Searching for Jane

November 8, 2017 | By Elizabeth Rohn Jeffe, Vice-Chair

Article from the Fall 2017 Newsletter

Director Matt Tyrnauer’s new film, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, is breathing new life into the story of preservation activist Jane Jacobs, best known for her battles in the 1950s and 1960s with public works builder Robert Moses. The documentary is a theatrical release, premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival and now being viewed at theaters, museums, and other venues worldwide. Aimed at a general audience, it is not intended to be a “niche” film for preservationists and urban planners, but rather a means to reintroduce Jacobs and her insights into the fabric of neighborhood life and the need to preserve it. Her seminal 1961 work on this subject, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, has become a classic.

Tyrnauer, also a contributing editor for Vanity Fair, previously made the documentary Valentino: The Last Emperor, short-listed in 2010 for an Oscar nomination. In a recent interview with the New York Preservation Archive Project, Tyrnauer described how, although he had read Jacobs’s Death and Life only about five years ago, he had been interested in preservation while growing up in Los Angeles. He feels that L.A. commits “everyday transgressions” against its architectural past, with an “amnesiac” approach to its built environment. Tyrnauer recounted how he would pass a lovely Victorian house, see an ugly modern façade on the front, and then walk by the side of the home and see the historic exterior still in place. This tendency to thoughtless destruction of the old made him sensitive to the issue of preservation.

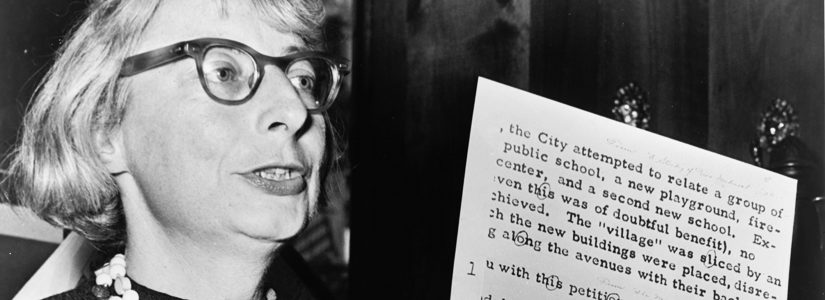

In creating Citizen Jane, Tyrnauer and his creative team faced a monumental amount of archival research, which is of particular interest to those dedicated to saving and using preservation archives. When asked about the importance of this type of research for what Tyrnauer describes as a “character-driven” documentary film (the characters being Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses), Tyrnauer spoke to the magnitude of the task at hand. One of the greatest challenges was finding filmed interviews with Jacobs herself (there is no shortage of available film on Moses). There were a few interviews of Jacobs from the 1960s, but unfortunately, most local radio and television interviews were not preserved. Matt Tyrnauer’s “big find” was a 1970s German documentary, New York: Empire City, featuring a three-hour interview with Jacobs conducted in Toronto, where Jacobs moved after leaving New York. The black-and-white footage of Jane Jacobs speaking that appears in Citizen Jane is footage from this film. Tyrnauer happened upon it while shopping around for imagery and contacted filmmaker Michael Blackwood, who had the master copy. It was actually preferable that it was a film recording, because in the 1970s film could be preserved better than video could. For Tyrnauer, finding this filmed interview of Jacobs was critical because it could balance out the plethora of camera material featuring Robert Moses.

Tyrnauer noted that there are numerous other “wonderful” sources for archival research. Among them are the WPA Film Library and the Library of Congress, the resources of which are in the public domain, as well as the New York City Municipal Archives, which Tyrnauer described as “invaluable.” Interestingly, a great deal of material for the film was made possible by combing through the extensive archives of Robert Moses.

Originally part of the various Authorities that he chaired, such as the Port Authority and the Triborough Bridge Authority, the Moses archival materials became part of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Its warehouse is a trove of research materials for those seeking to understand Moses and the battles in which he was engaged. Of great importance to the impact of Citizen Jane is the fact that these archives contain films that Moses himself made, so Citizen Jane most likely includes some footage never before seen publicly.

