Berman v. Parker (1954)

The Berman v. Parker decision established the principle that aesthetics alone sufficiently justified government regulation of private property.

Appellees:

Appellant’s Claim:

Chief Lawyers for Appellants:

Chief Lawyer for Appellees:

Justices for the Court:

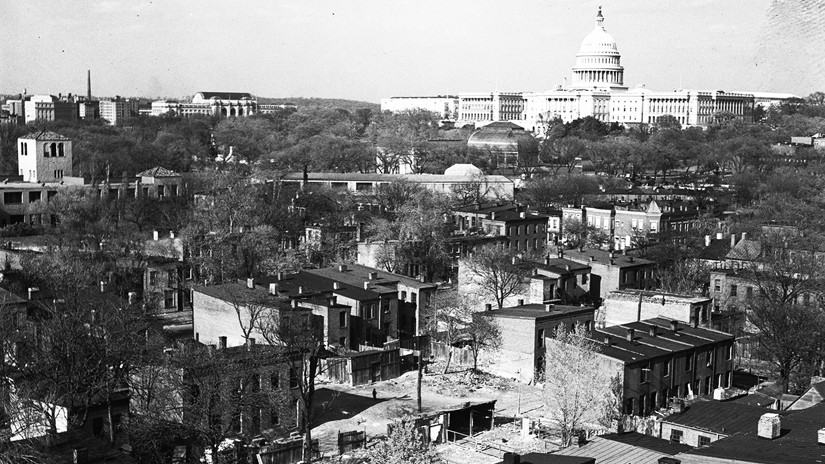

Berman v. Parker involved a slum clearance project in Washington, D.C. Berman, a local businessman, decided to fight against the taking of his property. He argued that though the redevelopment project had been authorized to eradicate “local blight,” this term did not include his thriving business, which was housed in a sound building, and in no way presented a hazard to the public well being. Consequently, Berman argued, in seizing his property, the government had been motivated by an aesthetic impulse, not recognized in the law.

The lower courts agreed with Berman, and ruled in his favor. The Supreme Court, however, found that “It is well within the power of the legislature to determine that the community should be beautiful as well as healthy, spacious as well as clean, well balanced as well as carefully patrolled,” and therefore, the government obtained the right to Berman’s property.

1954: The Berman v. Parker decision establishes the principle that aesthetics alone sufficiently justifies government regulation

February 1955: Albert S. Bard refers to the Berman v. Parker case in his article "Esthetics and the Police Power," which was published in American City

April 2, 1956: The Bard Act is passed into law and provides the legal basis necessary for the creation of landmarks legislation

The Berman v. Parker Decision (1954) established the principle that aesthetics alone sufficiently justified government regulation. Preservationists soon recognized that this precedent could be used to justify protective historic ordinances.1

The Berman v. Parker decision upheld the constitutionality of the District of Columbia’s Redevelopment Act. In so doing, the court affirmed the government’s right to acquire private property - in this particular case, a department store (located at 712 Fourteenth Street, S.W. Washington, D.C.) - as part of an effort to redevelop a blighted neighborhood.2

In Berman v. Parker the court ruled, "It is within the power of the legislature to determine that the community should be beautiful as well as healthy, spacious as well as clean, well balanced as well as carefully patrolled...If those who govern the District of Columbia decide that the nation’s capitol should be beautiful as well as sanitary, there is nothing in the Fifth Amendment that stands in the way."3 The wording of this decision affirmed that cities have a right to be beautiful, and thus granted legislative validity to the concept of aesthetic regulation, which preservationist Albert S. Bard had advocated for years prior to this decision.4

Albert S. Bard studied the court’s decision on this case and quickly realized its importance.5 During a 1954 Municipal Art Society board meeting, Bard noted that, "the decision emphasizes the right of community to regulate private property upon the basis of community beauty and appearance, regardless of the more usual factors of health, safety, morals and public convenience. The case is likely to become a leading case in the law of planning and on the controversial matter of public control of private property with respect to exterior appearance.”6

In February of 1955, Bard's "Esthetics and the Police Power," was published in American City. In the piece he included a long extract from the Berman v. Parker case, and demonstrated how Justice William O. Douglas's choice of words helped advance the case for aesthetic regulation proposed in a draft of the Bard Act.7

Berman v. Parker created a more favorable legislative environment for advancing the Bard Act, which proposed "To provide for places, buildings, structures, works of art and other objects having a special character, or special historical or aesthetic interest or value, special conditions or regulations for their protection, enhancement, perpetuation or use, which may include appropriate and reasonable control of the use or appearance of neighboring private property within public view, or both. In any such instance, such measures, if adopted in the exercise of the police power, shall be reasonable and appropriate to the purpose, or, if constituting a taking of private property, shall provide for due compensation, which may include the limitation or remission of taxes."8

The Bard Act was passed into law on April 2, 1956, and provided the legal basis necessary for the creation of landmarks legislation.9

- Municipal Art Society Board Meeting Minutes

Municipal Art Society of New York Records

Archives of American Art

1285 Avenue of the Americas, Lobby Level

New York, NY 10019

Tel: (212) 399-5015

Fax: (212) 307-4501

- Oral Histories with Frank Gilbert and Leonard Koerner

New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Tel: (212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org