even more, and I don’t know how much that you want to take. I’ll talk to Laura about it.

Q: I suppose the last thing I could ask is there something that I haven’t mentioned that you wanted to have a say on?

Broderick: Well, I don’t know we’ve covered a lot of topics here. Again some of the, the things that may never change about this struggle, because the things that are needed are on such a large scale and also depend on willingness. I think the best thing is that the outcome of St. Paul and St. Andrew’s, at least at the moment, is sort of what we were saying at the beginning: how about trying to get together with other people and make a go of it. And they seem to have done it and, I’m not trumpeting the fact that they’ve done it, but it is, I guess, what you would call: de facto preservation. And it seems to work, the relationship with the synagogue is a marvelous thing, and they pulled it together. Again I’m not familiar with some of the current details but B’nai Jeshurun, the synagogue, I do know that the reason that they came there was that the ceiling of the synagogue building on 89th Street had fallen. There is this absolutely beautiful building, the synagogue of B’nai Jeshurun, on the side of the street there, and just about 10 minutes before a service was to begin this elaborate plaster ceiling fell. [Q: Full of people?] No, there were no people, no one was hurt. It was, I guess, divine providence, but the ceiling fell. It would have been disastrous. So that’s how they started, they needed to find some worship space, so they brokered this relationship with the church and now they’ve stuck with it. They’ve restored the synagogue and it’s used as well. So there is this terrific, multiple use, in various places.

Q: Do they hold cultural events or theatre…

Broderick: Yeah they have, again the building is phenomenal, the main sanctuary, but it has also this small theatre. I don’t know what the Methodists were thinking there in 1890, Sunday School Theatre. Anyway there’s a resident repertory company. Again all these things are sort of happening, but nobody is really talking about it or celebrating it, or saying: “wow” and

“look how wonderful this is” [unclear].

Q: But you think the church could be used as, kind of, a case study of how you can make it work?

Broderick: Oh sure, it’s just that nobody really wants to talk about it. It works and it works beautifully, and we’re glad that the end result is, that it’s there.

Q: I’m surprised that the Upper West Side Presbyterian Church doesn’t want to…

Broderick: Well, they have joined with them, but sadly the idea is joining with them in order to tear down their own building. Outside St. Paul and St. Andrew they have these banners showing congregation of St. Paul and St. Andrew, congregation of B’nai Jeshurun, and congregation of West Park Presbyterian. There is multiple use there, but at the expense of losing the other building. Again it’s this big issue of multiple use in these very special spaces. To talk about it clinically: a church, the way it evolved, used in the American scene for one hour on Sunday with 1,200 seats. You have this gigantic space that is of course, you know it would be good for theatre; it would be good for music. There was some effort to try to get Bard College, which had this idea of a music program utilizing the West-Park sanctuary, but that fell through for some reason that I’m not aware of. Nobody has come up with a magic solution for worship spaces. There are examples and again, Manhattan is a cultural capital, that kind of multiple use. Get the Philharmonic up there and do community concerts, or something.

Q: You think the neighborhood would be receptive?

Broderick: The neighborhood is already, they’re the clientele that go down to Lincoln center to do the stuff. It’s just you need the impresario; you need somebody to pull it together, somebody to do it. The church is a religious institution – well you know our main function is being a religious institution. We’re not Broadway producers.

Q: You think really it’s maybe the religious institution itself that needs to come to this conclusion: we need to broaden our scope?

Broderick: Yes, and that’s hard because in a sense you are kind of telling somebody what they’re supposed to be. So, we are trying to be as supportive as we can when these things happen on their own. Again, the example of St. Paul and St. Andrew, in spite of itself, is a wonderful example. They probably could just be doing more, in terms or multiple congregations, finding people that need a worship space. At one point they had an Ethiopian church in there, I don’t know where they went, but I heard fabulous music coming out of there. We’re hopeful and I think, again, in spite of itself, a fantastic example.

Q: Ultimately you’re happy, with the outcome?

Broderick: Well, it seems to be fine. It was painful. It probably may get painful again, because the issues just aren’t resolved, there are just so many, hardly resolved factors in this, preservation of religious architecture business. Again, the peculiarities of the American situation, tax exemption, tax exemption means a lot but it’s not enough to do anything, you can’t repair your roof with it. Maybe, I don’t really know the details, whether a church gets any kind of benefit. Do you know that at all?

Q: I don’t.

Broderick: For making repairs. Whether the tax code somehow, but they’re not taxed so…

Q: There is a historic rehabilitation credit, but I don’t know if it would apply to…

Broderick: It doesn’t work with them because they’re not paying any, but maybe some other reward system. Again, that’s tricky. Of course, with Bush and the faith based whatever, it didn’t seem to work out in the preservation zone [Q: Yes.]. Government grants to…well you see the thing is that this West Side Campaign Against Hunger, which is a city sponsored effort, they did pay for the renovation of that space to be used for that purpose so there’s a limited aspect of how the government can support the building [unclear]. So it’s this multi leveled example of all kinds of wonderful things. [Q: Yeah, it’s got everything.] Food kitchen, shelter, multi-use, maybe somebody has to get the word out. These things happen this way.

Q: Maybe this will help.

Broderick: Great.

[END INTERVIEW]