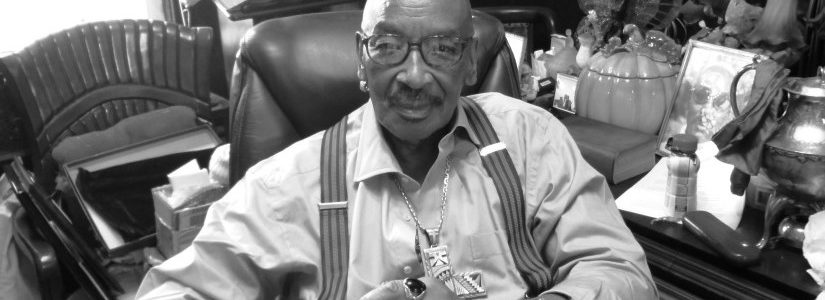

Mandingo Osceola Tshaka

Lifelong resident of Bayside, Queens, Mandingo Tshaka describes his experiences growing up in the neighborhood and his efforts to have Martin’s Field reclaimed as the Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground.

The Old Towne of Flushing Burial Ground, where 500 to 1000 Native Americans and African Americans are buried, was once treated as a park with no headstones or memorials for th0se buried there. Mandingo Tshaka has been instrumental in restoring the park, Martin’s Field, to a burial ground with all due reverence for the interred. He describes his efforts to preserve the site, gaining the support of local politicians, and pushing for visible memorials to the people buried there. He also shares his views on the overall treatment of African American historical sites in New York City. Additionally, as a lifelong resident of Bayside, Queens, Tshaka is able to describe the physical and demographic changes of the neighborhood since the 1930s.

Mandingo Osceola Tshaka, Session 1

Q: It’s Thursday, July 23, 2015. I am here in the home of Mandingo Tshaka to speak with him about his life.

Tshaka: Mandingo Osceola Tshaka.

Q: I apologize for that. Mandingo Osceola Tshaka—to talk with him about his life and his historic preservation work. Thank you for being here and letting me come into your home and talk with you. So I wanted to start by asking you about where and when you were born and what your childhood was like.

Tshaka: I was born in this house on the other side. It was a bungalow at the time. My grandmother, Lillian Selby—her picture is there—she got married in Flushing at Ebenezer Baptist Church. She came from Suffolk, Virginia, and she married George Selby. Three years later, she bought the property. About six years later or so, 1920, 21, she built the bungalow, this house here, this building. Three bedrooms as you look to the house to the left, kitchen, bathroom, living room, dining room, sun porch. 1935 during the Great Depression—she was an extraordinary woman, particularly for an African American woman at that time—she built upstairs: four bedrooms, kitchen and a bath. They called her Mom Selby and in 1935, she opened up a restaurant upstairs, this room here, and it was called Mom Selby’s Tea Room. And the African American women at that time were doing domestic work, they were off like on Thursday and I think every other Sunday, or something like that, so they would come and congregate here. She had a jukebox, a piccolo. And I was up there doing the boogying and the [laughs] jitterbug and whatnot. It expanded and she brought it down here to these three rooms, the dining room, living room and the sun porch. And, what else can I say? December 7th coming in this room, the radio was playing and it was Roosevelt speaking, “A day of infamy.”

I started school in Flushing. And the reason I wasn’t here my grandmother was building upstairs and I think she felt that it wouldn’t be safe for me to be in the house at that time. So I was boarding in Flushing with Mrs. Mary Hicks and her family, who lived on 37th Avenue and Prince Street, Flushing. A lovely family. And I started school in Flushing on 37th Avenue and Union Street. The 109th Precinct is there now. They had one session of me and closed the school down. [Laughing] It’s true. I failed and, yes, I failed all the way through school.

Q: Tell me, what year were you born?

Tshaka: May 12, 1931.

Q: So were you growing up with your grandmother?

Tshaka: Hmm?

Q: So you were growing up with your grandmother?

Tshaka: Yeah. I’ll tell you that story. Are you recording?

Q: I am recording but we can wait for the beautiful clock.

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: Here’s some pictures here you maybe want to—maybe you want to go get them.

Q: Okay. Let me—

Tshaka: This picture was taken down on Main Street, Flushing. I must have been about five.

Q: What a beautiful little boy. Are you wearing shorts and little socks there and a coat?

Tshaka: High top shoes.

Q: And a hat.

Tshaka: Here’s another picture of myself.

Q: Who are you with here?

Tshaka: That’s my grandmother.

Q: This is Mom Selby?

Tshaka: Mm-hmm.

Q: And here you’re maybe three.

Tshaka: Yes.

Q: In your car and your shorts and your socks.

Tshaka: That’s taken the same place.

Q: Lovely.

Tshaka: And this is my mother.

Q: What was her name?

Tshaka: Emily. And this is her sister, Anna.

Q: And they were from Suffolk, Virginia?

Tshaka: No, they were born in Bayside.

Q: Oh, no, they were here, of course. Do you know when your mom was born?

Tshaka: No, I don’t. She was born in Bayside, I guess born here.

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: Here I’m coming into a teenager.

Q: In a suit and tie.

Tshaka: Mm-hmm. And here I am again.

Q: A young man in a suit and tie. So this would have been sometime in the late ‘40s probably.

Tshaka: Yeah. And you know who that is.

Q: There’s President [William] Clinton. Oh, and it’s addressed to you specifically.

Tshaka: Yeah. [Laughs] Is that extraordinary? Never met the man.

Q: [Laughing]

Tshaka: It’s just so extraordinary, I think, my life’s journey. I don’t know what this is. That’s my grandmother, Lillian Selby. You can see in that expression in her mouth, see, she was tough. And those eyes.

Q: Yep. She wasn’t a pushover, huh?

Tshaka: No, no, no, no, no.

Q: [Laughs] Did you have a good relationship with her?

Tshaka: Yes, yes, yes.

Q: Nice. I will put these back when we’re finished. Is that okay?

Tshaka: Okay.

Q: I’ll leave them here. So can you tell me what this neighborhood was like when you were growing up?

Tshaka: Well, it’s never been an all African American community. In fact, it was—

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: It was called Pollock Alley. There was no Clearview Expressway and within this block, that blue house down there, Decosky [phonetic]. Two doors away from me, the third door, or not the houses, the older houses, the name was Helochik [phonetic]. Excuse me. No, it was Feska [phonetic] and next to it was Helochik. There weren’t any houses across the street until you get to the brick house going towards Oceania Street, and once you past that, that was my aunt’s property. And her house sat back and the lawn and all was in the front. On the property on the other side on 46th Avenue and Oceania, there was nothing there, just wooded area. It was country.

Q: And this is in the 30s.

Tshaka: Yes, 20s, 30s, just the turn of the century. From my home to the blue house, there wasn’t any houses. We didn’t have any sidewalks and curbs. If you look in my driveway, you will see big stones. Well, I used to be a bodybuilder, too. And I went across the street and I brought those big rocks and I put them out where the asphalt ended so the cars couldn’t pull right up in here, and I still have the stones or rocks. It was—there was Polish, Russian, African Americans. Me, I’m mixed. My grandmother, she was light, so she came from Suffolk, Virginia, so somewhere there was Caucasian blood there. Though the features, no doubt about the features. Here, this is my grandmother, my father’s mother, Grace. [Shows photo]

Q: I see, lovely.

Tshaka: Her father was a Dutchman. His name was Skank and grandma was chocolate brown, I guess about the color of that statue there, my great grandmother. And her name was Emma Skank. She lived on the next block. Her son, Henry, lived to the—as you approach my home, to the right of me and you go back 100 feet and there was his property. My grandmother had—I think it was two girls. There was Emily, my mother, and Anna. And, um—what else can I think to say? There was still farming here, particularly up on Oceania here and 47th Avenue. They were farming in front of P.S. 31 School up on the hill between—at Bell Avenue. I don’t know why they call it a boulevard because there is nothing boulevard about it. Bell Boulevard they call it. The Weddingfellows [phonetic] had a farm, and it was horses pulling, plowing and the property extended from 46th Avenue south to Rocky Hill Road, today 48th Avenue, down to Springfield Boulevard.

