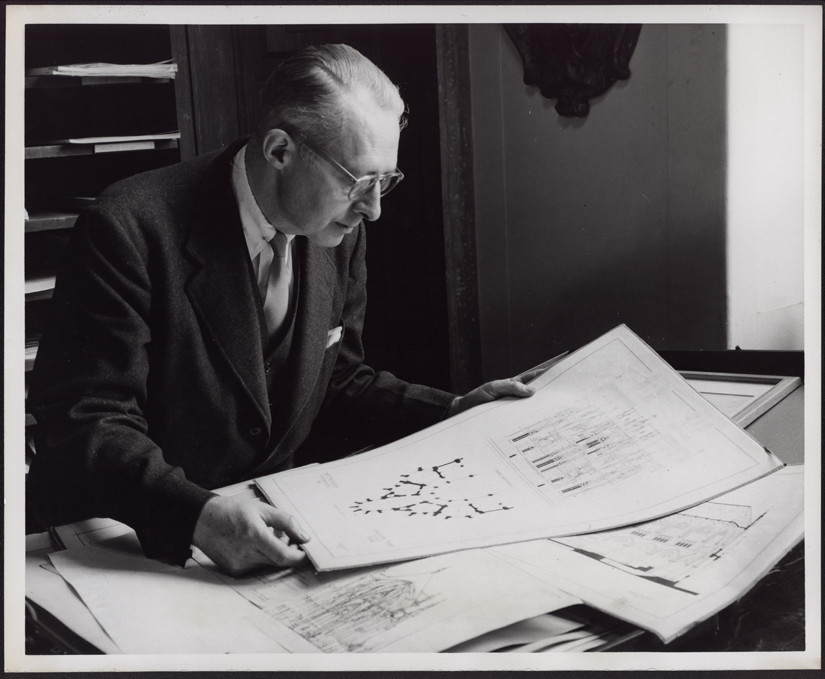

James Grote Van Derpool

Also known as James Van Derpool

James Grote Van Derpool’s research and directorship of the Landmarks Preservation Commission led to the designation of New York City’s first official landmarks.

James Grote Van Derpool was born in 1903 into one of New York’s earliest founding families.1 He received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1927 and conducted graduate research in architectural history in 1928 and 1929 at the American Academy in Rome and the Atelier Gromort of the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.2 Upon his return from Europe, Van Derpool served as an architectural history instructor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York after which he received a Master of Fine Arts in Architecture from Harvard University in 1940. Later, he became the Director of the Art Department at the University of Illinois. In 1946 he succeeded Talbot F. Hamlin as the principal librarian at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University where he greatly expanded its holdings. Ada Louise Huxtable, in recounting Van Derpool’s term at Avery, described him as “a man of impeccable credentials and connoisseurship.”3 From 1959-1961, he was acting and then Associate Dean of the Columbia School of Architecture.4

During his tenure at Columbia, he was very active in various university committees, boards and organizations. He served as a Trustee of Columbia University Press from 1959 to 1962; committee member of the College Advisory Board for the School of Painting and Sculpture from 1959 to 1961; as well as the project for the “Future of Columbia University” from 1959 to 1960 and committee chair for the selection of the Dean of the School of Architecture from 1959 to 1960.5

The reach of Van Derpool’s work extended far beyond the university campus. He was a highly respected professional, nationally recognized as an expert in the fields of architectural history and preservation.6 As the executive director of the newly formed New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission from 1961-1966, Van Derpool led the nascent agency in its organizational and day-to-day work. Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. later praised him for his “administrative ability, scholarship and dedication to the cause of preservation.”7 He was quoted regularly in The New York Times as well as many other publications, as the spokesperson for the commission’s positions.8 He was a scholar of international acclaim and a voice of authority for New York’s, and the country’s, architectural heritage.9

James Grote Van Derpool’s efforts provided the intellectual groundwork for the New York City Landmarks Law. His research and executive direction over the Landmarks Preservation Commission led to the designation of New York City’s first official landmarks. In 1965, Van Derpool was the recipient of the George McAneny Historic Preservation Medal for his contribution toward the preservation of architecturally and historically significant buildings in New York.10 That same year he was named Benjamin Franklin Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in London.11

Van Derpool retired to his home in Esopus, New York in 1966, just months after the Landmarks Law was signed. He died in 1979.

