Warburg Mansion

Also known as the Felix Warburg Mansion, Felix M. Warburg House, now part of the Jewish Museum

The Warburg Mansion is a case study in architectural adaptation and assimilation in the battle to bring a Gilded Age mansion into modern museum usage.

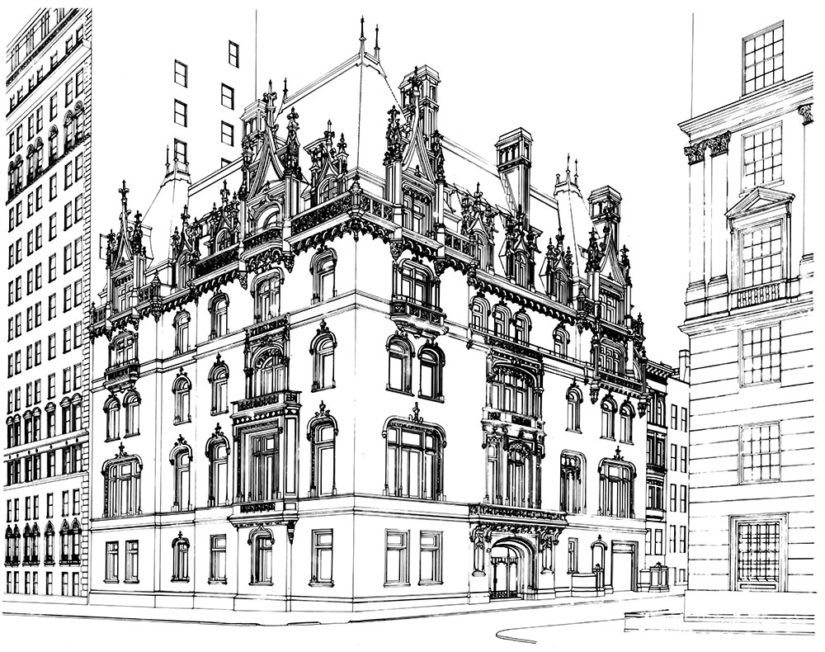

The Warburg Mansion was built in 1907-08 by the architect Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert (often referred to as C. P. H. Gilbert) for Felix M. Warburg, a prominent Jewish financier and philanthropist. On a plot of land across from the Central Park Reservoir at 92nd Street and Fifth Avenue, at the northern end of “Millionaires’ Row,” Gilbert constructed a Late Gothic/Early Renaissance Revival mansion. The Warburg Mansion was one of the numerous opulent Gilded Age mansions that were built in a range of architectural styles along Fifth Avenue, but it is significant today not only for its history and design but also for its survival where many of the other residences have been lost to demolition.

C. P. H. Gilbert, an architect known for using diverse styles when designing commissions for his wealthy clients, utilized for the Warburg Mansion the so-called François I mode, introduced by Richard Morris Hunt in the 1880s. This style was “adapted from the transitional Late Gothic and Early Renaissance styles of the Loire Valley.” Yet Gilbert’s design favors the Gothic details to those of the Renaissance, and in a bolder scaling.1 Much of the exterior was left as relatively simple expanses of Indiana limestone, with the majority of the ornament concentrated on the upper part of the house. The choice of the Gothic style, closely linked to ostentatious church architecture, led Warburg’s father-in-law Jacob H. Schiff to criticize the house, concerned that it would incite anti-Semitism.2

The mansion contained more than fifty rooms, many with rich detailing and wood paneling. Having grown up in these lavish surroundings, Edward Warburg would later recall that “father used to say had he had any idea what kind of family he was going to have, he never would have built a house as formal as this.”3 The ground floor contained a grand stairway, rooms for the family’s art collections, and spaces for philanthropic, social, and business meetings. On the second floor were the formal spaces of the conservatory, dining room, and a music room with a built-in organ. The third floor contained the more intimate spaces of the sitting room, breakfast room, and parents’ quarters, with the children’s quarters on the fourth floor. On the fifth floor Warburg had his squash court, and the sixth floor housed the servants’ quarters.

