Lenore Norman

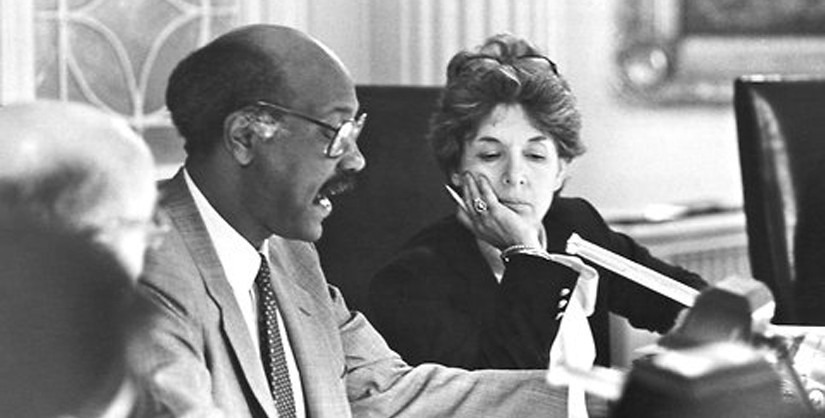

Lenore Norman was executive director of the Landmarks Preservation Commission from 1974-1985, a time of great growth, transition, and legal battles at the agency.

Lenore Norman was born in New York City in 1929 and was raised in the Upper Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights. She was a graduate of Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, where she majored in sociology. After college, she returned to New York City, where she married Milton Norman in 1951. She spent much of the next two decades raising her two children, while also becoming involved in civic activities. Eventually, she began taking courses at the New School and developed an interest in urban planning.1

In the early 1970s, she interned at the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) while pursuing a graduate degree in urban planning at Pratt Institute. She then became an assistant to LPC Executive Director Alfred Shapiro, who served for only one year.2 After Shapiro’s departure Norman was named executive director, a role she held until 1985.3

Lenore Norman was executive director during the tenures of three LPC Chairs with very different approaches to the position. She began working under Beverly Moss Spatt, who was named chair in 1974 and had previously been a City Planning Commissioner. In 1978 Kent Barwick became chair, ushering in a comparatively aggressive approach to preservation.4 The last two years of Lenore Norman’s tenure at the Commission were spent under the chairmanship of Gene A. Norman (no relation to Ms. Norman).5

After leaving the Commission, Norman took a position at the New York City Department of Buildings, where she handled intergovernmental relations. Later, she sold residential real estate and served as the co-chair of the Landmarks Committee of Community Board 7 on the Upper West Side, a position she held until 2012. Lenore Norman died on December 21, 2012.

Landmarks Committee of Manhattan's Community Board 7

Co-Chair

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

Executive Director,

Norman was executive director during a time of transition at the LPC. The Commission’s first two chairs–Geoffrey Platt and Harmon Goldstone–had both been active at the Municipal Art Society when that organization was advocating for and helping shape the legislation that would ultimately create the LPC. Beverly Moss Spatt, Goldstone's successor in 1974, had a different background. A former member of the City Planning Commission who had disagreed with Mayor Lindsay's high-rise development plans, Spatt prided herself on upholding what she called “standards and equity” at the LPC and once told the The New York Times that she “made a government agency out of what used to be a tea party.”6 Spatt brought in Norman–an urban planner by training–to administer the Commission during this transitional period.

In 1978, newly elected Mayor Ed Koch replaced Spatt with Kent Barwick, a prominent preservationist who had been executive director of the Municipal Art Society. Barwick led the Commission during a time of significant growth and legal challenges. Norman continued as the Commission’s director, a testament to her skill in managing the growing City agency while upholding the professionalism of LPC staff through contentious preservation battles. Norman’s public role was muted; she was infrequently quoted in the press. Instead, she concerned herself with the Commission’s day-to-day operations as it managed an increase in the volume of designations and regulated alteration proposals for a rising number of landmarks. The booming real estate market of the 1980s led to substantial increases in the Commission’s workload. In 1980, the LPC had 32 employees and reviewed 735 applications for alterations; by 1984, it had 42 employees, reviewed 1,753 applications for alterations, and was planning to increase its staffing further to cope with the growth.7 Norman is remembered for her careful attention to the concerns of both preservationists and applicants during this time of expansion.8

During Norman’s time of service, important verdicts were made that helped secure the Landmarks Law’s constitutionality. Most prominent was the legal battle surrounding Grand Central Terminal, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, which resulted in the 1978 United States Supreme Court decision to uphold the law. Another significant case was that involving St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, which sought in the early 1980s to demolish its landmark-designated community house to make way for a speculative 59-story commercial structure adjacent to the main church building. In 1984 the Commission rejected this proposal, which ultimately led to a 1990 federal court decision affirming that the Landmarks Law did not violate the church’s constitutional rights and rejecting the assertion that religious structures should be excluded from historic ordinances.9

In all, roughly 350 individual landmarks and historic districts were designated during Lenore Norman’s career at the LPC. Among the many notable designation milestones reached during Norman’s tenure include the 1979 designation of the New Amsterdam Theatre; the 1982 designation of Lever House, which was upheld by the Board of Estimate in a close vote; the 1983 designation of the Woolworth Building; the designation in 1977 of the South Street Seaport Historic District; the 1981 designation of the Upper East Side Historic District, among the city’s largest; and the designation of historic districts in several Brooklyn neighborhoods including Greenpoint, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and Prospect-Lefferts Gardens.10

- Oral History with Lenore Norman

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Milton Norman, personal communication, 13 February 2013; David Dunlap, “Lenore Norman, a Quiet Force for Landmarks Preservation, Dies at 83,” The New York Times City Room Blog, 27 December 2012.

- Ben Baccash, “Frank Gilbert Oral History Interview,” New York Preservation Archive Project, March 2011; Marios Drakos, “Lenore Norman: An Oral History Interview,” New York Preservation Archive Project, 15 October 2008.

- Michael Oreskes, “On 20th Anniversary, Landmarks Panel Is Strong but Controversial Force in City,” The New York Times, 24 April 1985; Jane Gross, “Landmarks Panel Staff Urges Rejection of East Side Tower,” The New York Times, 9 October 1985.

- Edward Ranzal, “Barwick Given Mrs. Spatt’s Landmarks Job,” The New York Times, 3 March 1978.

- David W. Dunlap, “New Landmarks Chief: Gene Alfred Norman,” The New York Times, 29 June 1983.

- Ronald Smothers, “Critic Loses Her Position On City Landmarks Unit,” The New York Times, 24 August 1982.

- Michael Oreskes, “On 20th Anniversary, Landmarks Panel Is Strong but Controversial Force in City,” The New York Times, 24 April 1985; A.O. Sulzberger, “Landmarks Panel Adopts Bolder Tack,” The New York Times, 20 September 1981; City of New York, The Mayor’s Management Report, September 1981; City of New York, The Mayor’s Management Report, September 1985.

- David W. Dunlap, “Lenore Norman, a Quiet Force for Landmarks Preservation, Dies at 83,” The New York Times City Room Blog, 27 December 2012.

- David W. Dunlap, “Landmarks Panel Vetoes Tower Plans for St. Bart’s and Historical Society,” The New York Times, 13 June 1984; David W. Dunlap, “Church’s Landmark Status Is Upheld,” The New York Times, 13 September 1990.

- Matthew A. Postal, ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks, 4th ed. (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009); David W. Dunlap, “Board Sustains Lever Building As a Landmark: Citation of Office Tower Survives Repeal Effort,” The New York Times, 19 March 1983.