Trustee, American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1945-1965

President, New York and National Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians, 1951-1957

Chairman, Advisory Committee: Historic American Building Survey, National Park Service, 1956-1962

Executive Director, Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1961-1965

Chairman, Design and Construction Committee: Committee for Gracie Mansion, 1965

James Grote Van Derpool was involved in the development of the publication New York Landmarks: An Index of Architecturally Historic Structures in New York City. As president of the New York Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Van Derpool partnered with Edward Steese of the Municipal Art Society in 1951 to assemble a comprehensive list of New York City's architecturally and historically significant structures, called New York Landmarks: An Index of Architecturally Historic Structures in New York City that expanded upon Talbot F. Hamlin's 1942 Tentative List of Old Buildings of Manhattan Built in 1865 or Earlier, and Worthy of Preservation, Annotated by Talbot F. Hamlin. Steese and Van Derpool developed a questionnaire that was circulated among their members as well as libraries, historical societies, architectural firms, and other interested parties to research and update the preliminary list. This compilation was one of the first of its kind that provided a scholarly foundation for the burgeoning New York preservation movement.12 The result was an ever-expanding index that underwent many subsequent editions, resulting in Alan Burnham's 1963 New York Landmarks; a Study and Index of Architecturally Notable Structures in Greater New York, published under the Municipal Art Society and described by Brendan Gill as a "veritable Kama Sutra" for devotees of New York.13

Van Derpool was also heavily involved with the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Van Derpool was sworn in as the executive director of the newly formed Landmarks Preservation Commission on May 21, 1962. When he was approached by Geoffrey Platt about finding an executive director of the nascent commission, Van Derpool offered to fill the position himself, saying "This has been my dream my whole life.”14 Under his direction, the Landmarks Preservation Commission was responsible for the designation of buildings, monuments, and other works of aesthetic or historic importance for preservation. The commission was responsible for receiving questions on specific preservation cases from the City Planning Commission, the Housing and Redevelopment Board, the New York City Housing Authority, and any other city agencies involved, and recommend appropriate action. Lastly, the commission was responsible for the submission of a detailed legislation program that effectively protected those portions of designated landmarks that fell within public view.15

As the salaried member of the agency, Van Derpool was responsible for hiring and overseeing a research staff that surveyed the architectural remains of the City's five boroughs to recommend any sites worthy of landmark status.16 In selecting landmarks, the Landmarks Preservation Commission sought to highlight representative examples that would illustrate the City's growth from Dutch trading settlement to international metropolis.17 Before his retirement at the end of 1965, the Landmarks Preservation Commission had designated 38 landmarks for the City of New York.18

In addition, Van Derpool was involved with the preservation of the Pyne-Davidson Block Row, located on Park Avenue between 68th and 69th Streets. Cited by Van Derpool as "one of the finest residential block-fronts of the period in the entire country," the block featured four architecturally coherent townhouses with two designed by McKim, Mead & White (1909, 1926); one by Delano & Aldrich (1918); and another by Walker & Gilette (1917); all with a continuous facade. In 1964, three-quarters of the block was sold to a real-estate developer who planned to raze the properties to make way for a 31-story apartment building.19 Lacking the legislation to legally prevent demolition (a draft was still under scrutiny by City agencies), the Landmarks Preservation Commission sought salvation through their own network.20

With great foresight, Van Derpool persuaded the owners of the buildings to take a lower price for a one-year grace period so that possible methods of preservation could be pursued. He then enlisted the help of real estate entrepreneur Peter Grimm, who arranged for a last-minute sale to the Marquesa de Cuevas (formerly Margaret Rockefeller Strong) who, in turn, donated them to the City for cultural use.21 This case marked the first sale of a New York building of particular historic and architectural value in which the judgment of the Landmarks Preservation Commission played a significant role.22 The whole operation was, in effect, the first unofficial demonstration of the protection that the Landmarks Law would eventually provide.

Furthermore, Van Derpool was involved with the effort to preserve the Brokaw Mansion. The demolition of the Brokaw Mansion, which began in early 1965, played a significant role in advancing legislation for a Landmarks Law. The Landmarks Preservation Commission had unofficially designated the Brokaw Mansion as a city landmark, equipped with a plaque, yet they were without any legal right to prevent the plans for demolition announced in September 1964. Despite this, members of the Landmarks Preservation Commission and other concerned groups such as the Municipal Art Society and the Architectural League, sprang to action, resulting in a slew of editorials protesting the impending demolition as well as a letter to Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. urging the advancement of the Landmarks Law. In addition, considerable oppositional fervor from the public arose. As the veritable spokesman for the Landmark Preservation Commission, Van Derpool deplored the razing of the mansion as the:

"loss of still another example of New York in the Age of Elegance precisely at a time when new interest and understanding of that period is so strongly present."