And I was registered in the old P.S. 31 School. You can look up the street there and you can see it. It was a frame building, a wood frame building. And I registered there in 1938. They broke the ground for the current building in 1939. About three years later, we marched into the current building. It was the state-of-the-art at that time. They had fluorescent lights. Never saw anything like that, because we were Depression children. The intercom, never heard anything like that. The beautiful auditorium. It’s still well maintained. The gymnasium. There was a Kindergarten room and all those things were there. And when—

I could always sing. Mind you, I will tell you, I was always failing. But it was family life when I look back at it, family life. And I could draw—the teacher would allow to draw on the blackboard and such and forth. And when we would have air raid drills, all the children had to come out of the classroom and sit in the center hall, the hallway, and I would serenade the children. I remember, I think it was Armistice Day or Memorial Day program at P.S. 31 in the current building, and I was singing. And there was a tough lady, Mrs. Murrin [phonetic], she was tough, the principal, she said, “You hear that boy, listen to that boy singing. Hear that boy?” [Laughs] There were some things that you just never forget, it has such an impression on you.

But one day I was sitting in the class and a woman came and took me out of the classroom, it happened several times, and she interviewed me and whatnot. My grandmother and I had to go to 110 Livingstone Street in Brooklyn to the Board of Education. I can’t tell you what transpired. Back to Bayside we came, and I was sitting in the classroom and one day somebody, a person or a student, came and got me and took me out of the room. And at that time P.S. 31 had what’s called an Opportunity Class, where children learn to work with their hands because they didn’t have it up here. They did beautiful work. The teacher’s name was Mrs. Pizer [phonetic]. And I was pushed over about two or three grades, and the next thing I knew I was graduating. They called it 6B at the time. And I went from P.S. 31 to P.S. 162.

Q: Were you going to school with African American and white kids?

Tshaka: Yes, it was mixed.

Q: And was the—?

Tshaka: We got along.

Q: It was good.

Tshaka: Got along fine.

Q: In the neighborhood and at school as well?

Tshaka: There was never any issue of race, none whatsoever. There was somewhat south of 48th Avenue, what we call Rocky Hill Road, it was rather Italian and I know the Buffen [phonetic] family got in there, moved and bought property. Well, Mrs. Buffen was light skinned so she came forward and bought the property, and this was during World War II, after World War II. And then when she came, her husband came, he’s chocolate brown and grandpop and they were [uncealr] but they all blended together. But down here, this is Matinecock land. Do you know what that means?

Q: It was a Native tribe.

Tshaka: Yeah. But the topography is hilly. Now when you go out on the street, and you look up this way, you see how high what they call Bell Boulevard is up there. And if you stand across the street at Bell and look this way, you cannot see the roof of the houses here, it’s that low. At 48th Avenue and Rocky Hill Road, the houses are high. And as you look at the topography again, Oceania is climbing to get to Northern Boulevard. At 206th Street, gradually climbing to get to the Northern Boulevard and it’s that way. I remember in 1937, there was a hurricane and I remember standing in the front door and people were going past my home here in rowboats and hip boots, going to the village. At that time, the city put in a storm sewer in front of the house here and, if I’m not mistaken, all the way down to the bay area and the water goes out to the Long Island Sound. Um, what else can I think to say?

When my voice was changing—I used to have a dog named Prince and I would go down to Oakland Lake, which is down near Springfield beginning at 48thAvenue, or whatever, there’s a big lake there. I was told that once upon a time the lake was channeling water into Flushing, spring water. And the water was nice and cold. I would be on the right-hand side and I would get halfway across and there was like an echo and I would try my new singing voice out and I would drink the spring water. Precious memories, how they linger and how they flood my soul.

There was a woman when I went to basic high school. Her name was Mrs. Waldire [phonetic], Gertrude Waldire, and she lived above the lake. And when she made her transition, I was able to get the walkway—because it’s just a hill of dirt—they made it Gertrude Waldire’s Promenade, Gertrude and Ted Waldire’s Promenade, and that was because of me. And on and on. What else can I say?

I was an equestrian. There was a horse stable up the street at 204th Street and 46th Avenue, the Bayside Stables. I used to take care of horses. Seemingly, I always had a good relationship with Caucasians. One day I was looking for my father who lived on the next block. As I said there was no Clearview Expressway. It was a Sunday and at the time, I used to wear knickers, and he wasn’t there. So something drew me going west and there was this big open field and when I looked there were horses over here going around the paddock with people riding them. And I ran over there and every Sunday I would go by, or Saturday, to look at the horses. There were two doctors—didn’t know they were doctors at the time—and they were renting two horses, Lindy and Bayberry. Dr. Crawford had Bayberry and Dr. Wheatley had Lindy. And one day I’m standing at the fence, it was a Sunday, he says, “Go ahead and open that gate and go up on that stand there and I’ll put you up on the horse’s back and I’ll walk you around.” And she did exactly like she said. And I got so that I could ride the mare around the yard, English saddle, on my own.

Then there is the Yuller [phonetic] family. I called them my brother and sister. They were very close to me. They had a beautiful horse—the father did—Golden Chap. And Mr. Yuller, Henry Yuller, said that I could ride him anytime I wanted to. I used to take care of Goldie.

I don’t know if I should tell you this or not. I still had a full head of hair and it started snowing, so we were going down and I put the saddle, the tack on the horse, and I got on him and I was going down Oceania Street going to Cunningham Park up there. And we got a block from Horace Harding, and there was a garden center there, and I saw a big white man come to the fence—and you’re going to fall on the floor when you hear this. He said, “I just had to stop you and talk to you. You look so pretty with the snow falling in your hair, riding that beautiful horse.” His name was Leo Schreecamp [phonetic]. And he said that he knew my grandfather when I told him my name, because I hadn’t become Mandingo at the time. He said, “I knew him, your grandfather.” I said, “You did?” He said, “Yes, he used to plow for me and they wouldn’t give him any liquor or anything like that because he was an Indian.”

And you could see Uncle Henry, grandma, Skank’s son, you could see that he was light, and Willy was up the street. And grandma was chocolate brown and I came across—somewhere I’ve got a picture of Mr. Skank, my great grandfather, and he was in uniform in World War I.

Q: So you had Indian, African American, Dutch, white.

Tshaka: Yes, Europeans.

A lot of people don’t know this—you’re a Caucasian—well, before that, the Africans were in Europe. Maybe you do know this. And there was no people called whites or Caucasians. But the great Ice Age came, and it went on for thousands of years and there’s—the anatomy changed. The African’s anatomy is: the nostrils are wide, the skin is dark, their hair is kinky, and there’s a reason for that. I heard that many people who were Europeans when they go to Africa if they stay long, they burn or they die. Their nostrils were wide that’s to cool the body off. And the hair retained the perspiration, which cooled the brain off. Whereas when they this became genetically recessive that changed, that they looked like you. Your nostrils are pinched, narrow, that’s to keep the heat in your body. To have—your hair is stringy or straight and it would have been death if you kept your hair kinky and it would not have worked, so your hair is that way.

I used to be an artist model at Pratt Institute and I had my back, I’m standing in a jock strap—I think it was all girls—and the instructor was going around the classroom, because they were drawing me, and he said, “No, no, that’s not right.” He said, “They’re different than us.” So I was curious, what was he talking about? And what he was talking about the anatomy that the African’s legs—and you’re going to notice this now—from the feet to the knees and from the knees to the hip, it’s balanced. But the Europeans, their thighbone is longer and the lower leg is shorter. And where you can really see this when you see these young Korean girls or Chinese girls going down the street with these tight leotards, you can really see it. The thigh is long and the lower leg is shorter. Yes.

But here we all got along. Often times we lived on the same property, same building.

Q: Nice. Tell me, how did you get interested in African American history and preservation?

Tshaka: Well, it wasn’t taught, you see. [Laughs] You’re going to fall on the floor when you hear this. Every morning at P.S. 31, we had to stand up to salute the flag. “I pledge alliance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible with liberty and justice for all.” Well, that wasn’t true, not for my people. And we were segregated, didn’t get justice, didn’t have that liberty. Even when the wars came, they mistreated us. World War II—there’s a documentary, every once in a while it pops up, and it shows that the German war prisoners that were brought here they had more rights—

[INTERRUPTION]

—civil rights, human rights than us. The brothers who were guarding them, when the Germans wanted to go to the commissary, they could go into the white commissary, but the brothers had to stand outside.