For Tyrnauer, the “rarest footage” in Citizen Jane relates to the three epic battles that Jacobs fought with Robert Moses: the fight against extending Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park, saving the West Village from the destructive effects of urban renewal, and blocking the creation of the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway that would have cut through SoHo and Little Italy. Tyrnauer wanted images of protests, public hearings, and the like on film, but these were difficult to source. The first of these battles was not widely covered by the media, and the second received more print attention than film focus, but the fight against the Lower Manhattan Expressway had the most coverage. For that one, Tyrnauer found a local TV shoot of protests on Little Italy’s Broome Street that featured Jacobs and a neighborhood priest speaking out in favor of saving the endangered neighborhood. There is also footage of ordinary residents asking why their homes must be destroyed. As it appears in Citizen Jane, this segment is particularly effective and ends with footage of Mayor Robert Wagner announcing that the Board of Estimate would not fund the project—a victory for Jacobs and the activists with whom she worked. Tyrnauer also found it challenging to locate visual images of the East Harlem area where a large housing project went up in the 1960s but did manage to do so, and this footage also appears in Citizen Jane to great effect.

When asked more specific questions about the making of the film itself, Tyrnauer offered many insights. One issue in making a “character-driven” documentary is how to deal fairly with both characters, in this case, how to create a balanced portrayal of Jacobs without making Moses one-sided. Tyrnauer’s response reflected what he considers to be Moses’s historical trajectory. Before World War II, Moses was a progressive in the classic mold, trying to create better lives for people by designing recreational areas for the masses to enjoy and other such projects. After the war, Moses emerged as a different man, with a different attitude, who became part of a large bureaucracy devoted to public works projects that often did not reflect the real needs of the people whose lives the projects would affect. Roads and public housing projects, for example, however intrusive or destructive to the people in their path, were funded by the government, and aided real estate developers, labor unions, and the construction, automobile, and steel industries. Moses became part of an industrial complex that created its own economic engine for tearing down and building, with the genuine needs of citizens often disregarded.

As for choosing the actors to voice Jacobs and Moses, Tyrnauer said that Marisa Tomei approached him when he was making Citizen Jane because Tomei’s father had long been a Greenwich Village preservation activist and she wanted to help. Hence, she voices Jacobs’s part in the film in those segments where Jacobs herself is not appearing in an interview. As for Robert Moses, Tyrnauer wanted to find an actor who could speak with a “brooding darkness” and found the right actor in Vincent D’Onofrio. Another component of Citizen Jane is its interviewees, a roster that ranges from architectural critic Paul Goldberger to former Mayor Ed Koch. Tyrnauer said that he wanted everyone who spoke in the film about Jacobs to be well-qualified to do so, and as a result, those who appear on camera are activists, biographers, and scholars. The fact that Ed Koch began his career in the Village as an activist appealed to Tyrnauer. Fortunately, Tyrnauer was able to capture Koch’s comments in the last interview that he gave before his death in 2013.

When asked how long his research for Citizen Jane took, Tyrnauer replied, “Years!” He uses professional film archivists to assist him and commented that the archivists in the various repositories that he visited were all extremely helpful. Explaining that documentary film is a “pastiche” of archival materials intermixed with interviews, Tyrnauer noted that Citizen Jane is unusual in that a full 70% of the material used is archival, a much higher percentage than usual.

Preservationists are applauding Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, and not surprisingly so. The Archive Project’s screening of the film in April with an ensuing discussion with Tyrnauer was a great success. As Tyrnauer put it, Jacobs spoke “power to truth,” and he wanted to create a documentary celebrating that idea. But for those involved in preservation battles today, the creation of the film also bears witness to the critical importance of preserving the story of preservation so that it can be celebrated and learned from. With regard to the importance of having key archival resources at hand in order to create Citizen Jane, Tyrnauer said, “The archival images of the lost city are full of pathos. How can you look at pre-war images of Penn Station, or the lively streets of Harlem or the South Bronx and not feel the tragic loss of these cityscapes? We need these images in order to understand the magnitude and beauty of what was lost. It’s one thing to read Jacobs’s powerful words about what she calls ‘the old city.’ No one wrote about what was needlessly destroyed more compellingly than she did. But we need the visuals, too, in order to bring us there, and help us make good decisions about cities of the future.”