He went on to say that "architecture throws light on history," and then added, "we need such structures in order to understand in a meaningful way how people lived at a time very different from our own.”23 However, this was all to no avail. Despite the commission's desperate actions, the Brokaw Mansion was replaced by a 26-story apartment building in 1966.

Van Derpool was also involved with the effort to preserve the Old Merchant's House (also known as the Seabury Tredwell House). Built in 1832, the Greek Revival exterior, interior, and furnishings of the Old Merchant's House remained in very much its original state since its construction. Van Derpool called the house "a document of great importance for its authenticity.”24 In 1965, threatened with sale and demolition, along with dispersal of its contents, the Old Merchant's House was in a badly deteriorated state due to steep maintenance and repair costs. Operated since 1939 as a house museum by the privately organized, state-chartered Historic Landmark Society, attempts to obtain financing from private contributors proved unsuccessful.25 That spring, a developer bought the two adjoining lots with the intention of constructing a parking garage and it was made clear to the public that the Old Merchant's House was threatened. The Landmarks Preservation Commission had preliminarily selected the house for landmark status yet, as of April 1, 1965, the bill had yet to be voted on by the city council and the commission was officially unable to prohibit or stall the building's demolition.26

Van Derpool and the commission took unofficial action. They organized a passionate public outcry through the press, prominent individuals, and numerous organizations. In one instance, Van Derpool, along with Senator Frederick S. Berman, met a group of student protesters, armed with petitions bearing thousands of signatures destined for City Hall, on the steps of the Old Merchant's House, which spawned a huge amount of media attention.27 Public pressure mounted and the City Council approved the landmarks bill on April 6, 1965. Mayor Wagner signed the bill into law on April 19, 1965. The exterior of the Merchant's House was officially designated a landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission on October 14, 1965 and is to this day one of New York's most treasured landmarks.

Finally, Van Derpool also offered his expertise to the construction of a new wing onto Gracie Mansion. Van Derpool served as Chairman of the Design and Construction Committee that supervised the planning and construction of the 1965 addition to the mayor's official residence, Gracie Mansion (built in 1798). The new wing was noted for "its scholarly and appropriate good taste.”28 The Landmarks Preservation Commission officially designated the site as a landmark in 1966.

- The James Grote Van Derpool Papers

Department of Drawings & Archives

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Columbia University

1172 Amsterdam Avenue

New York, NY 10027

Tel: (212) 854-4110

Email: avery-drawings@cul.libraries.columbia.edu - Anthony C. Wood Archives

The New York Preservation Archive Project

174 East 80th Street - New York, NY 10075

Tel: (212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org - Century Association Archives Foundation

7 West 43rd Street New York, NY 10036

Email: archives@thecentury.org - Oral History with Frank Gilbert, Otis Pratt Pearsall, Adolf Placzek, and Geoffrey Platt

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- ”Obituary 9″, The New York Times, 24 September 1979.

- Ibid.

- Ada Louis Huxtable, “A Place of Genuine Joy,” The New York Times, 2 April, 1972.

- “James Grote Van Derpool papers, 1944-1974 (bulk 1962-1966): History / Biographical Note,” Columbia University Libraries: Archival Collections: Avery Drawings & Archives Collections. Article retrieved 12 March 2016

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Director of Landmarks Quits on Advice of Physician,” The New York Times, 24 November 1965.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 289.

- Charles G. Bennett, “City Asks to Save Landmarks; Names Scholar to New Agency,” The New York Times, 1 July 1962.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Director of Landmarks Quits on Advice of Physician,” The New York Times, 24 November 1965.

- James Grote Van Derpool papers, 1944-1974, Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- Anthony C. Wood, The Past Is Never Dead. It is Not Even Past, Keynote Address for “Preserving New York Then and Now Symposium,” The Museum of the City of New York, 28 February 2008.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 326.

- Ibid., page 289.

- Ibid., page 304.

- James Grote Van Derpool papers, 1944-1974, Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Landmarks Commission Seeks to Preserve Splendor of City’s Past,” The New York Times, 21 July 1963.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission Designation Reports, 1965.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Marquesa Saved 2 Landmarks,” The New York Times, 14 January 1965.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), pages, 344 – 347.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Marquesa Saved 2 Landmarks,” The New York Times, 14 January 1965.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Low Bid Gets Park Avenue Home on Promise Not to Rip It Down,” The New York Times, 28 February 1964.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Landmark Mansion on 79th St. to be Razed,” The New York Times, 17 September 1964.

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “1832 ‘Village’ Landmark Faces Demolition,” The New York Times, 18 February 1965.

- Ibid.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), pages 356-360.

- Ibid.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Gracie Mansion Getting an 18th-century-style Wing,” The New York Times, 12 January 1965.