State Senator, [Frank] Padavan, the last time he was sworn in, he wanted me to—asked me to sing the Star Spangled Banner. I said, “I don’t sing that song. I don’t salute that flag. Ask me if you would like me to sing something else, I’d be glad to.” He said, “Fine.” Because I just can’t do it, and wouldn’t do it. For me, it would be hypocritical.

Q: What did you sing?

Tshaka: It was a hymn. I can’t think of it at the moment, but I’ll come back to that.

Q: So how did you come to learn about the injustice that was happening?

Tshaka: Well, it was very visible. As a little boy in World War II—it wasn’t here, had no problems here—my grandmother was going back home, down home to Suffolk, Virginia at Christmas time. And we met in Penn Station, the real Penn Station, the original. And there was a lot of hustle and bustle and people in uniforms and whatnot to get the train, and relatives brought gifts. And we got on the train I guess around 12:30 or whatever it was. We arrived in Union Station around 5:00 a.m. And as we got off the train—because we sat where we wanted, they had steam engines. [Makes the sound of the steam] And the Caucasian conductor had a lantern, “Colored, colored in the rear. Colored, colored in the rear.” And it didn’t matter if you were in uniform or not, you were supposed to go back in that back. My grandmother said, “I ain’t going to get in that cubby hole.” She was something. And where Nanna went, we went. So we walked right across the platform, up into a coach, and it was all males, European males, Caucasian males. We sat down. I like to sit at a window and watch the scenery go by.

When I awakened—I went to sleep that is—when I awakened she said, “You got to go to the bathroom, you better drink it.” I said,“Why?” “Because we’re sitting in the white folks coach, we’re not supposed to be here, and I just had an argument with the old conductor. He told me the colored were to go in the rear. And I told him that I bought my ticket at Penn Station just like everyone else and it didn’t say where I was supposed sit. And if he didn’t like it he could pull the cord now or put us off at the next stop. And God sent a young white angel who said, ‘Oh, leave her alone, Conductor.’” And she said that when they left the Caucasian man took our gifts and put them on the rack above where we were sitting. And said, “If more of your people would do this, you would break the back of Jim Crow.” She jumped Rosa Parks 20, 30 years. She was extraordinary.

But as I was telling you about the baby picture of me—when I look back at it, and as I was saying you’ll understand it better by and by. Like I told you, my mother had tuberculosis and my sister died. I was born on the 12th of May 1931. She died on the 25th of May, tuberculosis. And there I am just as strong looking and I’m still here. And so often, that track switches. So they might not know what I’m talking about track, like railroad tracks. The old railroad tracks when they were not automatic like they are now, when they were going somewhere they had to veer off. The train would slow down, the engineer would get off, put a rod in the tracks and pull the rod and the tracks would switch over. That’s just how my life is, because I’ve been on that straight go. Where I was going I would have been dead.

One of the most classic examples of that is my father had a construction business, and his specialty was digging—wait till you hear this—cesspools, dry wells, sewer lines, cement, gardening, whatever it was. And we had a cousin that worked over in College Point in New York City and he worked for a florist. He was Native American, mixed, and he liked horses, too. And he got my father a job because the owners of the hot house, wanted to hook their hot houses into the city sewer. So he went over there and looked at it. The hot house was like here, there was nothing obstructing it out to the street. So he got a crane or a backhoe to dig out the trench right up to the buildings. A big gap in the middle of the street. It rained the night before. I wasn’t home. Like all creatures eventually they leave the nest and fly away, may come back. And I was living on Smart Street with the same family I was living with when I was a little boy, on 4536 Smart Street in Flushing. And we drove over there and the dirt was piled on both sides of the open trench and a big gap in the middle of the street. And there was a fellow named Reevis, they called him Red Reevis, and he was in the trench. And as I walked up to the open gap with—like where this archway is, the doorway here, or let’s say that doorway there, yeah. So the trench was maybe about as wide as that doorway I’m going to say.

Q: So like three feet.

Tshaka: And then I noticed out in the big street there was a slight hair crack in the wall and the dirt was above it. So we got down in the trench. My father was in the middle of the street, I was by the opening of the trench and Red was behind me, and we were throwing this mud out. And every time I would move my foot, the suction was so great, it was pulling my rubber boots off. I was complaining and my father said, “All right, I’ll switch with you.” So I switched with my father. Now I’m in the middle of the street he’s standing where I was in the trench. I said, “Watch out for that crack.” “Oh, it’s nothing to worry about.” Give it two hours or so, that whole thing came down and hit him in the head, fractured his skull and he’s buried over in Flushing Cemetery.

Q: This is your dad?

Tshaka: Yes! And I was standing in the same spot. And what I’m saying to you is—I get chills when I tell this—that it was all pre-laid out for me to do the things I did. I didn’t know it. But if I had been on that straight track, I would have been dead. But God always pulls that rod or something, and pulls that rod and saves me.

Q: How old were you when that happened?

Tshaka: Well, it was ‘58, so you do some quick math. I was born in ‘31.

Q: Okay, 27.

Tshaka: Mm-hmm. He’s buried over in Flushing Cemetery. And time and again—I have a Hoveround chair. There’s something strange [laughs]—there is Corporal Kennedy and Northern Boulevard. Now I have a poster here, which I’ll show you. It’s advertising my life story, my book.

Q: Oh, I saw that you wrote a memoir.

Tshaka: Yeah, that’s the advertisement.

Q: That’s great.

Tshaka: So I got on my scooter and I took the bus. What is the most amazing is when I come with the scooter or chair everybody has got to back up. I get on first. It’s almost like I’ve got bad breath or body odor. [Laughter]

Q: [Laughs] Or respect.

Tshaka: No, but they have—because they have to lift the seats up you see.

Q: Sure.

Tshaka: But everybody is moving back. If they’re seated, they’re moving back. [Laughs] So what else was I going to say?

Q: You were going somewhere about the book.

Tshaka: Oh, yeah, I went to Macedonia A.M.E. Church in Flushing located on Union Street and 37th Avenue to give them the poster, and got the bus and came back to Bayside, Bay Terrance. While I’m at Waldbaum’s, I noticed that the battery was getting weak. I made it to Bell Avenue, or Bell Boulevard or Avenue—of course that’s what it is—and I was able to get up into the bus. And there was an African American woman driving the bus. I told her where I get off. She let me off and I came to the corner and the light changed, and I got in the middle of Northern Boulevard, the traffic coming at me, and the thing had a massive heart attack. And I’m trying to put my feet to get this thing to move and God sent an angel and I heard a voice, “I can’t leave you here like this.” It was the bus driver and she pushed me up on the sidewalk.

Another time at the same site—my, my, my—it was pouring rain on a Saturday. The chair was working beautifully, and out of nowhere I heard a voice from heaven say, “Here, you take this, you keep this.” And I looked and I don’t know if he was Chinese or Korean, a young fellow, handed me an umbrella. It’s in the back there.

And then another time, the chair, same spot, crossing Northern Boulevard, the chair had a massive heart attack, and threw me face down in the street. Now when the bus pulled up to the curb it was hard to squeeze into the curb and the 111th Precinct has—there’s a police officer, is, was, an African American fellow—I’d heard about him—he was there issuing tickets in his plain car. And I got off the bus and I saw him go to his car. I said, “I’m going to need you to help me across the street.” He looked at me and never said nothing. So I’m thinking he’s going to come and again it had a heart attack, the chair threw me down the street, face down, on Northern Boulevard. Now I don’t remember him coming, but God sent another Asian fellow, come to find he was Chinese, he helped me get up, pulled me back and pushed me all the way from up there to my backyard.

And so often—there’s a family, they live on the corner of Oceania and 45th Road, the first attached house like these over here. Not this one. And usually Jimmy and Tanya are in their yard facing this way. But as I came down the hill, strangely they were on the sidewalk sitting looking at their home. And I got to the bottom of the hill and the motor cut off and threw me out there face down on 45th Road and the two angels came over and helped me get up, Tanya and Jimmy. I have never seen them again. There are just so many things that happened to me, that it’s a calling. It’s a calling. I have to say on high there is—now I talk my trash, don’t misunderstand me. [Laughter] I talk my trash, I do.

