Robert F. Wagner, Jr.

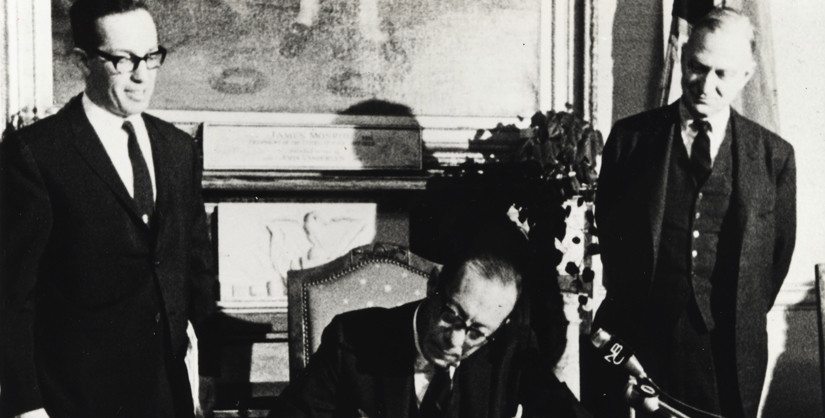

Former New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner signed the New York City Landmarks Law and established the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Robert Wagner was considered New York’s “first modern mayor” by former Mayor John Lindsey.1 The son of former New York Senator Robert Wagner, Sr., politics came naturally to his stature.2 His father was deeply influenced by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal and was the author of the “Wagner Act,” which created the National Labor Creation’s Board.3

Robert Wagner was born on April 20, 1910 in the Yorkville area of Manhattan. He attended both Loyola School on Park Avenue and Taft School in Connecticut. In 1933 he completed his bachelor’s degree at Yale University. Subsequently, he attended Harvard Business School and the School of International Studies in Geneva. He received a law degree from Yale in 1937. During World War II, he served in the Air Corps as an intelligence officer.4

After the war, Wagner steadfastly joined the political realm when he was appointed by then Mayor O’Dwyer as City Tax Commissioner. In addition, he was appointed as the Commissioner of Housing and Buildings and Chairman of the City Planning Commission. In 1949, he was elected Manhattan Borough President. Wagner also served as chairman of the City Planning Commission. However, he is most noted for his service as mayor of New York City. He was elected as mayor in 1953 and continued to serve for three consecutive terms. During the 1957 mayoral race, he secured 920,000 votes, a feat never matched prior to this election.5

Robert Wagner served as mayor during massive urban development due to the post-war economic boom and “white flight” suburban expansion. He was responsible for securing funds from both the state and federal government for massive slum clearance projects and urban renewal public housing. During this time, New York City experienced a massive wave of migration of African Americans from the south, and Hispanics from the Caribbean and Puerto Rico. He is known for integrating the City government by appointing both African American and Hispanic officials.6

Of other significance: he established Shakespeare in Central Park, the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadow, the Lincoln Center for Performing Arts, and the Gateway National Park. While he lost the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, he gained the Mets in a new stadium in Queens.

His legacy as mayor of New York in hindsight is equivocal. While he helped facilitate the passage of the New York City Landmarks Law by signing the legislation and helped aid in saving historic structures including Carnegie Hall, he was also responsible for the slum clearance projects that destroyed some of New York’s most precious jewels.

In 1968, he was appointed as the American Ambassador to Spain.7 Wagner spent the latter part of his life practicing law and offering his legal and political guidance to political officials in Albany and Washington, D.C. Robert Wagner passed away on February 12, 1991. He was 80 years old.

City Tax Commissioner

Commissioner of Housing and Buildings

Chairman, New York City Planning Commission

Manhattan Borough President, 1949

Mayor of New York City, 1953-1965

Robert Wagner's contribution to the preservation movement in New York City was complex. While he signed key legislative measures that created the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, he was also responsible for slum clearance of "blighted areas" for urban renewal projects. Nevertheless, he saved several of New York's architectural gems from demolition. Often caught between the interests of the real estate community and the interests of preservationists, it was under his administration that the New York City Landmarks Law came to fruition.

Mayor Wagner was first involved in the effort to preserve Carnegie Hall. On January 5, 1960, Robert E. Simon, Jr., owner of Carnegie Hall, had announced plans for its demolition. Preservationists worked diligently to save the building by forming a not-for-profit organization to subsume ownership in order to preserve the building. However, the organization was impeded by not having the legislative means to take over the property. Senator MacNeil Mitchell drafted legislation to allow municipalities to "acquire by condemnation any property 'with special historical or esthetic interest or value.’”8 A second bill was introduced to allow for the creation of the not-for-profit group Carnegie Hall Corporation to lease the hall from the City until it could amortize the price of the building.9 On June 30, 1960, Mayor Wagner announced that the City of New York had acquired Carnegie Hall and would lease the property to Carnegie Hall Corporation. At the grand reopening of Carnegie Hall, Mayor Wagner, a proponent for preserving the concert hall, charismatically conducted the orchestra at the celebratory event.10