Warburg occupied the house with his wife Frieda and five children until his death in 1937, after which the family moved out. By 1941, after Frieda’s attempts to donate the house to a museum failed, news reports stated that the house would be demolished to make room for an 18-story apartment building designed by Emery Roth.4 However, by 1944 Frieda successfully transferred ownership of the mansion to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America for use as a museum, which opened in 1947 as the Jewish Museum.5

“The Felix M. Warburg mansion, one of the finest representatives of its style and of its era surviving in New York, is an eloquent reminder of the initial development of Fifth Avenue as a street of grand mansions and town houses, a testimony to the architectural elegance of an entire age as well as to the talents of an individual architect. Moreover, its current use as the Jewish Museum is a fitting tribute to the original owner and his family – to their beliefs, ideals, and traditions…The mansion itself is a tangible reminder of one facet of Jewish life in American history, and as such is one of the museum’s more important treasures.”6

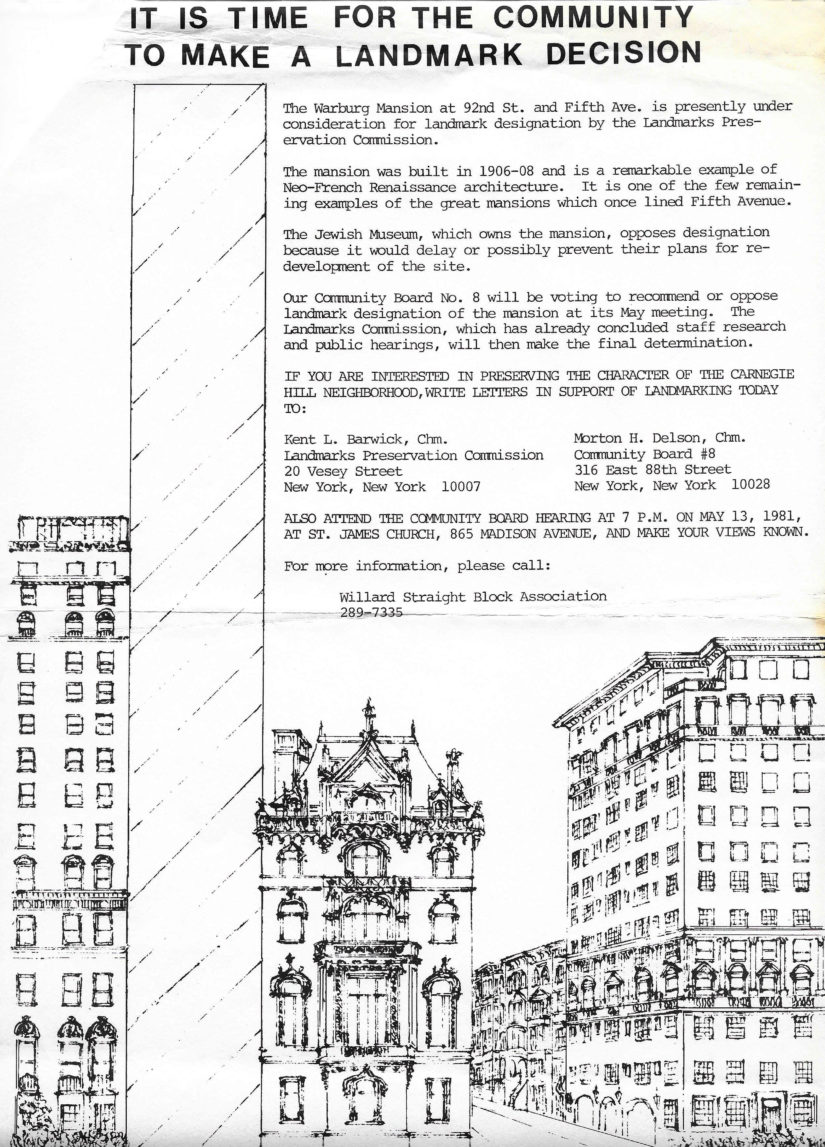

The Warburg Mansion has housed the Jewish Museum since 1947. In 1981 the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated landmark status on the mansion.