There was a fellow named Jonas and about thirty-some years ago, he said to me, “Mr. Mandingo.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “You act like you’re walking straight down the line.” I said, “I’m glad you see that because I don’t go too far to the right and I don’t go too far to the left.”

And this area it didn’t look like it does now, street wise. When I came home there was young fellows sitting on the corner by 158 School at Oceania in summer chairs, selling crack. And nobody was saying nothing.

Q: In the ‘80s, was this in the ‘80s?

Tshaka: Mm-hmm. Selling crack on the corner there. The families—it stood out and none of the parents said anything, none of the so-called men. I don’t know if I should say this—[laughs] the one that they would call gay or whatever, he stood up and changed the whole damn thing.

Q: That would be you?

Tshaka: Yeah. Yes. I didn’t choose to be that way. Speaking on that subject, when I would go downtown—I’ll come back to Bayside in a minute—when I would go downtown to City Hall to fight for this neighborhood—and what started me—let me come back again. There was a lady named Mrs. Grace Cunningham. She lived on Oceania Street here across the street from the school, between 46th Avenue and 46th Boulevard. She said, “Jim.” I said, “Yes, Mrs. Cunningham.” “Somebody ought to do something about people on this lot.” “Well, what’s the problem?” “Well, Helen’s brother’s Mercedes Benz bought it, tore down the houses and he wants to put cars over there. It’s just not right. Somebody ought to do something about it.” I knew nothing what she was talking about. But God guided me to the room in the back there and I got my old typewriter and I plucked out what I called a petition, pluck, pluck, pluck. And I went around on the 45th Road and I was surprised to see people were signing it.

Q: And what did the petition call for?

Tshaka: To oppose the expansion they wanted to put over there. It’s residential property. But I didn’t really even understand that because it was just properties. Mercedes Benz the—I didn’t know anything about zoning. So, anyway, everything was going along fine till I got to 206th Street, around the corner here between 46th Avenue and 45th Drive. Mr. Leroy Watkins was an educator. He looked at it and said, “This isn’t right,” but he signed it. And that case went all the way up to the New York State’s Court of Appeals. Then Borough President—wait till you hear this—Donald Manes was the borough president of Queens. He supported it.

Q: And when was this roughly?

Tshaka: Early—late ‘70s, early ‘80s. And, my, my, my. As I said the Court of Appeal’s based their decision upon the current zoning resolution and that is to grant a variance within the City of New York the property must be physically unique, narrow, shallow, irregular— and this isn’t. It says there is nothing to distinguish this lot from all the others. It’s neither narrow, it’s not shallow, it’s rectangular, and the lot is vacant till this very day. Then Donald Manes wouldn’t support me again. His brother, Morton Manes, was leasing property to Mercedes Benz across the street.

At that time, the New York City had—there was the Building Department and the Board of Standard Appeals and then the Board of Estimate, which could overturn the decisions. And once a month, the five borough presidents, the comptroller and the mayor would meet at City Hall. Well, I went there, I opposed it, and Mercedes Benz spoke. Then the chairperson said, “We’re going to close this meeting for a moment and go back and discuss if we’re going to approve or disapprove.” And I saw people going in the back who I felt shouldn’t have gone. When they came out they supported Mercedes Benz. So unbeknownst to me—I speak to the Bayside Times about what I saw. Headline said, “Tshaka accuses Manes of a conflict of interest at the Board of Estimate.”

Early one morning, my telephone rang and it said Donald Manes cut his wrists at Shea Stadium and then he went home and committed hara-kiri. Gabe Pressman came out here and interviewed me and the last thing Gabe said to me was, “You be careful. Do you hear me, you be careful.” I get chills. You hear the hymn “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost but now I’m found. Was blind but now I see.” I see that it’s a calling that I have.

Q: And was that your first time sort of in activism?

Tshaka: The first was the lot. That was it.

Q: Right.

Tshaka: From then on, I became more astute and I learned that the federal government and its racism had wrote this area off as borderline property. We had the same old country streets, no sidewalks, no curbs, and then I learned there was CD funds, Community Development funds, federal. And the first street that got put in was one block from Northern Boulevard, sidewalks and curbs from 206th Street or Clearview Expressway up to Bell Avenue, they call it Boulevard. And the city had even dumped the sanitation garage over here, up there. They would do that nowhere else. I’d go up there and pitch a bam-doodle. And one day I was at City Hall and they announced that the Sanitation Department was going to be removed, the garage was going to be moved, to Winchester Boulevard. That’s over by Creedmoor. And it was. Please don’t think I’m bragging or boasting but there are—many are called but only a few are chosen and evidently I’ve been chosen to do these things. It’s so clear.

Q: Tell me about the burial ground, the Olde Towne—what’s now called the Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground.

Tshaka: Okay.

Q: How did you first hear about it?

Tshaka: Again, I find that during conversations—

Q: I’m listening.

Tshaka: I find that during conversations with me, unbeknown to myself and others, that it’s said for me to hear. I’m a member of the Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal Church, which is the third oldest religion in Flushing. Now Flushing, once upon a time, incorporated out here. The first is the Quaker Meeting House, St. George’s Episcopal Church and then Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal Church. I was chairman for Men’s Day. We were just having a meeting of the men and out of nowhere a fellow said, “Jay’s got relatives buried in the park across the street from Flushing Cemetery.” I heard and I didn’t hear it. And then there was another meeting in Matinecock, indigenous people had a meeting at Macedonia, and a woman named Penny said the same thing, and she said that his last name was Williams.

And so then there was a burial service at Macedonia for the princess of the Matinecock and she was to be buried in Flushing Cemetery. We arrived at Flushing Cemetery late and so the gravediggers were out to lunch, so we had to sit there and wait. So I remember as a child going past Flushing Cemetery and we were visiting our family you would hear the chimes playing hymns that I heard in church. So I go down there, “Would you please play the chimes?” They said, “We don’t play them no more,” they’re broke or whatever. And as I was leaving, I had an epiphany and asked about across the street, because there was a playground over there, Marie Curie Playground. And I said, “Pardon me, did you ever hear about a cemetery across the street in that playground?” He said, “Yes, just a minute.” And he went in the back and came back with a book and turned some pages and there was it was, The Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground. 164th Street, 165th Street, 46th Avenue and on the south side is Flushing Cemetery. And it showed that there was four burials, babies, and they had headstones. Three Bunns and a Curry child, Willie Curie.

I said, “May I have a copy of this?” And he said, “Sure.” And I noticed that it was the Queens Public Library published it. So I went to the main library in Jamaica. Wait till you hear this. So I walked up to the desk and I said, “Do you have any information about The Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground?” And the woman behind the desk, she said, “Yes. Reach up on that shelf up there and give this man that cardboard box.” It was just like that.

Q: And when was this about?

Tshaka: About the burial ground.

Q: No, but what year was that happening?

Tshaka: Maybe 1980, something like that. I don’t know. And I went into where I could read this thing. There was so much information about this burial ground, how they put people in shallow graves. And one fellow was doing some work and the casket gave way under his feet and he fell onto another grave. This one thing—[Robert Moses], I think it was, he was the [Commissioner] of the Parks Department. Nothing but racism, because you see where they dug up the burial ground just around the corner is Kissena Park, about four blocks away. There wasn’t any need to have a playground, particularly back in 1935. They dug up remains, left them exposed. The pennies that people put on people’s eyes because they probably were not being embalmed, and they were stealing that, WPA workers. They desecrated the graves. They put a park house in there, a wading pool, swings, all those things. So I took that and it ended up in the Supreme Court over in Brooklyn. And then God sent another angel, John Liu. He was the councilman. And because of him we were able to get it done, reclaimed.

Q: So tell me a little bit more about that. Had the neighborhood—? you said you learned about it from some church members at the A.M.E. Had most people forgotten that history or maybe never knew it?

