Jane Jacobs

Also known as Jane Butzner Jacobs

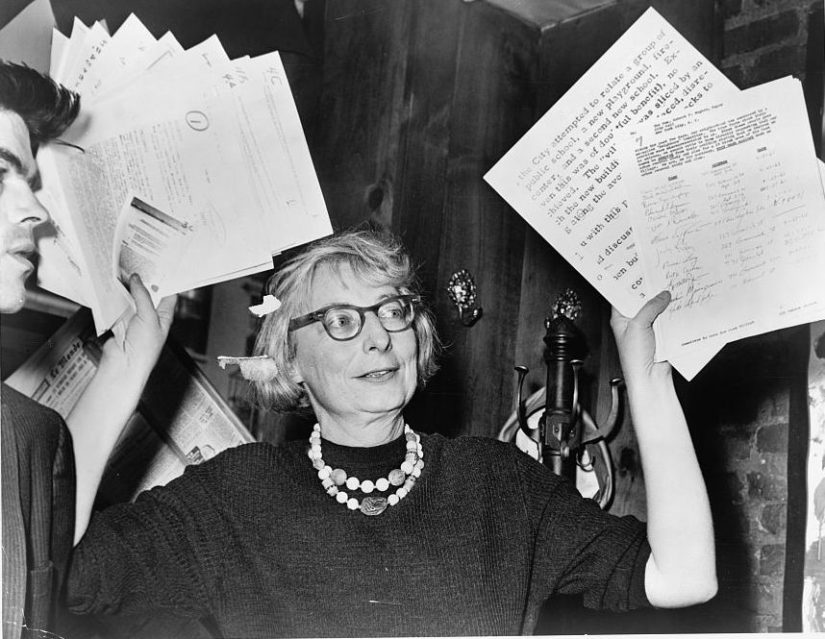

Author and civic activist Jane Jacobs was involved in the efforts to preserve Washington Square Park and Pennsylvania Station.

Jane Jacobs was an author, critic, and ardent civic activist.1 She was born Jane Butzner, on May 4, 1916 to Bess Robinson Butzner and John Decker Butzner, in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Her lifelong career as a writer began in 1934, when she started working at a Scranton newspaper, covering the women’s pages. In 1938, Jacobs moved to New York City and attended Columbia University’s School of General Studies for two years. She took courses in geology, zoology, law, political science, and economics. In 1944, she married Robert Hyde Jacobs, an architect, and they had three children. In 1952, Jacobs accepted a position as the associate editor of Architectural Forum. Jacobs’s expertise was in the subject of school and hospital buildings. She eventually went on to cover stories about architectural planning and rebuilding. In 1958, Jane Jacobs wrote an article for a series that ran in Fortune Magazine entitled, “The Exploding Metropolis.” Her piece gained the attention of the Rockefeller Foundation, which then requested that she continue her writings about the American City.

In 1961, Jacobs published her first book The Death and Life of the Great American Cities, and many publications followed. Her impressive list of published works includes: The Economy of Cities (1969), The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty (1980), Canadian Cities and Sovereignty Association (1980), The Economy of Regions (1983), Cities and Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life (1984), Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics (1992), Toronto: Considering Self- Government (2000), The Nature of Economies (2000) and most recently, Dark Age Ahead, which was published in 2004.2

Though Jane Jacobs never completed college, her theories are noted by sociologists, historians, and urban planners alike. She considered herself an expert on people, and she observed everyday life from her window at 555 Hudson Street. She wrote down descriptions of the interactions that she witnessed. One of her primary contentions was that in an urban setting people are actually safer than in rural areas, because whether amongst “neighbors or strangers,” they are almost never alone.3 In 1969, in opposition to the Vietnam War, Jacobs moved her family from New York’s Greenwich Village to Toronto, Canada. Jacobs took her activist spirit with her wherever she went, and her collection of work covers both the United States and Canada.4 In recognition of her accomplishments, Jacobs was honored with the lifetime achievement award at the Toronto Arts Awards ceremony, in 1986. Additionally, in 1991, in celebration of the 30th anniversary of The Death and Life of Great American Cities’ publication, Toronto declared September 7 to be “Jacobs Day.” Then, in 2000, Jacobs was named an officer of the Order of Canada. She died on April 24, 2006, at the age of 89.5

The New York Times obituary that reported the death of Jane Jacobs praised the visionary nature of her theories:

"Jacobs' enormous achievement was to transcend her own withering critique of 20th-century urban planning and propose radically new principles for rebuilding cities. At a time when both common and inspired wisdom called for bulldozing slums and opening up city space, Ms. Jacobs' prescription was ever more diversity, density and dynamism - in effect, to crowd people and activities together in a jumping, joyous urban jumble.”6

In addition to her vast and influential collection of scholarship on urban planning, Jane Jacobs' contribution to the urban landscapes of both the United States and Canada came also in the form of civic activism. Jacobs's preservation related activities began in New York City. She raised her family in Greenwich Village, and took an active interest in what planners were attempting to do to the neighborhood.7

In the 1950s, urban developer Robert Moses was engaged in a plan to create a roadway through Washington Square Park. Moses's motivation for doing so was to provide a Fifth Avenue address to the buildings that were to be built in a redevelopment area, located south of Washington Square. Jane Jacobs was among those working to oppose the plan. She believed that this roadway was intended to be a "feeder" that would bring traffic through the park to Moses’s planned lower Manhattan Broome Street Expressway project. In 1958 Jane Jacobs, together with several key players such as Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Mead, and Lewis Mumford, formed the Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to Traffic. Jacobs is credited with creating the name for the Committee. Norman Redlich, a Villager and the pro bono council to the Committee recalled that, "Among Jane Jacobs’ many brilliant organizing techniques, one of them was always put what you are trying to achieve in the name of the Committee, because most people will read no further than that. So, it was called the Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to Traffic." It was also Jane Jacobs who strategically realized the need to go directly to the force that possessed the authority to direct the traffic commissioner to place a sign in the middle of the road that would read, "the park is closed." Once she discovered that this power lay with the Board of Estimate, the committee recognized that it would have to employ a highly political strategy. Additionally, fellow activist, Edith Lyons later recalled that it was Jacobs who originally said, "Let’s ask them [Board of Estimate] for a 3 month temporary trial, and I bet you when the trial is over, it will have proved our case and it will never be opened again." Jacobs's prediction was correct and after the three-month trial, the park was never reopened to traffic.8

Jacobs's civic resume extended far beyond the formation of committees. Thanks to the savvy intellect that Jacobs brought to the preservation cause, by the early 1960s her victories included the Washington Square Campaign, the defeat of Moses’s Broome Street Expressway, and successfully keeping urban renewal at bay in the West Village. On August 2, 1962, she marched on the picket line with Ray Rubinow and other leaders of the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York in an attempt to save the original Pennsylvania Station.9 Then, in April of 1968, Jane Jacobs disrupted a public meeting about the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which she vehemently opposed. She was even arrested for her rioting activity. Later, in 1969, when Jacobs relocated her family to Toronto in opposition to the Vietnam War, she continued to engage in battles with urban planners. In an ironic turn of events, soon after her family moved into their new home on Spadina Road, plans were announced for the creation of a Spadina Expressway. Jacobs protested against the construction, and won.10

In 1963, reporter Jane Kramer wrote:

"Jacobs has probably bludgeoned more old songs, rallied more support, fought harder, caused more trouble, and made more enemies than any other American woman since Margaret Sanger."

In preservation lore, she has been described as a "prophet" doing battle with sandaled feet, with her "straight gray hair flying every which way around a sharp quizzical face." Jacobs continued to make lasting contributions to preservation causes until her death in 2006.11

- Jane Jacobs Papers

Archives and Manuscripts Department

John J. Burns Library

Boston College

Chestnut Hill, MA 02467

Oral History with Jane Jacobs- Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

- 232 East 11th Street

New York, NY 10003

Tel: (212) 475-9585

Email: gvshp@gvshp.org

- Oral Histories with Bronson Binger, Anthony Dapolito, Diana Goldstein, Carol Greitzer, and Whitney North Seymour, Jr.

- New York Preservation Archive Project

- 174 East 80th Street

New York, NY 10075

Tel:(212) 988-8379

Email: info@nypap.org

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 184.

- Jane Jacobs Papers.

- Martin Douglas, “Jane Jacobs, Urban Activist is Dead at 89,” The New York Times, 25 April 2006.

- Jane Jacobs Papers.

- Ibid.

- Martin Douglas, “Jane Jacobs, Urban Activist is Dead at 89,” The New York Times, 25 April 2006.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 184.

- Ibid, pages 184-5

- Ibid, page 298.

- Jane Jacobs Papers.

- Anthony C. Wood, Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect A City’s Landmarks (New York: Routledge, 2008), page 298.