1980: Landmark designation of the Warburg Mansion is brought up at a LPC hearing but the Jewish Museum requests to defer action

1981: Plans are revealed to construct a residential tower next to the mansion; neighborhood action, led by Genie Rice at the Willard Straight Block Association, gathers over 900 signatures on a petition against the tower

November 1981: The Warburg Mansion is designated a New York City Landmark

1982: Alliance to Preserve the Warburg Mansion brings together seven block associations and over 70 individuals to collect more than 4,000 signatures against the construction of a tower

April 1982: The Board of Estimate upholds the building's landmark status, but in a compromise allows a modified construction plan for a tower

1988: New construction plan for museum addition scraps plans for tower and opts to expand with Kevin Roche’s seven-story design using the mansion’s Gothic Revival style

Major changes to the mansion began in 1962 with the construction of the List Building on an adjoining lot on Fifth Avenue, providing much-needed space for the museum. The three-story building, with its modern design by Samuel Glazer, shifted the entrance from the original impressive 92nd Street entry to one on Fifth Avenue.7

Less than a decade later in 1970, the Jewish Museum successfully opposed landmark designation by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), not wishing to limit their ability to fully utilize the property.8 But in 1980 landmark designation came up again at a LPC hearing, and the Jewish Museum requested to defer action.9 The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, the owner of the property, opposed landmark status for the building as it would impede with their plan to construct a residential tower in the place of the List Building. By April 1981 neighbors began to organize against the development of the proposed tower, which would alter the character of the neighborhood; the Willard Straight Block Association appointed Genie Rice as its representative in the campaign to secure landmark status for the mansion. Despite the success of “Dear Neighbor” letters that brought in more than 900 signatures as well as attendance at Community Board meetings, the Board voted against recommending landmark status in June.10

In November, as the LPC voted to designate the Warburg Mansion a New York City landmark, the Jewish Museum presented architectural plans for a 25-story tower attached to and cantilevering over the mansion, citing the need for the funds which the luxury apartment tower would generate for the museum.11 In anticipation of the Board of Estimate meeting which would approve or disapprove landmark designation, a coalition was formed, consisting of the Willard Straight Block Association, Carnegie Hill Neighbors, and Unity of 92nd Street, which petitioned Mayor Ed Koch and Borough President Andrew Stein with more than 1,200 signatures from the community.12 By February 1982 a larger coalition, the Alliance to Preserve the Warburg Mansion, came together, consisting of seven block associations and 73 individuals, with Rice appointed as coordinator. Their concern was not only the effect of the proposed tower on the fabric of the neighborhood, but also the landmark designation of the mansion, the validity of the New York City Landmarks Law, and the strength of the LPC. While the meeting with the Board of Estimate was laid over at the request of the Jewish Museum, the Alliance gained support in speakers and in signatures, with over 4,000 signatures by late March.13 This activity of the Alliance would eventually lead to the relaunch of CIVITAS, a new community organization to preserve and promote Manhattan's Upper East Side and East Harlem, under the leadership of Rice, August Heckscher, and Frank Lichtensteiger.14 With a final meeting on April 1, the Board of Estimate voted unanimously to uphold the landmark designation, but with a compromise that allowed for a smaller-scaled tower, 19 stories instead of the original 25, and narrower so as to not cantilever over the mansion.15

Despite this compromise, by 1988 the Jewish Museum had altered their construction plans again, this time towards something more community-minded and more likely to be agreeable to the neighborhood. Rather than a post-modern residential tower, an addition to the museum was proposed that would continue the late Gothic Revival style limestone façade across the Fifth Avenue lot where the List Building had stood. The seven-story design of Kevin Roche, of the firm Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo & Associates, differed from his other modern projects such as the Ford Foundation Building or his renovations to galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The plans, which gutted much of the interior including the grand oak stairway, doubled and modernized the museum space, and brought the entrance back to the grand 92nd Street entry. With a seamless exterior look, the design was met with support by the surrounding community.16 In 1993 the Jewish Museum reopened with the Roche addition complete, masterfully crafted by the Cathedral Stoneworks team from the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in limestone from the same quarry C. P. H. Gilbert used.17 With this expansion the museum became the largest Jewish Museum in the world outside of Israel.18