Tshaka: Well, the sad part is, I was raised in that church and never heard anything like that. People were going to Flushing Cemetery. And if you know Flushing Cemetery—somewhere I heard that where 46th Avenue is, what they called Rocky Hill Road at the time, that was the back of the cemetery. Now they’ve transferred it and the offices now are abutting 46th Avenue. Do you know where I’m talking about?

Q: Not so clearly.

Tshaka: Okay. That’s now the main entrance. So the Caucasians, the majority of them are to the south. Even I will be buried along the segregated area of 46th Avenue. My headstone is already in there. The reason I got a headstone: my sister, Grace is buried there, she was a baby, and then my grandmother buried a friend of ours, Irene Wilson, with her. And due to the fact that my sister was a baby, they can dump me in there, so I got the headstone. It’s already there. And Louis Armstrong is buried back up in there.

Q: Mm-hmm. So when you learned about the old burial ground, what happened before John Liu arrived? I know there is a conservancy. Did you help to start that?

Tshaka: Yeah, I started that. I was with that, and then a woman named—my mind isn’t working—just bear with me for a second. Can you cut that out for a second?

Q: Sure.

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: I met a woman named Robbie Garrison at one of the meetings at Macedonia. We were selling history books and whatnot. I met her and we became very close, so she worked along with me.

Q: To establish the conservancy?

Tshaka: Mm-hmm.

Q: And when was that about?

Tshaka: About 20 years ago, I guess it is now.

Q: Okay. And how did you go about doing that?

Tshaka: Just had a meeting and talking about it. Just started meeting and talking about it. We may have started it at Macedonia, if I remember correctly. My mind is not as sharp as it has been.

Q: It’s sharp. It’s sharp.

Tshaka: And then other people came along and joined.

Q: And what kinds of things did you do to try to re-establish the burial ground as a memorial site?

Tshaka: Well, we were meeting at the grammar school over there on 45th Avenue. We met there several times, because it was right in the backyard. And as I say, Councilmen John Liu came in and with his help and money—when they agreed to do what they’ve done already, they had—the records show that there are more than 1,000 people buried there. And members of Macedonia—Macedonia’s original property is not that big, maybe as wide as mine. And the town of Flushing administrative government was concerned about health reasons because they had a cemetery there. And if you ever go to Macedonia, that’s at 38th Avenue and Union Street, as you go up the stairs and you go through a large archway, and there’s a room, you see a picture of two men and a pit and a big bag of human remains. That’s when they were building the current sanctuary. And then Reverend Dawkins and Mr. Williams were there. Their remains were sent to Flushing Cemetery. See God moves in a mysterious way, as one is to perform. They wouldn’t accept the remains because they didn’t know who they were and they were brought back. And Reverend Dawkins had the remains re-interred in basement of the sanctuary. And, as I say, God moves in his own mysterious way.

Back in the ‘50s, the African American community was living there from let’s say Main Street to 38thAvenue, to 37th Avenue, to Union Street. We had our businesses there. We had barbershops, printing, Whiting’s Printing Press, Mahood’s Funeral Home, etc., etc. The church, the old educational school was there on 38th Avenue. They took eminent domain over and demolished it. They wanted to remove Macedonia, and a woman named Mabel Usher Whiting—her maiden name was Whiting—she was down at City Hall and someone asked her, “Did the church have a cemetery?” She said, “Yes.” And when that was brought out, everything stopped. And the church is there under the administrative code and they have been there since 1811 and they couldn’t touch it. So if you come along you’ll see that on—there’s a traditional shaped church and then the city gave them some land, the church, up on 37th Avenue to 38thAvenue, but they had to build a community center in a certain amount of time, and the church was able to do that.

Q: That’s terrific.

Tshaka: It is.

Q: So I read that in the ‘90s when the city was intending to renovate the playground that you did a lot of—

Tshaka: No, no, demolish.

Q: Okay.

Tshaka: Decimated.

Q: I read that you did a lot of work to get them to do an archeological survey.

Tshaka: Okay. They had the information but they—when they had removed the buildings, there was a woman—I’ve got her phone number here somewhere—that they had like a carpet sweeper go across the land. It’s just like the book said, they were buried in shallow graves helter-skelter. And the Europeans in Flushing, they had some kind of disease and the family members died and they didn’t want to put their deceased in with their other relatives so they dumped them in two separate pits, large pits, with the people they already disliked. And that all showed up.

Q: This was sometime in the ‘90s, right?

Tshaka: Yes. It all showed up just like the records were saying.

Q: So it’s a mix of white people who had small pox—

Tshaka: Disease.

Q: —or some disease.

Tshaka: Whatever it was, yeah.

Q: And then African Americans.

Tshaka: And Native Americans.

Q: And Native Americans.

Tshaka: And see, I don’t say Indians.

Q: And was it a playground into the ‘90s?

Tshaka: Okay. There was a playground there from 1935. Robert Moses was the commissioner, infamous Robert Moses.

Q: Yep.

Tshaka: They put up a park house, a wading pool, swings, seesaws and all those things there. And then they were playing ball in the back. I think it was on the lawn area. Mm-hmm. That was all demolished.

Q: And when was that demolished, was that—?

Tshaka: Dates, I can’t say, but you can check with the Parks Department. They can tell you that.

Q: Okay. And can you tell me about the effort to rename it back to the old name?

Tshaka: Well, it was called Towne Ground, Towne Burial Ground. And as I say, they gave members of Macedonia the right to bury their dead there, our dead. It became—it ended up with the Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground. But still, they are reluctant to replace the headstones.

Q: Can you tell me about that?

Tshaka: Yeah. According to Linda, what’s her name, at the Parks Department—I can’t think of her name now. She said that, “Oh no, you can’t put any heads—” the Parks Department, “You can’t put headstones in the park.” I said, “This is not a park or a playground; it’s a cemetery.” “Oh, no, no.” So they got a wall of bricks about that size.

Q: Like a regular brick.

Tshaka: Yeah. Thousands of them. They got two different—they stand about as high as that.

Q: So maybe two, three feet?

Tshaka: About three feet. And thousands of bricks and you could sit on a bench all day long and you would never see. And they etched the names of the four children in those ones. There are certain symbols. The Parks Department in did a beautiful job of obelisk and headstones. They said the Department of Design turned it down. Did you know that Sarah Roosevelt Park is an African American burial ground?

Q: I did not know that.

Tshaka: What have you heard about the African Burial Ground? City Hall was a killing ground. There is a sign that says this. Robert Moses wanted to place a replica of the original fence, which the original fence is upstate around a cemetery. They had to stop it because they hit remains at City Hall. They were doing some work at Boss Tweeds Court House. Con Edison had to stop because they hit human remains. Slavery was here in New York. The Dutch brought the Africans here first. The Africans asked the Dutch—they were not as vicious as the British—for some land. So they gave the enslaved Africans land from the Hudson River to the East River. And then back in the ‘90s or so, they came across human remains, or what they call the African Burial Ground. I went down there because of my involvement with the Burial Ground of Flushing. And there was a Caucasian woman coming out of the pit and she said, “Our information is,” when I spoke to her, “that this burial ground goes several blocks west.” So the city knows that those buildings are built on a cemetery of the Africans, the enslaved Africans.

The enslaved Africans became a buffer between the Dutch and the Iroquois. But as more of the Europeans invaded the area, the Africans were pushed north. The next burial ground is today called Sarah Roosevelt Park. The Irish were moved in there and they desecrated it, and then they made it into a playground. We were pushed again up to where Washington Square is. That’s a burial ground of enslaved Africans. Somewhere I have a book that says there were military exercises going on there and they would shoot the canons. The old canons would rise up and hit the ground and go into a grave. They were doing some work there with Washington Square recently, they had to stop because of why, they hit human remains. Bryant Park is another burial ground. They have a statue in the back of the library of a Caucasian sitting down. His historic thing is that he worked in the female sexual organs and was saying how they can tolerate so much pain. Then there’s Seneca Village. There’s a big exhibit in the New-York Historical Society up in Central Park. There are two burial grounds up there. The one in Flushing. And the Queens Commissioner of Parks, “Oh, no, you can’t do that. You can’t put any headstones in there,” but in Kissena Park they’ve got a memorial that they put over in Kissena Park about five years ago I think for the Vietnam War, or whatever it is. That memorial was not there for those who were living. And I must say the Parks Department did a beautiful design. Community Board Number 7 approved it.

