With Brush and Pen Building a Case for Preservation Through Art

By Pamela Wong

While smartphones make it easy for anyone to photograph remarkable scenes in New York City, many artists—past and present—have picked up a pen or brush instead to document the city’s sites and landmarks.Pro led here are five New Yorkers whose perspectives on historic preservation

through art demonstrate how this form of documentation is actually part of the broader preservation movement. Artistic representations of the historic built environment can convey in a unique way why a structure or streetscape is worthy of preservation efforts, thereby helping to build constituencies engaged in preservation advocacy.

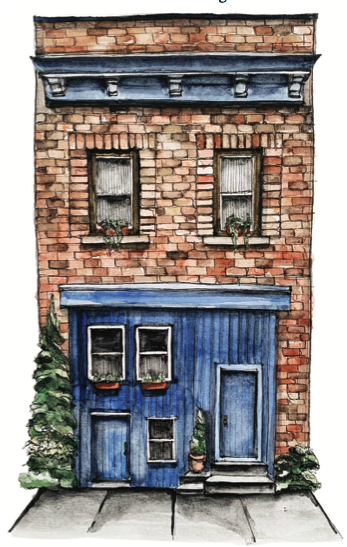

Diane Hu, “Park Slope, 9th Street.” Watercolor on paper. Rendering of the 1856-57 William B. Cronyn House at 271 9th Street in Park Slope, Brooklyn, designated an individual city landmark in 1978 | Courtesy of @dianejosephinehu

Finding Real Value in the Village

Artist Kazuya Morimoto has painted lushly- hued watercolors of Greenwich Village for 13 years, meticulously portraying the area’s architecture, streets, and denizens. He has been “archiving old shop fronts and capturing the moments of local scenes before they change and lose their current quality” as he puts it. Some popular neighborhood haunts he has immortalized include Café Cluny, Cherry Lane eater, Cornelia Street Café, Je erson Market Library, and Village Cigars.

Originally from Japan, Morimoto lived in the Upper West Side and Williamsburg before settling in the Village three years ago. He has painted scenes of the Lower East Side and Soho along with his own picturesque Village neighborhood. “It’s a beautiful part of the city,” he said, pointing out the “old architecture,” “tree-lined streets” and sense of community created by the “very friendly” locals and their dogs. Morimoto also references Greenwich Village’s creative past, observing that “It’s an important part of the history of New York City. Many artists used to live [here] and created art, music, and literature. [It was the] original bohemian neighborhood. Unfortunately, not much art is going on in this area since its gentrification. The artists were pushed away but it’s still a nice neighborhood.”

Kazuya Morimoto, “West Village,” Watercolor on paper. | Courtesy of @kazuyamorimoto

Morimoto stresses the importance of historic preservation and insists, “If they start building glass buildings in Greenwich Village and the West Village, [there will be] no reason for me to stay and paint this neighborhood. It’s important to pass the legacy of history to the next generation.” The artist travels to Europe each summer to paint old cities and villages. “People in Europe know it’s important to preserve historical monuments and environment,” he said.

“Humanity has arrived today through various experiences. Many towns and villages disappeared due to wars or natural disasters…. It is impermissible for our generation to end what our ancestors have protected and nurtured.”

A Painter and Preservationist

Morimoto is not alone in his desire to save the character of Greenwich Village. The late Whitney North Seymour, Jr. (1923- 2019) also championed the neighborhood in the middle of the last century as a leader in the historic preservation movement. A member of the Greenwich Village Association, a New York State Senator, and a United States Attorney, Seymour was also an avid painter.

After being appointed Chairman of the Committee of Preservation of Historic Courthouses in 1957, Seymour spent that summer traveling across New York State to paint pre-1900 courthouses, bringing awareness to the landmark structures and saving them from demolition. In 1956 he painted Pennsylvania Station, New York—the railway station built in 1910. He documented the beauty of the Beaux-Arts McKim, Meade, & White masterpiece before it was demolished in the 1960s to make way for today’s Madison Square Garden. Seymour also aided the Municipal Art Society’s efforts to support the establishment of the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1964 and played an important role in the getting the Landmarks Law passed the following year.

Whitney North Seymour, Jr., “Pennsylvania Station,” Oil on canvas. | Courtesy Gabriel North Seymour and Tryntje Van Ness Seymour

Bringing Brownstones to Life in Brooklyn

“ The historic architecture is what makes New York, New York,” insists Brooklyn-based artist Diane Josephine Hu (@dianejosephinehu). “It’s what can turn even a short walk to the bodega into an inspiring revelation.”

When Hu relocated to NYC from Washington state eight years ago, she was instantly awed by the architecture so unlike the “sprawling, cookie-cutter suburban housing developments” she grew up with. “I was immediately struck by the beautiful rows of brownstones sitting behind tree-lined streets,” Hu said of the structures she had previously seen only in movies: “They were even more charming in real-life and I quickly became enamored with all of the different architectural styles and details.” She finds it inspiring that artisans had once “cared enough about their art to create something unique and beautiful for ordinary day-to-day living.”