The Warburg Mansion landmark designation process “demonstrated that citizens can have power if they are organized and committed and persistent.”19 –Genie Rice

- Oral Histories with Laurie Beckelman and Genie Rice

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Oral History with Edward M. M. Warburg

- The New York Public Library, Dorot Jewish Division

- Stephen A. Schwarzman Building

- 476 Fifth Avenue (42nd Street and Fifth Ave)

- First Floor, Room 111

- New York, NY, 10018

- Tel: (212) 930-0601

- “Felix Warburg residence” Photograph Album

- Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

- Columbia Univsersity

- 300 Avery Hall

- 1172 Amsterdam Avenue

- M.C. 0301

- New York, NY 10027

- Tel: (212) 854-6199

- Email: avery@library.columbia.edu

- Genie Rice Archive

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

- New York, NY 10075

- Tel: (212) 988-8379

- Email: info@nypap.org

- Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 150 LP-1116, 24 November 1981, 3.

- Ron Chernow, The Warburgs: the 20th-century odyssey of a remarkable Jewish Family (New York: Random House, 1993); Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009, 315).

- Edward M.M. Warburg, ‘1109’, the Warburg House: an informal guided tour (New York: Jewish Museum, 1996, c1984, 19).

- Lee E. Cooper, “Warburg Mansion Sold to Provide Site for 18-Story Apartment House on Fifth Ave.,” The New York Times, 24 May 1941.

- “Warburg Mansion Goes to Seminary,” The New York Times, 25 January 1944.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 150 LP-1116, 24 November 1981, 5.

- “Museum to be Renovated,” The New York Times, 26 May 1962; Ada Louise Huxtable, “Design Notebook: A Mansion that Deserves More than Platitudes,” The New York Times, 27 December 1979; Grace Glueck, “A Redesign for Jewish Museum Expansion,” The New York Times, 12 May 1988; Vivian B. Mann, The Jewish Museum, New York (New York: Rizzoli, 1993, 17); Herbert Muschamp, “Review/Architecture; Jewish Museum Renovation: A Celebration of Gothic Style,” The New York Times, 11 June 1993.

- Christopher Gray, “Streetscapes: The Felix Warburg Mansion; A Window to the Past in the Present,” The New York Times, 11 August 1991.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission, Designation List 150 LP-1116, 24 November 1981, 1.

- Deirdre Carmody, “Jewish Museum Proposal Revives Landmark Issue,” The New York Times, 15 June 1981.

- Maurice Carroll, “Landmark Status Voted for Warburg Mansion,” The New York Times, 25 November 1981.

- Ronald D. Spencer, Phillips G. Smith, Peter E. Truesdale, and Genie Rice. Letter to Miss Ellen Hay, Special Assistant to the Borough President, 12 Dec. 1981.

- Genie Rice, “Petition Signatures,” Letter, 1982.

- Genie Rice, Personal Communication, remembering August Heckscher, former Parks Commissioner under Mayor Lindsay, and Frank Lichtensteiger, “a tireless community activist in helping with the Alliance effort.”

- Clyde Haberman, “Board of Estimate Agrees to Allow a Tower Next to Warburg Mansion,” The New York Times, 2 April 1982.

- Grace Glueck, “A Redesign for Jewish Museum Expansion,” The New York Times, 12 May 1988.

- Herbert Muschamp, “Review/Architecture; Jewish Museum Renovation: A Celebration of Gothic Style,” The New York Times, 11 June 1993.

- Vivian B. Mann, The Jewish Museum, New York (New York: Rizzoli, 1993, 7).

- Genie Rice, “Opportunities and Issues: Landmark Mansions to Community Planning,” Talk delivered at the Cosmopolitan Club, 21 February 1995.