Q: Of the burial ground in Flushing.

Tshaka: Yes. But the Department of Design or something said no. They wanted to put a wall up.

Q: Because the original design was going to be an obelisk and the four headstones back, right?

Tshaka: Yeah. They said, “On park land you can’t do that.” Okay. Go up to Washington Square where they’ve got a big memorial for whom—I mean, Columbus Square up there—a man who never came here. I don’t know why they have to celebrate Columbus Day. He never touched here. What they call the Dominican Republican, he bumped into that. And called the people here Indians. No, he was trying to get to India because Marco Polo made his trek from Italy into Cathay and China, or India and Cathay. When he returned he brought all the wonderful things, and spices or whatever it was. Europe wanted it they didn’t have it. But to get there—turn that globe around. Turn it up all the way. The other way. Easy, easy, now. Easy, easy.

Q: This is beautiful.

Tshaka: Okay, you see Africa? Now turn it towards you. Okay, the Atlantic Ocean. Stop, stop, stop. They would have to come all the way around the Atlantic Ocean, go around—turn it back towards me—around the Cape of Good Hope and up to what they called the Indian Ocean, and it was so long. So they were trying to find a shorter route. And Marco Polo—or Christopher Columbus—somewhere I read that he made a trek into Africa with the Portuguese and he saw the Africans going out into the Atlantic ocean and coming back. I hear there’s a strong current that pulls you west. And they were bringing different items in. So he persuaded Isabelle and Ferdinand to give him those three ships. And he trekked off and he bumped into the Isle of Hispaniola, they call it, Dominican Republic and Haiti. He brought some of the indigenous people back, claiming that he had reached India. And that’s why today they’re called Indians, but they’re not. The Indians are just getting here.

Q: So let me ask you—let’s come back to the burial ground—do you feel that people know about it now?

Tshaka: No, not like they should. You know why? When you go to—I’m going to tell you how—you’re going back to the Flushing, right? I’m going to tell you to take the bus, the 27 bus over here, and I take it right down there. Tell them to let you off at 164th Street and 46th Avenue. You see the ambulances, the New York Hospital ambulances. It’s right there. Flushing Cemetery is across the street. When you look across the street or as you come down, you can’t deny that that’s a cemetery. But when you come to this side, on 164th and 165th Street, it looks like a park. None of the symbols are there. None of the symbols. And they said, “Oh Parks Department, you can’t do that.” Okay. Then my question is down on Northern Boulevard, Flushing between Main Street and Union Street, from a boy there were all those obelisk and memorials there for one of the wars, World War I or whatever it was. They’re there. You come—oh, I got chills—you’re coming this way on Northern Boulevard East you get to the Clearview Expressway and Northern Boulevard. On the northeast corner, there’s an obelisk with wreaths and names, on park land. So what’s this—? I’m being nice now. What are you talking about? If I’m not mistaken, there’s an obelisk in Central Park that belonged to Cleopatra or something that they put in recently.

Q: Mm-hmm.

Tshaka: So I’m saying what are you talking about?

Q: Do kids learn about the burial ground in some way? Is there any way for kids to—?

Tshaka: Here goes, if the—in Brooklyn, I think it is, they have a memorial area for the Jews who were desecrated and murdered in World War II. But they got more—there are signs about this high, with the names of the people on it. If they can do that on there, why can’t you put some headstones over here? They’re talking about putting a wall up. When you go by you would never know. It looks like another park. In fact, we’re going to start getting the NAACP and the Urban League involved with this.

Q: To change the renovation.

Tshaka: To put some pressure on the city, the state. It’s nothing but racism. Yes. It’s nothing but racism again, alive and well.

Q: Yeah. Are there places in the city where African American memorial sites are paid their due respect, do you think?

Tshaka: No, not that I know of. I told you about Washington Square, Sarah Roosevelt Park, Bryant Park. The Waldorf Astoria is built on a burial ground. And Seneca Village, you would never know that in Central Park, the average person, that there are two burial grounds there. We were pushed out. We were always—as more Europeans came, we were pushed more north and we were pushed out of there.

Q: So what is your hope for the burial ground with the NAACP and—?

Tshaka: That the right symbols be put in there so that when you see it, you know what it is. And they don’t maintain it that well. I went by—I was going to my doctor, Access-A-Ride when we past Kissena, beautifully maintained, beautifully landscaped and whatnot, beautifully manicured. This site—even in death—pardon what I want to say—a black man and woman has no rights, which a white man is bound to respect. You see it. Now this is not for everybody, but the people who are in charge, they look like you, Caucasians. I mean it’s just a doggone shame.

Q: An outrage.

Tshaka: Yes, it is. And then they say, “Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord.” [Laughs] The other ones: “I ran to the rock to hide my face and the rock cried out, ‘Ain’t no hiding place down here.’” This country would never have—we didn’t do the work here because we wanted to, but without the enslaved Africans, they would never have achieved what they have achieved. Forced labor.

Q: I know.

Tshaka: I have friends that are in South Carolina, and Ku Klux Klan was out there—last week I think I saw—raising hell. The Africans didn’t do anything to them. It’s what their ancestors did. But I have to say this area here—it’s a funny thing, I was at CVS drugstore, about two months ago, and I was waiting in line. There was a man in front of me. He was not dressed in any particular attire but there was something about him that was different. I said, “Pardon me, are you a minister or a priest?” He said, “Yes, I’m the priest for the Polish Catholic Church on 35th Avenue.” So I said, “They used to call this area—” he said, “Pollock Alley.” [Laughs] And I’m telling you, we got beautifully along with the people here. The Asians are coming in now. Lord, they’re busy, but nice people. See there are good people and negative people and hateful people in all groups. Yes. So I don’t know if this helps you in any way.

Q: It did. I have a couple of more questions.

Tshaka: Mm-hmm.

Q: So even though the work of the burial ground is not done, you have accomplished, I think, a lot in getting the playground out and in renaming it and in some kind of memorial.

Tshaka: Yeah.

Q: So what advice, if any, do you have for other New Yorkers who have buildings or neighborhoods that it’s important to save and remember and preserve their history? What do they need to know or think about?

Tshaka: They need to know the history of the site, and then you have to get to the politicians.

Q: And how do you do that?

Tshaka: You need to approach them, and invite them, and so forth, and pull their pants down in the press. It went to the press. They need to get people to garner together. It’s interesting, garner, [laughs] a lot of people don’t know what it means. Garner means to gather. Yes, that’s what they need to do.

And then—and please don’t think I’m bragging or boasting—many are called, but only a few are chosen. And when I’m looking back at these baby pictures and whatnot how—like here, there I am sitting up there just as strong with my little dress on. My mother was upstate, tuberculosis, and my sister died on the 25th of May 1935, tuberculosis, and there I am just as healthy. And so often that—it’s a calling or something. Protection. I have been very, very protected, divinely protected. At the moment I didn’t understand it but as the song says, you’ll understand it better by and by. When I look back at this journey that I’m in it’s—it’s really unique.

Like I was going to tell you about 42nd Street, when I would leave here to go downtown to fight for the community, take the transportation, the bus, the train, the subway to Times Square, downtown to City Hall, and coming back. I come to 42ndStreet Sodom and Gomorrah, and upstairs I go to see what’s going on. And one evening I came out of the building, one of the buildings or whatever it was, it had gotten dark earlier, as I said it before, and it wasn’t cold. I had an epiphany. And the voice said within me, “You can’t do this no more. You know, it would be just your luck to be coming out of one of these places, and somebody is doing a documentary on what’s going on down here and you would be a prime candidate for a camera.” I remember looking down at 8th Avenue and back, nothing seemed to be going on. The voice spoke again, “You can’t do this no more. You know Donald Manes is upset with you because you accused him of conflict of interest at the Board of Estimate. The business people are upset with you because they are claiming that you are interfering with the way they are making their living. The 111th Precinct is upset is upset with you because you are saying that they’re not doing their job in the neighborhood where you live. The community is upset with you because your change of the lifestyle there. They’re just waiting for you to make a mistake.” And I heard that voice speaking to me and I haven’t been down to 42ndStreet anymore. But there was something else. ‘81, ‘82, two new entities hit this planet, HIV and AIDS. Do I look sick?