Robert Wagner also played a significant role in the preservation of the Jefferson Market Courthouse. As early as 1950, after sitting vacant for five years, the City planned to demolish the courthouse. Nearby Greenwich Village activists rallied around preserving the courthouse and adaptively reusing the structure as a library but were impeded due to lack of funding for its renovation. In August of 1961, Mayor Wagner spoke in favor of its preservation. He facilitated the renovation by allocating City funds for the New York Public Library to take over the courthouse.11

In addition, prior to his appointment as Manhattan Borough President, Robert F. Wagner, Jr. served as chairman of the City Planning Commission in 1948. During his time as chairman he was interested in the role of the Municipal Art Society in community development.12 After becoming mayor, he appointed James Felt, former governor of the Real Estate Board of New York, as chairman of the City Planning Commission. Mayor Wagner was confident that James Felt would have the power and influence to change the outdated 1916 Zoning Resolution.13 Felt would also have a pivotal role in securing the passage of the New York City Landmarks Law because of his ties to the real estate community. Wagner and Felt's close relationship helped ease fundamental changes imposed by the 1961 Zoning Resolution that had been previously thwarted.14 Although some of the proposed aesthetic ordinances did not make it into the resolution, the new zoning limited building heights and setbacks, which helped retain historic neighborhood character.

Furthermore, Mayor Wagner helped to create the Committee for the Preservation of Structures of Historic and Esthetic Importance (a precursor to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, or LPC). On June 19, 1961, Mayor Wagner announced the creation of a mayoral study committee to review New York City landmarks worthy of protection. The committee's goal was to draft legislation that would protect potential historic landmarks. Mayor Wagner appointed 13 members to the Commission, with Geoffrey Platt as its chairman.15 The commission was comprised of an architect, lawyer, planner, realtor, and banker, and was to work in conjunction with the Municipal Art Society and the Fine Arts Federation in order to draft legislation to protect historic structures.16 The study committee would eventually become the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

On another note, Mayor Wagner announced September 28-October 4, 1964 to be "American Landmarks Preservation Week in New York City." This program was sponsored internationally by UNESCO and nationally by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Wagner's proclamation of Preservation Week was ironic due to the impending demolition of the Brokaw Mansion and the fact that the Landmarks Law had sat unsigned for weeks on Wagner's desk.17 While the Municipal Art Society, American Institute of Architects, the Architectural League, and the Fine Arts Federation commended Wagner for this proclamation, it spurred a more pressing concern for the impending passage of the Landmarks Law as expressed in an urgent telegram to the mayor.18

Despite this delay, after a long period of anticipation, Mayor Wagner finally signed the New York City Landmarks Law on April 19, 1965. Although preservationists were relieved by the passage of the law, Wagner remarked that if property owners felt the law was too restrictive, provisions could be made in the future by the City Council to amend it.19 Despite these precautionary remarks, Wagner reflected later on in life that "creating the Landmarks Commission was probably the best thing that I ever did while I was the Mayor."20 In terms of historic preservation, he stated that “It was the most lasting contribution from my administration.”21

- Mayor Robert Wagner Archives

Fiorello H. LaGuardia Community College

City University of New York

31-10 Thomson Avenue, Room E238

Long Island City, NY 11101-3007 - Oral Histories with Seymour Boyers, Margot Gayle, Frank Gilbert, Robert Low, Whitney North Seymour Jr.,

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- James F. Clarity, “Robert Wagner, 80, Pivotal New York Mayor, Dies,” The New York Times, 13 February 1991.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Staff, “Wagner Sworn as Envoy,” The New York Times, 27 June 1968.

- Staff, “Saving Carnegie Hall,” The New York Times, 21 March 1960.

- Staff, “Saving of Carnegie Hall Enabled In Bills Signed by Rockefeller,” The New York Times, 17 April 1960.

- Allen Hughs, “Reborn Carnegie Makes its Debut,” The New York Times, 27 September 1960.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (Routledge: New York 2008), page 262.

- Gregory F. Gilmartin, Shaping the City: New York and the Municipal Art Society (Clarkson Potter Publishers: New York 1995), page 348.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (Routledge: New York 2008), page 230.

- Ibid, page 230.

- Staff, “Mayor Appoints 13 To Help Preserve Historic Buildings,” The New York Times, 12 July 1961.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (Routledge: New York 2008), page 270.

- Staff, “Anything Left to Preserve?” The New York Times, 24 September 1964.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (Routledge: New York 2008), page 333.

- Thomas W. Ennis, “Landmarks Bill Signed by Mayor,” The New York Times, 20 April 1965.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (Routledge: New York 2008), pages 361-2.

- Ibid, page 362.