Diane Hu, “Windsor Terrace. Prospect Park,” Watercolor on paper. | Courtesy of Diane Hu

During her rst years in New York, Hu photographed the buildings and homes that fascinated her. “I especially loved my first Brooklyn brownstone in Carroll Gardens and spent a lot of time capturing the neighboring streets, especially in the historic district throughout the changing seasons,” she recalled. “A couple of years later, I picked up watercolor painting, and found myself really enjoying the process of drawing and painting these brownstones and historic buildings as well. It really makes you notice small details that you would have otherwise missed.”

Hu can be found across Brooklyn sketching and painting en plein air or in coffee shops. “Everything about these old buildings inspires me,” she says. “They are not only visually magnificent and interesting, but also carry so much of New York City’s history.”

The Incomparable Miles Parker

Another artist passionate about preservation, the late Robert Miles Parker (1939-2012), was revered for his lively images of street scenes and buildings across the country. Born in Norfolk, Virginia, Parker grew up in San Diego. In 1969, after discovering that the 1887 Sherman-Gilbert House in his San Diego neighborhood was slated to be razed, Parker founded the Save Our Heritage Organization (SOHO). The group saved the Victorian house and several others from the wrecking ball, restoring and relocating them to the specially created Heritage Park in the city’s Old Town section.

Robert Miles Parker, “ The Polo Store,” 1988, Ink on paper. is image captures the Gertrude Rhinelander Waldo House at 72nd Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan. | Courtesy of Anthony C. Wood

Parker moved to New York City in the mid-1980s where he lived until his

death in 2012. He was often spotted drawing outdoors around his Upper

West Side neighborhood, accompanied by his Norfolk terrier. Published

in 1988, Upper West Side: New York, features 200 of Parker’s illustrations accompanied by his commentary. Parker also drew Broadway theaters,

both inside and out, illustrating the evolution of their designs throughout the years, creating hundreds of pen-and-ink drawings of the majestic

venues. Each drawing gave life and meaning to the structure in his gaze, heightening its value.

Robert Miles Parker’s drawing, “Helen Hayes Theatre” 1997, ink on paper. The marquee, depicting Annie, reminds us that when COVID-19 recedes “the sun will come out tomorrow,” but what it shines on will depend on preservationists remaining vigilant in the months ahead. | Courtesy of Anthony C. Wood

Preservation on a Personal Level

Parker often ran into fellow artist Jill Gill at various preservationist events. “Miles, as he was called, with his thatch of white hair and gaunt face, was really a character,” Gill fondly recalls. “He lived and breathed buildings.”

Born and raised in Manhattan, Gill began documenting the city’s architecture after graduating from the University of Connecticut. “I came home from college in 1954 and lived in my parents’ place on Second Avenue and 22nd Street,” she said. “When I saw the Third Avenue El coming down, I would go out with my Brownie camera and take many, many photographs from various vantage points,” she said. Gill shot the blocks along Second and Third Avenues “that were being destroyed,” documenting her “crumbling world.”

She soon began painting the scenes captured in her pictures. Later, in the 1960s, along with taking photos of sites about to be demolished, she started rescuing architectural relics such as angels, gargoyles, and stained- glass windows. “I didn’t even know about architecture at that point,” she said. “I was fascinated with all the fancy cornices on the Third Avenue tenements and the names on the top of them like ‘Caroline’ or ‘Elite.’” is fascination led her to attend lectures by architectural historian Barry Lewis, inspiring her decades-long pursuit of documenting New York’s disappearing structures.

Though she has painted iconic sites such as the Old Merchant’s House, the no-longer- extant Bonwit Teller, and the Russian Tea Room “before it got glitzed up,” Gill notes that her work focuses not on landmarked structures but records and celebrates “ordinary, vernacular city blocks.” Rich in detail and whimsy, Gill’s watercolor and ink paintings preserve “the buildings that are unremarkable and un-landmarkable that really form the fabric of neighborhoods.”

Jill Gill, “UWS #5,” 2017, Watercolor on paper. Image depicts Broadway at 81st Street | Courtesy of Jill Gill

A series by Gill pays homage to New York City’s old cinemas and theaters “like the wonderful terra cotta-tiled Helen Hayes which used to be on 46th Street.” She recently completed a painting featuring a vacant, “yellowish-brick, twin-peaked, gabled building” on Broadway between 60th and 61st Streets. “It’s one of my favorite quirky buildings and I wanted to preserve that,” she explains. “It’s standing there empty, awaiting demolition.”

In an unpublished book, Townhouse Proud, Gill preserves 100 Manhattan townhouses—some safe in historic districts, others unprotected—in paintings commissioned by their owners accompanied by anecdotes about the homes and their histories. Gill is currently busy completing Building Memories: Lost New York 1954-2019. Scheduled to be released in 2021, the book compiles 100 of her paintings and commentary on lost blocks across seven Manhattan neighborhoods. “It’s totally personal,” Gill says of her work to preserve New York City’s historic architecture. “It became a passion. My people-oriented city is being torn down around me.”

Through the artistic talents and insights of each of the five artists mentioned here, the transmission of history in art serves a double preservation purpose. First, it captures the history the building itself embodies, amplifying the value of the building’s continued existence to the city. Second, it helps to immortalize or at least heighten the importance of an edifice, increasing the likelihood that someone will care enough about it to ensure that it will persist further into the future, whether landmarked or not.

For more:

www.kazuyamorimoto.com/about www.nypap.org/oral-history/whitney-north- seymour-jr/

www.jillgill.net