Q: No.

Tshaka: Yes. And so many didn’t get that message, or if they did they didn’t understand it. I would haven’t have understood either. But I did understand that voice about don’t go down there no more. And I’ll tell anyone, everybody in his or her life if they could get around, they’ve stepped in urine and ca-ca. [Laughter] And it’s true.

Q: You’re cleaning up your language for me I think. [Laughing]

Tshaka: Well, you know, there are some things that you—you know I know other language, but you understand what I’m saying.

Q: I do.

Tshaka: We all have had our wild days. And I have to say—I get chills—for me it’s amazing grace that I’m here. Many are called but only a few are chosen, and I don’t play with it. Oh, I talk my nonsense. But as humanly possible—and you hear how this house is?

Q: It’s lovely.

Tshaka: That’s how it is. And when I come down the street, you can feel the air change, as old as I am. And when I go up to Bell Boulevard—this is unique [laughs]—Caucasian women are kissing me. There is a fellow [laughs], his mother lives on Bell and he lives down the street, he sees me, “You good looking bitch, come over here and give me a kiss.” [Laughter] I was at the CVS drugstore about two months ago and he walked right up to me and gave me a kiss, and that’s just how it is. Bayside is one of a kind. And I truly am. I didn’t choose it. It was divinely given. And I tell when I go down the street, you can feel the atmosphere change, old as I am. It’s just amazing. When we had the crack, one house on this block, they were shooting fireworks at me. Do you remember the movie Shogun?

Q: Mm-hmm.

Tshaka: It was playing. I was in my bedroom. It was a series. And one night I heard, errrr, boom, errrr. I said, “Damn, it’s not the 4th of July!” So I got up and went to the front door and looked across the street. You could see the doors across the street, the front doors, adults standing there and they’re shooting fireworks. I said, “Please don’t do that.” I said, “One of them could get up on my roof and it could start a fire. And none of you are going to say you did it.” And the fellow had a bottle and he was shooting it over here. I said, “I asked you not to do that.” The son came over, he lit a firework by the driveway over there and he snuck on back. So they shot another one. I said, “Oh, you want to play with fire? Goddamn it, let’s play with fire.” I went to that china closet there and got my great grandma’s kerosene lamp that had had no fire since 1940 when she passed. I took the shade off, turned the wick up, and lit a match and it said, “Oh, I’m so hungry! Where have you been?” [Laughs] I stepped outside there wasn’t a living ca-ca out there in the street. There wasn’t a living ass out in the street, from 206 Street to Bell. And I walked over to that house in my bare feet and I said, “I begged you, I pleaded you not to shoot those fireworks. But you want to play with fire? Well, goddamn it, let’s play with fire. If you ever shoot another one over here—you see this kerosene lamp? I’m going to walk over here—and see that big window? I’m going to cast it in there and make sure it burns your house down.” “Oh, Jimmy said he’s going to burn the house down.” And his father said, “He ain’t going to do it.” I said, “I pleaded with you, your family, not to shoot any fireworks at me. And just as sure I’m standing here with this kerosene lamp if they ever shoot another one I’m going to burn your house down. And I’m going to start walking toward the 111th precinct. If you feel you must call them, you tell them Mr. Mandingo said open up the cell door and he’s going on in and slam it.” I had no more problems.

I got—see these sidewalks and curbs? It’s because of me. We didn’t have any sidewalks, any curbs. That’s right.

Q: So let me ask you—you have so much of your own history here—have you given any thought to archiving your own records and your memorials? Do you have a plan for how to save them?

Tshaka: I have a book, my life story. Where is it?

Q: I’ve seen it online. But what about all your proclamations and the papers from your preservation work?

Tshaka: I guess I’ll have to send it to the Bayside Historical Society. By the way, they put a plaque up about me at the Bayside Historical Society.

Q: Nice.

Tshaka: It is quite a journey. I think it’s, I guess you would say unique. I’ll tell you one more thing, I told you how I failed at school, and there was a woman named Mrs. Streeter [phonetic] and she was very active in P.S. 31. She had a son named Ned and Francis. And I was at the Chase Bank where it used to be on Bell Boulevard, Bell Avenue, and I was in the vault area. And Mrs. Compsal [phonetic] who is charge of the vault said, “Oh, there’s Mrs. Streeter.” And I looked and here was that woman from P.S. 31. So I walked over and said, “Hello, Mrs. Streeter.” I didn’t use the name Mandingo. I said, “My name is James Garner.” She said, “Oh, I remember you.” I said, “You do?” She said, “Yes.” Wait till you here this. “It was I who signed the papers for you to graduate.” [Pause]

And when I went to Albany in 2011, about 20 people went with me. It’s just—it’s really a blessing. Who would have ever thought that would have happened through a phone call. I was watching—I had colitis, in the New York Hospital, and there’s a hymn that says, “There is a fountain filled with blood.” Well, I can’t tell you about that fountain but I can tell you about toilet bowls being filled up with blood. And Ronald Reagan had passed away and they brought his remains back to the Capitol. I’m watching on television and the military choreography was beautiful. I said, They’re always honoring these Caucasians but they never say anything about the African people. And I just read a book The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks by Randall Robinson. And I picked the telephone up and I called congress, Gary Ackerman’s office, which was up here at Springfield and Northern, and I told him what it was about. I swung over to Washington, D.C. In 2008, they opened up the Emancipation Hall in the Capitol and I was back here in 2011 I think it is, yes, when I was honored about that plaque there, which they put up.

Q: About making sure that it says in Capitol about slave labor helped build it.

Tshaka: Yes. And I got them to use the word not slaves, enslaved.

Q: Enslaved. Good.

Tshaka: Enslaved Africans did it. Yes. So that’s part of my story.

Q: That’s a big accomplishment.

Tshaka: Yes. Yes. I would never—John Lewis is over there, would never have thought of it.

Q: So that’s a photo of you and John Lewis and Ackerman.

Tshaka: That’s right.

Q: Both about putting the plaque up about enslaved labor and recognizing that you—

Tshaka: Yes, in the Capitol.

Q: —raised the issue.

Tshaka: In the Capital. And there’s a speech that he spoke before the House of Representatives about me.

Q: Giving you the recognition for your work.

Tshaka: Yes. Just I got accommodations, accommodations, proclamations. It’s quite a journey.

Q: That’s fabulous.

Tshaka: Quite, quite extraordinary journey.

Q: So before we say good-bye, is there anything else you want to share either about the burial ground, or about what it takes in New York to try to preserve history, or anything else?

Tshaka: Well, the old grey man, he ain’t what he used to be, you understand. I think my mind works pretty good. But physically—others would say, “Well, you’re 84.” No, I’m including nine months to be born and I jumped out there I was just as husky as could be. I was alive for nine months in my mother’s belly, so I say I’m 85. All I can say is, it’s a divine calling, a divine calling on my part. It would be wonderful if the New-York Historical Society was able to get involved, because it’s important history. When you look at the word history, it says his-story. It’s not really taught. The churches need to start telling the truth. I don’t know if you’re Jewish or not. Are you Jewish?

Q: I’m not.

Tshaka: Well, the day I was going to the Capitol, normally I would—no, was that the day? Yeah, I was going to the Capitol. See normally I would take the train. My cousin Connie Bunn, she—she got a bus.

Q: This is a picture of you and your cousin Connie?

Tshaka: My cousin.

Q: Nice.

Tshaka: And we loaded the bus at Cushing from Penn Station. I was ready to get the scooter in. And I sat at the stairs as you come up on the bus and someone said, “Now where are you from?” I told them where I was from. Then I heard somebody say to a fellow, “And where are you from?” And he said, “The holy land.” So I said, “Pardon me, what holy land are you speaking about?” “Israel. It’s my ancestral land.” “Are you saying your Jewish?” “Yes, yes, my ancestors.” I said, “Well, I’ve got news for you, you may be a Jew by conversion but not by blood. The original Jews are black.” And when I go to the Catholic churches all of the pictures you show on the television are all Caucasians, and that’s not true. In Revelations it says, “I heard a voice speak to me and I turned and looked and his hair was white like lamb’s wool, and his hands and feet like fine brass as though put into an oven, and his eyes were like a flame, and his voice was like the sound of many waters.” All right. There are only one people who have hair like lamb’s wool. And you’ll see often times people from Africa, the white part of their eyes is red like a flame. And, yes, the original Jews, Moses was not a Caucasian. Hanging on the cross, it’s a European. That’s just not true. They need to deal with truth.

When I was singing with the Ink Spots, the lead singer of the Ink Spots, Bernie Mackey and his fabulous Ink Spots, and we went to Europe NATO bases, Italy and Naples. So I figured while I’m in Naples I might as well go to Rome and check it out. Magnificent building. It’s just like I had heard, that Moses’s toes is eroding because so many people are kissing his feet. But it’s a white man. Well, there’s nothing in there—beautiful inside, but wasn’t telling the truth who the man Jesus was, ethnically. And that’s important. Religions should be dealing about truth. As I say, because of my singing and whatnot, going to Catholic Churches hanging on the cross they’ve got a big Caucasian man, that’s just not true. Mary was not a European, neither was Moses. You turn on the TV, they’re all Caucasians. That’s not true. It’s stealing other people’s history.

What is interesting as you—turn the globe around to you some. Keep on going, keep on going. Now stop. You heard about plate tectonics? You can see how South America fits right into Africa. And if you find Egypt, you can take a line and it will lead right over to Central America and you have pyramids there. And there’s the olmec heads. The Africans were here and there’s no doubts about—ever seen an olmec head?

Q: I have not.

Tshaka: No doubt who they were. Very powerful, strong African features. Yes, the Africans were here. I’m going to say they were here before the indigenous people came in from Asia, wherever they came in down this way. But there are pyramids in Central America and in South America. They’ve got pyramids over in Egypt. And, by the way, if you take a ribbon it goes right around into China, India, there’s pyramids.

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: Yes. But it’s about truth. You shall know the truth and the truth will set you free. They’re telling a story, but they don’t tell it all.

Q: Sounds like you have some more work to do.

Tshaka: Well—if it’s to be, it will be, you know. I hate to say, you know. If it’s to be, it will be. If I’m chosen to do, I’ll do it. But you see I can’t get around. Thank God I’ve got scooters and whatnot that I can scoot here and scoot there. But my cousin Connie, she’s always going on cruises or whatnot. [Laughs] If you want to go on a cruise there she is.

Q: [Laughing]

Tshaka: She took me on a cruise about four or five years ago, up the Atlantic ocean, and the ocean was carrying on. It was in the fall or winter here. I don’t want to see the Atlantic ocean no more. I remember I was at a breakfast and the ocean was kind of—the pots and pans were falling off in the cafeteria. I said, “Mr. Poseidon, if you just get me near the shore, I promise you I’ll never disturb you again.” I don’t want to see it. “Oh, well, I’ve got so much money to go on a cruise to the Caribbean.” Oh, no, they’re lovely looking boats but I don’t want to see it. She also took me in 1998 to Guyana and Benin. That was very educational, and that was wonderful. But Mr. Atlantic, I ain’t going to bother you.

Q: I’m with you on that.

Tshaka: No [laughs].

Q: So is there anything else you want to tell me before we say good-bye and turn the recorder off?

Tshaka: Well, I do hope that God will intercede about the burial ground because those people buried there, they’re entitled to that respect. I don’t care whose burial grounds they are. But if the City of New York can put up those, on city land, the memorials for the Jews who were slaughtered over in Europe, then why the hell can’t you put it over here? And at the north end of the burial ground there is—

[INTERRUPTION]

Q: So I wanted to ask you, how did you get John Liu to help you with the burial ground?

Tshaka: He was a councilman at that time, and his office was in Flushing, and I started going over there and he did. Nice man, John Liu.

Q: And I saw the Queens Borough President at the time, Helen Marshall.

Tshaka: Yes, yes, yes.

Q: She also—

Tshaka: Yes, very helpful.

Q: How did you get her to help?

Tshaka: Just brought it over to her, and it was under her administration that they opened up the site. There was a ceremony, and they had speakers. I remember I sang, and it was quite an event. The burial ground, along 165th Street—because it was country at the time, the burial ground when it was—not before 1935, but the burial ground extended over to where those houses are on 165th Street. You can see it. So they’re built on, and the street, too, is built on part of the burial ground. And at one time before they put in Rocky Hill Road, the burial ground it extended over to where Flushing Cemetery is. And I’m inclined to think that’s why people who look like this [points to himself] are there, because that was the colored cemetery of Flushing. Then when they put in Rocky Hill Road, it was pulled back and the remains that were there I want to say dumped over where the site is.

As I say, it was vicious. They didn’t have to do that because just around the corner, about four blocks away, is Kissena Park. Nothing but old devilish racism. You don’t go around disturbing—I don’t care whose remains they are. The word is last resting place, and that’s what it should be, and it should be treated with respect. Yes. What goes around comes around.

Did you see all this in the back up in here? That was given to me by the Community Board Number 11.

Q: For all the work that you did.

Tshaka: For different things I was doing. And there was clippings from newspapers.

Q: Fighting drug dealers, other crime. Good work. Good work.

Tshaka: Would have never thought that I would have done it, or that I have become the person that I am. But when I look back, and then they say you’ll understand it better by and by. I think that baby picture tells a lot. There I’m sitting just as bold—and my mother—that picture there was taken of her at Saranac Lake with tuberculosis.

Q: She’s so small and frail.

Tshaka: Mm-hmm. And my sister died right after I was born. Just absolutely amazing and I’m still here. And when I go down the street you can feel the atmosphere change. You can feel everything straightens up. It’s just amazing. Yes. But, anyway, this too shall pass.

The burial ground to the north on 165th Street, we compromised and gave them a little playground that they could play, put their little children in. That’s up to the north. That’s north. But the rest is not to be played with. And they have a tendency to neglect it. But if you go to Crocheron Park, manicured. Kissena Park, manicured. The World’s Fair, manicured, and on and on and on. Even in death, the people—the Town Hall in Flushing, I read that its built on a Matinecock burial ground. It’s really disturbing. But the average person doesn’t know. They don’t know about that.

And as I say in Macedonia, they’ve got human remains. They’re talking about building a brand new church. Are they out of their mind? In the Bayside Times, it talks about the borough president that they’re not going renovate it. That’s what needs to be done. And she stressed the point that it’s the third oldest religious institution in Flushing. You don’t tear those things down, renovate them. And they’re talking about putting in one of those apartment houses. I said, “Are you out of your mind.” Not only that the demographics—have you been in Flushing?

Q: I have.

Tshaka: I become speechless when I go down there. I never saw so many people. The Chinese, I’ve never seen—because as I say I can go way back—it wasn’t that way. I mean there are so many people there that you have to walk out in the street sometimes. It’s just amazing. The St. George’s Episcopal Church has an accommodation on it—the king or somebody did something for the church. It’s very old. The British. Mm-hmm.

Q: Sounds like your next fight is to save the church.

Tshaka: Well, you know, I personally can’t get down there. There is nowhere to put my scooter. And then I would want to have the problem like I just had. Part of the family, where I stayed in Flushing, Marjorie died recently. I wanted to sing but I didn’t want to go there and have to do this. And I couldn’t make it.

Q: Yeah.

Tshaka: This is true, I mean, I would like to you but I wouldn’t want to be in a compromising position.

Q: Of course.

Tshaka: And I can’t move. So that’s how it is.

Q: All right.

Tshaka: When I done the best I can and my friends don’t understand. He looked beyond my faults and saw my needs, and you’ll understand it better by and by.

[INTERRUPTION]

Tshaka: They put a plaque up in Bayside Historical Society honoring me. So it was quite a journey. Quite a journey.

Q: Shall we say good-bye?

Tshaka: Hmm?

Q: Shall we say good-bye? Shall we turn this off?

Tshaka: Sure.

Q: All right.

Tshaka: May the creator keep you safely in the palm of his hands.

[END OF INTERVIEW]